The history of science is filled with beautiful hypotheses slain by ugly facts. The tendency of the universe to disregard the professional needs of hard-working scientists is something about which little can be done1. In fact, disproof is a vital and necessary element for scientific progress, no matter how vexing it must have been to Thomas Gold2. However, in that interval between hypothesis and disproof, a sufficiently enticing model can inspire intriguing science fiction stories.

Don’t believe me? Here are five science fiction works based on since-discredited science.

Polywater

Russian scientists suggested that under certain conditions, water could be polymerized. Subsequent experimentation revealed that under certain conditions, water could be contaminated, and the results wildly misinterpreted by Russian scientists.

In the context of the Cold War, the possibility that Russia had access to a novel form of water was sufficient to spark fears about a “polywater gap.” This may have helped inspire Wilson Tucker’s decision to incorporate polywater as a key component to the time machine that plays a central role in Tucker’s The Year of the Quiet Sun(1970), in which a politically, militarily, and racially torn America attempts to secure its destiny by dispatching time travelers to map out the near future. Can America be saved with foreknowledge of its unalterable timeline? The answer not only won a Campbell Memorial Award, but the book also won the award in a year other than that in which The Year of the Quiet Sun was published. Time travel!

Memory RNA

James V. McConnell and others believed they had evidence suggesting that memories could be transferred via RNA from one planarian to another. Attempts to reproduce McConnell’s results failed and the model fell out of favor, as models without support do.

Chemically-transferred memory is a wonderful plot enabler. Thus, it was no surprise to see memory RNA appear over and over. Take for example, Larry Niven’s A World Out of Time (1976), in which the memories of a dead 20th-century American, Jerome Branch Corbell, are transferred into the body of a condemned man. The state that rules the Earth of tomorrow requires a specific mindset for its interstellar starships, which the late Corbell appeared to possess. The state’s assessment is incorrect, as the state realizes once Corbell hijacks his spacecraft for a tour of the distant future.

In fact, A World Out of Time features a number of intriguing but wrong ideas, one of which is…

Bussard Ramjets

Physicist Robert W. Bussard’s 1960 proposal transformed major challenge to relativistic star flight into an asset. He theorized that the thin interstellar medium of hydrogen through which starships would plow could be used as fuel. One could use magnetic fields to divert the hydrogen into a fusion rocket and thus obtain endless fuel and reaction mass. Star farers would not have to worry about being bombarded with relativistic particles and at one gravity forever, the whole galaxy was within reach3!

Too bad that the math does not work and Bussard ramjets, if built, could work far better as brakes than as propulsion systems.

Bussard ramjets were wonderful plot enablers for relativity-curious SF authors, so it was no surprise that ramjets showed up in numerous SF works. Take for example, Lee Killough’s SF procedural The Doppelgänger Gambit (1979), whose plot is kicked off when conniving Jorge Hazlett bilks would-be space colonists by selling them a subpar Bussard Ramjet, with lethal results. Rather than face justice for negligent homicide, Hazlett decides to kill his way to safety with premeditated murder. Of course, it is so hard to stop with just one murder, even in a panopticon state.

Quicksand Moon Dust

Prior to space probes landing on the Moon, the precise nature of the lunar surface was unknown. Among the contending models was Thomas Gold’s4 proposal that the lunar surface could be covered in a layer of fine dust. Depending on the properties and the depth, the layer might act like quicksand5. As it happens, the lunar surface is dusty, but visitors do not have to worry about sinking into it. That is the only good news. Lunar dust is actually much nastier than Gold envisioned. Abrasive lunar dust is a hazard to machines and humans alike.

Arthur C. Clark’s A Fall of Moondust (1961) embraced the most extreme case of Gold’s model. Deep dry dust seas are traversed by lunar boats conveying tourists. A mishap strands a boat deep beneath the lunar surface. Will rescuers locate and retrieve the tourists in time, or will they smother or be boiled in their own body heat6?

The Destruction of Planet V

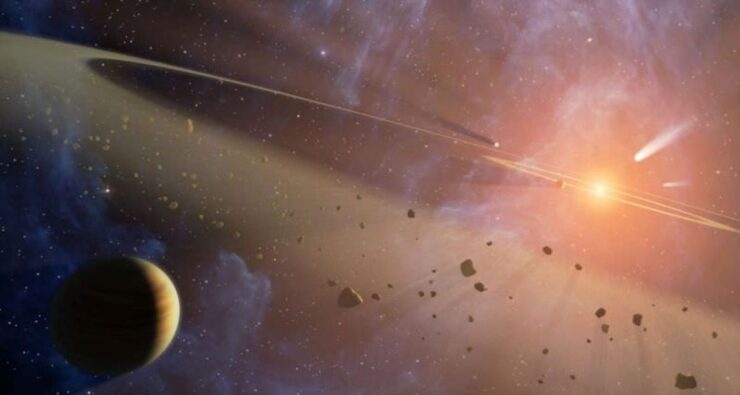

The region between Mars and Jupiter is filled with a myriad of small bodies. That is not controversial. The Belt’s origin, however, has been the subject of various competing theories over the years. In 1972, M. W. Ovenden proposed that the Belt is the remnant of a large planet that exploded about sixteen million years ago. Subsequent evidence… did not support this model* (imagine an emoticon of extreme disappointment inserted here).

