On the outskirts of a village near the ancient Cambodian capital of Longvek, the only sounds are the whir of an electric fan and the hum of insects all around. Suddenly, the silence is broken by the beating of a large drum hanging from an awning. At first, the pounding comes slowly, like a heartbeat. But soon the urgency increases as the rhythm beats faster and faster until suddenly the drummer stops and silence returns to the isolated courtyard. The drummer, clad in white, sits on the ground and prepares a tea set. After a few minutes, villagers, mostly men in white robes, emerge from their homes nearby and start assembling in the courtyard for their weekly prayer.

They are all devotees of Kan Imam San, a sect of Islam practiced almost exclusively by a small number of isolated villages of ethnic Chams in rural Cambodia. They pray only on Fridays, have their own scriptures and writing systems, and do not observe all the rules of Halal. Their behavior often seems to go against what the overwhelming majority of global Muslims would understand as Islam. However, they view themselves as the preservers of the authentic Islam of their ancestors.

Though once almost all of Cambodia’s Chams and Muslims followed Kan Imam San traditions, their numbers have been declining as whole villages have converted to “mainstream” Sunni Islam. Now only 44 mosques, representing less than 10 percent of Cambodia’s total Muslim population, are resisting the temptation of converting and receiving benefits from the international Muslim community.

Chams are a distinct ethnolinguistic group whose ancestors built the Kingdom of Champa in what is now southern Vietnam. For 2,000 years, Cham kingdoms vied for power with their Vietnamese and Khmer neighbors, until Champa was finally destroyed and occupied by Dai Viet in 1832, and most of their population fled into present-day Cambodia. King Ang Duong, who ruled Cambodia from his residence on Mount Oudong, close to the remains of Longvek in Kandal province, allowed the Chams to establish a mosque on the mountain and to settle villages in the area.

To this day, this mosque is considered their sacred site, and the Kan Imam San make a three-day pilgrimage there every year. For the rest of the year, it stands empty and is maintained by volunteer elders. King Ang Duong also gave their spiritual leader, Imam San (after whom the sect is named) a royal grant to use the title “Oknha Khnour,” a combination of the Khmer noble title “Oknha” and the Cham word for “Venerable.” Since then, successive Oknha Khnours have been approved by the community and officially signed into office by the reigning monarch.

While the Kan Imam San used to represent the overwhelming majority of Chams in Cambodia, over the last century their numbers have been in steep decline and most Chams now adhere to mainstream Sunni Islam. The ninth and current Okhna Khnour, Math Sa, sees it as his duty to preserve the sect.

“We lost our land already, so we can’t lose [our identity] as well. It is our pride,” he said during an interview just after the drummed call to prayer at his mosque in Kampong Tralach district, in Kampong Chhnang province. He said that there were now around 30,000 Kan Imam San followers in Cambodia, out of a Cham population of about 300,000. The reason for this, Math Sa said, is that Sunni Muslims receive substantial aid from the global Muslim community, particularly from Malaysia, Indonesia, and Kuwait.

The Indonesian Embassy, for example, says on its website that it has given full scholarships, including living allowance and housing, to 150 graduates of Phnom Penh’s top Sunni school. When asked for comment, an Indonesian Embassy official stated that most of their scholarships are available for all Cambodians regardless of their religious practices, but that some opportunities may only be available for Muslim students if they are related to religious studies. Similar scholarships are offered by Malaysia, Kuwait, and Qatar, but far fewer benefits are extended to the Kan Imam San community. According to several Kan Imam San followers, the only aid they receive from the outside world are occasional gifts of cows from some of the larger mosques in Phnom Penh after Ramadan.

The Oknha Khnour said that his community used to receive aid from the U.S. Embassy, particularly to help them preserve their manuscripts and create materials for teaching the traditional Cham script to their youth.