[*Note to the editors at Reactor: please use a “this is an extreme understatement” font for “did not support this model.”]

This is not a huge surprise, given that it would take a phenomenal amount of energy to disrupt a 90-Earth-mass planet7, not to mention the total lack of evidence found on Earth for such massive disruption of a nearby world8.

Despite what was even at the time overwhelming reason to be skeptical about Ovenden’s model, there was at least one Disco-era SF novel that incorporated the model in a plot-significant way. In fact, Ovenden’s hypothesis may be the least bonkers thing about Charles Sheffield’s Sight of Proteus (1978), in which advanced biofeedback enables form change, which amounts to shape-shifting. Exposure to fragments of the exploded world prove to have unexpected effects on form change. What these effects are will surprise and delight readers.

Just because a hypothesis may be eventually disproven does not mean it cannot be inspirational before that comes to pass. Indeed, some ideas linger in SF long after they have been discarded by the scientific community. The above is only a small sample of a large field. I may have missed some of your favorite examples. In fact, I hope I have. Please entertain us all with other suggestions in comments below.

- Trust me, you don’t want to go down the “what Lysenko says is science and true” path.

- Trust me, this is very funny, for reasons that will become apparent…

- In the reference frame of the traveler.

- Yes, the same Thomas Gold as in footnote 2. Gold had a talent for being brilliantly wrong in a wide variety of fields. Sometimes he was brilliantly right. Gold correctly identified the source of Jocelyn Bell Burnell’s mysterious repeating signal as a pulsar. His success rate was high enough that even his outré suggestions could not be dismissed out of hand. The fact that there’s never been a Thomas Gold Inspirationally Incorrect Hard Science Fiction anthology is one of SF’s great injustices.

- It is impossible to fully sink in quicksand. I do not recommend quicksand for your body disposal needs.

- The struggle to save the tourists is reminiscent of the efforts to save the Apollo 13 crew, although, since the novel preceded the Apollo mishap, it cannot have been inspired by it.

- Even with perfect efficiency, it would take a full week’s worth of the sun’s output to disrupt the Earth.

- One tends to think of planets as effectively isolated from each other, aside from gravitational perturbation. This is not always the case. The formation of Mercury’s Caloris Planitia about four billion years ago may have deposited up to sixteen million billion tons of debris on Earth.

Asimov’s The Currents of Space (which was later retconned into being part of the timeline between the Robots novels and the Foundation novels) was based on a theory about carbon (and other heavier-than-hydrogen) clouds moving through interstellar space and sometimes causing stellar instability. He admitted to the invalidity of the theory in an afterword appended to later editions.

Quite a number of SF stories became obsolete when it was discovered in the 1960s that Mercury does not have 1:1 spin-orbit resonance but rather 3/2. Asimov complains about it in Asimov’s Mysteries but Niven got burned by the discovery worse. The discovery that Mercury is not tide-locked to the Sun as was thought was made between Niven selling a story dependent on that model and the story’s publication.

Something similar happened to Heinlein: Podkayne of Mars, part of which is set on a habitable Venus, was serialized just after Mariner 2 revealed that Venus was anything but habitable. Presumably POM was submitted to If before Mariner 2 reached Venus.

Heinlein had the “planet 5 done blowed up” theory in at least Stranger in a Strange Land. Possibly In Space Cadet (1948), but my memory is not at all clear.

Both, actually. It might have also been implied in Red Planet, since the Martians there served as the template for Stranger in a Strange Land.

Didn’t Heinlein also use this in Blowups Happen? I seem to remember the physicists thinking the asteroid belt was a result of a power pile explosion.

It’s in The Rolling Stones (1952, I think). Not saying it *isn’t* in the 2 you mention, probably is.

As does James Hogan’s Inherit the Stars, which also includes Velikovskian hijinks that I won’t spoil for new readers.

Ah! Immanuel Velikovsky – I was fascinated as a teenager by his ideas ( a loal public library had a collection of his books). I hope I was aware enough to consider thm more science fiction than fact – but at this distance my memories are clouded…

…or Lysenko (JDN mentions him in his endnotes). Almost singlehandedly destroyed Soviet Agriculture, but I remember readiong, back in the halcyon days of my youth, a doomsday story based on the notion that Lysenko’s pseudoscience was right.

Lysenko’s pseudoscience was actually less insane and less damaging than Mao’s. Mao prevented the use of crop rotation in China for well over a decade on the grounds that plants that grew in soil previously used by the same plants would grow taller because of, I kid you not, class consciousness. This caused an environmental disaster and, well, a famous major famine…

Fortunately, my only exposure to Velikovsky’s theories was Isaac Asimov’s The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction science article that tore them to shreds.

I once came upon a book in my university’s physics library that argued that Venus and Mars had originally formed in each other’s orbits, based on the notion that both planets would be habitable if they were in the opposite orbits and that they must therefore have been cosmically “meant” to go there and gotten swapped around somehow. It was obvious pseudoscience claptrap, and it bewildered me that it had somehow gotten accepted by a reputable university’s physics library.

Meanwhile, in real science we have the Grand Tack, in which Jupiter and Saturn formed at a bit more than half their current distance from the sun, migrated inwards to somewhat outside Earth’s orbit, fixing problems with the formation of Mars, the asteroid belt, and Earth in the process, then migrated back outwards again to more or less where they are now, in only a few million years. This is *not* pseudoscience even though it too seems like planetary billiards, so it’s having holes punched in it and will probably turn out to be wrong in the end :)

It’s not the idea of planets migrating that’s the problem, it’s the issue of why people think they migrated. “Migration explains a lot of the physical evidence we observe” is a good reason to believe that. “Venus and Mars might be habitable in each other’s orbits and my biocentric bias makes me believe that nature intended them to be habitable but something went wrong” is not a good reason.

I believe my intro to Velikovsky was Gardner’s Fads and Fallacies in the Name of Science.

Hogan’s Cradle of Saturn was entirely based on Velikovsky’s theories. Serious Solar-System billiard game craziness.

As I recall, Space Cadet did have the revelation Planet 5 done blowed themselves up real good, as did Between Planets (different version of Planet 5 and different means). Rocketship Galileo explained the Moon’s craters and airlessness with Lunarian atomic war. The moral was that it might be a bad idea to extinct oneself with catastrophic war.

In Space Cadet, “he formed a tentative hypothesis that the planet […] was disrupted by artificial nuclear explosion”. One of the other characters objects to that being possible. I think that it would depend on the level of physics involved. Regular nuclear weapons, I don’t know what mass of weapons would be needed relative to the mass of the planet. But if one could tweak the constants in the nuclear forces so that existing isotopes became less stable? It would probably be unhealthy for us if all of Earth’s uranium, thorium, potassium-40, etc. decayed at once, but my gut feeling is that it wouldn’t bust up the planet.

A few back of the envelope calculations suggest that even a few million years after the Earth formed it would only have led to the magma boiling a bit harder and maybe a bunch of stuff ending up in orbit (adding not terribly much to the mass of the moon). Nowadays things are much less radioactive so there is much less risk (though it might still have interesting effects on vulcanism a few hundred million years later. No sooner than that. Matters move slowly in the deep Earth.)

One fun future apocalypse scenario I’ve run into relates to the ‘giant blobs’, the large low-shear-velocity provinces, which are two huge irregular high-density lumps at roughly equatorial positions on the core-mantle boundary, thousands of miles wide and about a thousand high, probably of planetary mass on their own. These vast monsters beneath our feet are likely connected to every hotspot volcano going, and may have been responsible for starting plate tectonics in the first place; erupted material from such hotspots is isotopically unique and appears never to have been erupted in the history of Earth before — and the blobs might be part or all of the core of Theia, the impactor that formed the Moon.

But that’s not the point here. The blobs have lumps in them that stretch upwards, and some of them are very hot and rise despite their high density, hence their relevance to hotspot volcanoes. Some of these blobs seem to have bigger lumps in them which are possibly also rising. It is possible that such blobs reaching the surface produced the spasmodic intervals of “basaltic province” volcanism in the past which have caused mass extinctions and do things like flood an area larger than North America with basalt to a depth of several kilometres over about a million years.

But… there’s some evidence that there is a very, *very* big lump (maybe 2% the total mass of one of the blobs) on its way upwards under South Africa. If that hits the surface, which it might in about a hundred million years, it might deposit *fifty kilometres of basalt* over much of Africa. So maybe ten times bigger than a basaltic province eruption.

I dunno about you, but I don’t want to be on the planet or breathing its atmosphere when that happens.

And that’s only maybe 2% of the mass of just one blob! Lift the lot — which is probably impossible, they are after all more dense than the surrounding mantle — and life on Earth has had it. Life which might well owe its existence to the tectonic activity induced by the blobs in the first place.

Planet V blowing up was an old, old idea that crops up all the time. Since 1972 seems to be the right date for Ovenden, I’m guessing James is focused on the claim that it was really, really big.

Niven has a long career that has followed in the footsteps of his Mercury problem. It’s astonishing how may times he’s had the props kicked out from under ideas his stories are based on. Makes me wish he’d written a few stories about how impossible cheap, safe fusion and FTL drives are.

Another suggestion for the list, but which violates James’ rule about not repeating books, would be Pohl and Williamson’s Starchild trilogy. That relies heavily on the steady state hypothesis (there’s Thomas Gold again), which was already on its way out as a theory (no matter what Fred Hoyle said) when the first book was serialized. Steady state was probably the least unlikely thing about those books.

Blish’s “Cities in Flight” (tetrology) last novel “Triumpoh of Time” reovolves totally around the Steady State Theory as Amalfi and New Yourl City track down down the spot in the universe where the “ping of spontaneously-created hydrogen comes into existence”. I think it was also some handwavium for Quantum Mechanics, too, though I didn’t know it at the time.,

Niven was following the latest developments in physics and mining them for story ideas, so it’s not surprising that some of them held up better than others.

I found it interesting that he stuck with some of his early discredited ideas (like Mars being inhabited) in his later Known Space stories, rather than decanonizing or correcting them.

Some people seem to have liked an idea that while we live in a Big Bang space, and entropy only increases, this may be only a small bubble inside a larger, perhaps steady-state-ier universe. I don’t know if this is current, and if it means that everything that we can see here still is not steady-state-ish, then I suppose the Big Bang stands.

My first thought on seeing this post’s title was that it could be all about the works of Larry Niven, though as you note James wouldn’t be that repetitive.

Every so often I ponder the gall / hubris / irony of sci-fi stories where the premise relies on characters with access to far-future tech and knowledge being utterly mystified by a physics issue that was readily understood by the Carter presidency. (Serialized TV scripts excepted, for the most part.)

John Varley’s 1979 Titan begins with the discovery in 2025 of a 12th moon of Saturn. Unfortunately for Varley, three Saturnian moons were discovered in 1980. The current count of known Saturnian moons is 146 (not counting ring particles) and 2025 is well off.

Not science fiction, but there was a popular UFO lore about the Dogon tribe in Africa, centered around their knowledge of the “four moons of Jupiter”. Even in the 70s that was dodgy…

Much like dwarf planet, perhaps random small rocks floating around a planet should have a different name (dwarf moon?).

They’re sometimes called moonlets or minor moons/satellites. But it’s an informal usage and there’s no defined size limit.

People with exceptional eyesight can reportedly make out the Galilean moons so it’s not impossible that the Dogon discovered them independently of Galileo. However, what I thought was attributed to the Dogon was knowledge of Sirius B, which is not naked eye visible. Temple proposed the perfectly sensible idea that the Dogon had been contacted by ETs, rather than the rather wild-eyed explanation offered by various extremists that the Dogon might have learned of Sirius B from the European astronomers known to have been in the area in the 1890s.

(There are also suggestions Temple misstated many things about the Dogon, but if you can’t trust popular press pseudoscientists, who can you trust?)

If I had not mentioned Starchild under organ donation, I would have mentioned it here. Steady State is referenced in an even later Pohl story, 1972’s Shaffery Among the Immortals. However, while Shafferty finds Hoyle’s continued Steady State advocacy inspirational, Shafferty is both an aspiring iconoclast and an idiot who doooooms us all, so his respect for Steady State is maybe not intended as a positive thing.

Steady State is (well, sort of) referenced in one of the later Giants novels by Hogan. IIRC, the expansion of the universe causes particles to spontaneously form, so the universe will never actually end.

Of course maximum entropy is a steady state, and is still possible. Although the Big Rip is looking more plausible these days.

Star Trek: The Animated Series‘ “The Magicks of Megas-tu” is predicated on steady-state cosmology, specifically the continuous-creation model positing that there were white holes at the centers of galaxies constantly spewing out new matter. It hasn’t aged well, especially considering all the later productions that have confirmed the Big Bang happened in the Trek universe.

Diane Duane had RNA memory learning as a minor plot point in “Spock’s World”.

John Ford used it in “The Final Reflection”, too.

IIRC, it was an unpleasant method to use, too.

The polywater idea seems to have been the basis of Star Trek‘s “The Naked Time,” where the infection was spread by water that had “somehow… changed to a complex chain of molecules.” James Blish’s adaptation of the episode revised it so that the cause was a water-binding catalyst so strong that it made water bind to itself, “complexing the blood-serum” so it was hard to extract nutrients from it, leading to the crew’s drunken behavior. I’m not sure if he meant that to be the same thing as polywater or not.

My first professional sale, “Aggravated Vehicular Genocide” from the November 1998 Analog, featured a Bussard ramjet starship, but in the expanded novel version Arachne’s Crime I rewrote it into a particle beam-accelerated magnetic sail ship.

Conversely, in my 2010 story “No Dominion,” I acknowledged that memory RNA was a debunked theory (although the story involved the creation of an artificial approximation thereof), but I later heard of some research suggesting there’s some merit to the idea after all: https://christopherlbennett.wordpress.com/2018/05/14/memory-rna-after-all/

“Ice-Nine” in Kurt Vonnegut’s novel Cat’s Cradle (1963), could also have been inspired by the idea of polywater, but I don’t know if the timing is right, as I think the novel predates when polywater became widely known in the USA.

There really is a high-pressure state of ice called Ice IX, one of the nineteen currently known crystalline states of water, though it doesn’t behave the way Vonnegut’s did. I believe that Vonnegut based his version on the real theory of alternate phases of ice, though he took fictional liberties with it. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ice#Phases

Just about all of James Hogan’s later novels were explicitly based upon invalid science that was in line with his libertarian ideology.

At least he was a left-libertarian, the less common variety. I’d say that aside from Voyage from Yesterday, his political views has less direct impact on his fiction than his embrace of completely bonkers pseudoscience like Velikovskyism. This is probably for the best, as Hogan’s political beliefs included holocaust denial.

Speaking of Asimov, his “Fantastic Voyage II: Destination Brain” is an almost-funny example of an author struggling to reconcile “impossible science” with his need to be a hard SF author.

It’s like an apology for getting caught up in writing the novelization of Fantastic Voyage – and even in that one, he supplies a bunch of hand-waving to get around the impossibilities – that the micronauts have smaller atoms, not fewer atoms like mice; their whole space-time size is shrunk. So the Proteus has to have some kind of light-minaturization technology in the windows, to keep the giant radiation outside from looking like radio waves, so to speak.

In the sequel, he tackles a bunch of logical fallout from THAT dodge.

The Good Doctor had needs, and I bet that Hollywood money was awfully sweet.

While not strictly a polymer of water, Ice-9 is modified water central to Kurt Vonnegut’s Cat’s Cradle; to say the least, hilarity ensues.

I don’t know of any SF books that featured it, but the premise of the planet Vulcan (not that one, the other one) is a curious bit of disproved physics. The theory’s biggest proponent was Urbain Le Verrier, who was bugged by how Mercury wobbled like a deadbeat father on Saturday night for no discernible reason. Since he predicted the existence of Neptune through similar means, his endorsement gave the idea some credibility. Ultimately, it was proven to be a result of the curvature of spacetime caused by the Sun’s mass.

I strongly suspect that Star Trek‘s Vulcan was originally meant to be the cis-Mercurian planet Vulcan, given that the original series premise suggested that Spock might be part-Martian (so they were initially thinking in terms of Solar planets), and given that Vulcan wasn’t explicitly established as an extrasolar planet until “Amok Time” in season 2. The existence of Vulcan had been disproven by then, but the idea lingered in science fiction for decades.

By the same token, I suspect the planet Vulcan from Doctor Who‘s “The Power of the Daleks,” a very hot world colonized by humans in the relatively near future, was meant to be Le Verrier’s Vulcan. Two years before that serial, a Doctor Who tie-in book had included Vulcan in its map of the Solar System.

And Doctor Who’s Time Lords disposed of our Planet V in the backstory of “Image of the Fendahl”, or the book at least. Considering what the Fendahl or Fendahls were like, who lived there, it is just as well – except that some of the debris landed here anyway.

They hid the fifth planet in a time loop rather than simply blowing it up. I think much of Doctor Who science is not so much “discredited” as “never meant to be taken seriously in the first place”.

Ross Rocklynne offered at least two different versions of Vulcan, both well after observational astronomy ruled it out and Einstein made the planet unnecessary.

Poul Anderson’s Tau Zero depended on a Russian idea that the universe could collapse into multiple singularities which was disproven by Stephen Hawking in his PhD thesis.

Pre-Mariner observations left open the possibility that Venus had 1:1 spin-orbit resonance [1]. However, I only know of two old time authors who used a tide-locked Venus: Stanley G. Weinbaum and Clark Ashton Smith.

1: Venus’ solar day is 243 Earth days long, while its year is 225 Earth days long. For various reasons Venus spins backwards, which nobody predicted as far as I know.

C.S. Lewis had Ransom saying ‘ “That idea of Schiaparelli’s is all wrong … They have an ordinary day and night there.” ‘ But he did stick with a watery, pleasant-temperature Venus, despite knowing that was wrong.

The Virgin Publishing Doctor Who New Adventures offering “Lucifer Rising” relies on the notion of morphic resonance, as promoted by Rupert Sheldrake, for its plot. I remember being disappointed at that when I originally read it.

Oh, that’s an actual thing? I assumed it was made up for the novel as an excuse for why there were so many humanoids in the Doctor Who universe.

It’s an actual thing, about as wacky as pseudoscience gets. Water has a memory, fine, and can remember things you previously dissolved in it and can act as if the thing is still present even after it’s gone, okay (though clearly something must *wipe* this memory most of the time or the water in my tap would be very strong dino pee). But, um, then Sheldrake started suggesting that this memory could be transmitted between adjacent water tanks that were not otherwise in contact, and then between distant tanks, and then over phone lines, and then over the Internet, with the same amount of compelling evidence for each[1]. Then he *really* went off the rails.

[1] to quote Langford, “I can only declare that the manuscript has so far withstood every test of authenticity to which it has been subjected.”

Wouldn’t the biggie for discredited scientific theories be FTL travel? I know there’s a couple authors out there who seem to still be fans of it…

As I understand, Heinlein’s use of time-dilation in “Time for the Stars” is based on what were some rather vague studies a the time, which have since been overtaken.

No, just the opposite. Writers have always known that FTL was improbable, embracing it as a necessary departure from reality for the sake of the story rather than a realistic likelihood. But if anything, it’s become more plausible over time. Kip Thorne’s research into wormholes for Carl Sagan’s novel Contact revealed there was more merit to the idea than physicists had believed, as did Miguel Alcubierre’s formulation of a “warp bubble” spacetime metric in 1994. Both wormholes and warp metrics have come to be far more actively studied by theoretical physicists in the decades since, and though they’re both still believed to be prohibitively impractical as propulsion methods, they are theoretically sound, and physicists have devised ways to make them orders of magnitude less impractical by finding ways to reduce the energy requirements. There are still obstacles that seem insurmountable, but several obstacles that had been thought insurmountable have already been overcome by the theorists.

No sorry, FTL is not possible. Though people keep desperately trying to find some loophole.( currently involving the latest popular version of tachyons- anyone remember them?)

Look, you can come to with all kinds of results from diddling around with math- if I put i in for the right variable in the rocket equation, I can come up with a rocket that makes fuel. But just because an equation works, doesn’t mean it applies to reality.

The reality is that there is no need for wormholes, or warp bubbles, or for the magic rocks that those theories require. There’s absolutely no sign of such existing in the universe, and they aren’t needed to solve any cosmological questions. No indication that they are anything other than fun intellectual exercises.

The question is not whether it’s “possible.” That’s not the job of science fiction. It’s disingenuous to assume that writers actually believe the things we write about are achievable in real life. We use ideas that serve our stories, plausible or not, and breaks from reality like FTL, universal translators, and the like are often necessary story shortcuts. Asimov used hyperdrives all the time, but he didn’t believe for a moment that they could actually work as he depicted; they were just a necessary story conceit.

The point is simply that the theory has not been “discredited.” The theory we’re talking about here, to be specific, is Einstein’s General Theory of Relativity. Warp drives and wormholes are exotic solutions of the equations of General Relativity, so what’s in question here is not whether the theory is sound, since it’s one of the most solidly verified theories in all of physics, but whether these particular extreme applications of it could ever be practically achievable.

It has always been known that the conditions necessary to achieve those solutions were unlikely to the point of impossibility. As I said, authors use it as a story convenience, not as an expression of actual belief. But Thorne’s and Alcubierre’s work, and the work of dozens of theorists after them, have made them slightly less unlikely by calculating the specifics of how they would work and finding ways to bring them marginally closer to achievability, if you presume a civilization thousands or millions of years more advanced than ours and able to harness immensely greater energies or create types of matter that we have no idea how to create.

To be maximally pedantic, it remains impossible for anything made of matter to equal or exceed the speed of light, always. If you could exceed it, this would be equivalent to a time machine and vacuum fluctuations would repeatedly thread the relevant region and amplify to theoretically unbounded energies — but in practice high enough to disrupt whatever path this was, so that path no longer exists. However, regions of space-time can move relative to other regions at arbitrary speeds, so if you’re inside such a region you can get elsewhere faster than a beam of light could. Combining the two results seems likely to be interesting, since going somewhere superluminally and then turning round and going back again such that you arrive before you left would likely provide just such a path, and if you can follow it, so can vacuum fluctuations, and then all hell breaks loose again. But vacuum fluctuations are a quantum thing and the rest is relativity, so maybe we can escape this when the two are unified! One can hope.

There are countless fun models of the Alcubierre geometry now, mostly with their own hilariously awful side effects. Many models make it impossible to create such a region, or impossible to destroy it, usually both at once, requiring the region to be eternal (just because a solution is possible doesn’t mean there is necessarily any way to turn our current spacetime into it). Other even more fun models have stopping the bubble destroy everything inside it and often more or less everything outside it as well (nice FTL drive that, go to some solar system and oh well nice star you had there, it’s a raging quark-gluon plasma now). There are other even more fun minor engineering difficulties in yet other models, like a region at the leading edge of the bubble which radiates at the Planck temperature, ~1.4×10^32K.

Of course by dint of much research and many, many wonderful models the things are much more practical to construct than they used to be: one model requires only a few milligrams of negative mass, rather than an amount larger than that of the entire visible universe. Not that there is any evidence of negative mass existing, and in that model you do have to squash it into much less than the size of a proton. You can only interact with the outside universe through that tiny constriction, if at all, and quite how you arrange to accelerate and decelerate in that model is, uh, a matter of further study, as is how you make it and how you get out of it again without it turning into a black hole. Making an “FTL drive” that seals you into a nearly-impenetrable jail and then sitting there for years and discovering that you actually went nowhere at all because your velocity relative to your starting point was zero the whole time would be unfortunate.

Fortunately, only scientists and engineers have to worry about what’s actually achievable in real life. SF writers can cherrypick the interesting bits of scientific theories and build stories around them, using just enough of the theory to sound plausible while going mumblemumble about the rest.

As for discredited theories, there’s always Counter Earth, AKA, another Earth sized planet orbiting the Sun opposite the Earth. The only example I have to hand is Gerry and Sylvia Anderson’s Journey to the Far Side of the Sun, AKA Dopplegäner. The Counter Earth is not only a duplicate of Earth, it’s a mirror image of it. (Not at the biological level, otherwise the hero of the story would have died of malnutrition due to the right handed carbohydrates and proteins.)

The concept is featured in The Stranger, a 1973 pilot movie that never got picked up for a series. MST3K fans know it better as Stranded in Space. For more MST3K connections, a Counter Earth was also featured in Gamera vs. Guiron. I believe Gor (from the John Norman novels) is also suppose to be a Counter Earth.

Marvel Comics has a Counter-Earth, a version of which was seen in Guardians of the Galaxy III, although they left out the part where it’s actually opposite Earth in its orbit. The animated series Spider-Man Unlimited from the late ’90s also featured it.

I think there was a counter-Earth planet in the 1940s Superman radio series too. I think there may have been something that claimed Krypton was a counter-Earth planet, but I’m not sure if that was the same thing or something different.

But yeah, I don’t think it was ever actually a scientific theory, just a story conceit.

Golden Age and very early Silver Age Krypton seemed to be based on a mix of ideas, both Planet V and Vulcan. But eventually it was moved to an unspecified different star system.

I looked into this recently, and it was only in the very, very early Golden Age that Krypton was treated as a Solar planet, albeit ambiguously. The 1939 comic strip’s origin story had Jor-L (as it was originally spelled) refer to Earth as a “nearby” planet, yet a later strip shows Kal-L’s capsule nearly running afoul of “the gravity of a giant sun,” the indefinite article implying an interstellar journey. The 1940 radio series apparently treated Krypton as a counter-Earth, at least in its original, bizarre version of the origin story where Kal-El grew from infancy to adulthood en route to Earth (which implies a much longer trip, or a very slow rocket). However, the 1948 Kirk Alyn serial and a 1949 comics origin story both explicitly establish Krypton as a planet in a different star system. So it was decided during the Golden Age.

I doubt that Counter Earth was ever a scientific theory (though it was proposed by a classical Greek philosopher). The geometry is not gravitationally stable.

There’s an infamous science fantasy series set on a counter earth.

Martian canals, a breathable Martian atmosphere, and Mars as a planet in the end stages of desiccation, turn up in a lot of older SF.

Oh, if we get into stories with outdated planetary science, we’ll be here all week. Tidally locked Mercury, swamps and dinosaurs on Venus, canals on Mars, the gas giants having solid surfaces, etc.

Can we still leave a little space for a chorus of The Green Hills of Earth? Just for the sake of old times.

The Enterprise-D has Bussard collectors, but I don’t recall whether they’re meant to be ramjets, or if they’re collecting the hydrogen for some other reason. They even play a major role in one episode, where they’re used to release a bunch of hydrogen so the Enterprise and an alien ship can cause an explosion to free themselves from a Negative Space Wedgie.

The Bussard collectors are based on the ramjet principle, but they’re not a propulsion system in themselves. Rick Sternbach, who worked on TNG as a designer and technical consultant, had worked with Dr. Bussard earlier in his career (Carl Sagan’s Cosmos featured a Sternbach painting and blueprint of a Bussard ramjet starship), so he chose to establish that the red domes on the front of starship nacelles were Bussard collectors for refueling the ship’s deuterium stores from the interstellar medium.

Planet V reminds me that even Isaac Asimov, who probably should have known better, used that concept in the essay he wrote for his Baker Street Irregulars club application, which turned into his short story “The Ultimate Crime.”

Still, I remember that Roger Zelazny PURPOSELY wrote “A Rose for Ecclesiastes” and “The Doors of His Face, the Lamps of His Mouth”, about habitable Mars and Venus, early in his career, even knowing the science was wrong, because he knew he would have only one chance to do it.

Another somewhat older planet-to-asteroids story (possibly skipped due to duplication): Nourse’s Scavengers of Space, in which (IIRC) the cause of the breakup can be related to future-current mining techniques, so the Evil Mining Company(tm) is trying to prevent Our Heroes from producing the evidence (an illustration of the formerly-fifth planet breaking up) that will cause everyone to demand that such mining be shut down.

Speaking of Niven, he wrote and published a story based on quantum black holes during the brief window between Hawking proposing their existence and disproving their existence outside a tiny window of time just after the Big Bang. IIRC he had a bet going with Pournelle over who’d get a quantume black hole story out first, which he technically won. Pournelle never published his.

There was a Star Trek novel where the Enterprise encounters a quantum black hole which causes the ship’s computer to become both sapient and insane. Somehow.

Are you sure? The Enterprise collided with a quantum black hole in the 1986 Trek novel Crisis on Centaurus by Brad Ferguson, but all it did was cripple the ship’s computer and control systems and impede their response to the titular emergency. (And that’s a spoiler, since they didn’t identify the QBH as the cause of the catastrophic failure until the last chapter.)

The only “insane Enterprise computer” novel I can think of offhand was Web of the Romulans from a few years earlier, but that was set right after (or right before?) “Tomorrow is Yesterday” and posited that the Cygnetians’ reprogramming of the computer to report in a flirtatious tone and append “Dear” at the end had actually made the computer fall obsessively in love with Captain Kirk to the point of endangering the mission. It was a really bad novel.

I may have combined the 2 in my memory. It’s been a few decades since I read them. I read every ST novel that came out until sometime in the early 90’s. There were quite a few “read once” and a few “reread many times”.

There was a John Varley where at least one small black hole was intelligent and determined not to be used as a human power source. In a glorious intersection of this essay and the previous one, it was able to escape by recruiting the aid of a clone crew member who was unaware of certain laws pertaining to clones until informed of them by the curiously well-informed black hole.

Much science fiction of the 1920’s – 1940’s involving the concept of homo superior came at a time when eugenics was still considered a a positive, legitimate branch of biology. Since then, when it does appear in SF, it is most often in a negative way.

Sometimes from the same author; Heinlein’s Friday is set a generation or two after “Gulf” and makes a contemptuous reference to the latter’s project of finding and breeding superhumans.

Clarke’s Earthlight also made use of Gold’s “quicksand moon dust” as a plot device to trap two astronomers long enough so they could witness up-close the first and only battle of the Earth-Federation war. Far more plot-centric, though, was the concept that only Earth would have precious metals and rare earths in easy-to-mine depths, while the planets of Mars, Venus, etc. had them trapped at their cores. Since said elements were needed for high technology, this underpinned the whole conflict between Earth and her colonies.

Further, Clarke’s The Songs of Distant Earth also had another theory since disproven – the idea that the Solar Neutrino Problem might be a sign that the sun’s core had shut down, with Clarke extrapolating that the sun would explode as a result. There was at least sufficient time for humanity to seed planets orbiting other stars before this happened.

“Far more plot-centric, though, was the concept that only Earth would have precious metals and rare earths in easy-to-mine depths, while the planets of Mars, Venus, etc. had them trapped at their cores. Since said elements were needed for high technology, this underpinned the whole conflict between Earth and her colonies.”

That’s definitely a discredited idea, because it ignores the fact that the asteroids contain vastly greater abundance of metals and rare earths than you could get if you stripmined the entire crust off the Earth, and they’re far closer to the surface than they are on Earth. Plus you don’t have to lug them out of Earth’s gravity well, so they’re far easier to deliver to space colonies.

No argument here. Although, Earthlight was published in 1955… was anyone thinking about mining the asteroids back then? It’s possible Clarke didn’t even consider the idea at the time.

Asimov’s “Catch That Rabbit” in 1944 was set on an asteroid mining station. Moreover, it treated that setting casually, even incidentally, without any lecture for the audience about the concept of mining asteroids, which suggests it was already an established idea in SF by that point. Wikipedia lists a few other examples from the early ’50s.

Interesting… I’ve seen Isaac Asimov’s robot short story “Reason” (1941) mentioned as almost the introduction of solar power space stations transmitting energy down to Earth by microwave beam. And it’s just to give robots work to do on a space station, with grave consequences if it goes wrong. With that said, the robot brains are powered by positrons. Which do exist but…

Does PSI count? Paranormal powers would fit the category of “disproven by science well before being used in sci fi.”

Hmm, yes and no. It’s true that there was a time when the possibility of paranormal phenomena was investigated seriously by scientists, and when they believed they were getting valid data showing the existence of such phenomena (until the magicians came along and explained how they were being fooled by charlatans or using bad experimental design). However, I would submit that it never reached the point of being an actual theory. A theory is not simply the assertion that something exists; that’s a postulate or an observed result. A theory is a model explaining how something works and/or why it exists, and making predictions that can be tested against new observations or experiments to verify or falsify the theory. As far as I know, nobody ever formulated an actual theory explaining what psychic phenomena supposedly are or how they work. (Some vague handwaves about quantum consciousness, maybe, but they’re more pseudoscience than formal theory.) Insofar as it was ever a science, it was strictly an observational science that never matured to the theoretical level.

Back in the 1980s, Alan Moore took the planarian worm / RNA theory and used it to change Swamp Thing’s origin from being a man who had turned into a muck-monster to being plant life thinking it was once a human being.

Maybe do another one with technological change that didn’t go as anticipated. One of my favorite Heinlein stories, Starman Jones has a starship get lost in space because nobody’s invented the pocket calculator.

Can’t believe nobody remembers James Blish’s Cities in Flight sequence and the Spindizzy.

In one of the books we even get the mathematical equations that can produce a forcefield around New York City so that it can travel to the stars, with all the air held in…

Woh.

Once the field is established it can be maintained by two flashlight batteries…

Double Woh

My as yet unpublished and as yet unwritten sequence The Hardy Annals will feature Spindizzies.

So hands off,

precious, my precious….

Bloody Hobbitses, cuminoverere….

I’m thinking of Poul Anderson’s “Tau Zero”, which was a wonderful novel (and won both Hugo and Nebula) It used a Bussard Ramjet to its ultimate (absurd) conclusion – and Anderson even threw in the collapsing universe (also not a “thing”, apparently).

But he and Larry Niven seemd very enamored of the device.

What about A.E. Smith’s “inertialess drive”?

I don’t think inertialess drive was ever a real-world proposal, just a story conjecture. If anything, it’s based on a proven theory, because we know inertia exists. “Doc” Smith just took the fact that inertia resists acceleration and extrapolated that a futuristic black-box science that could cancel inertia would allow much faster acceleration.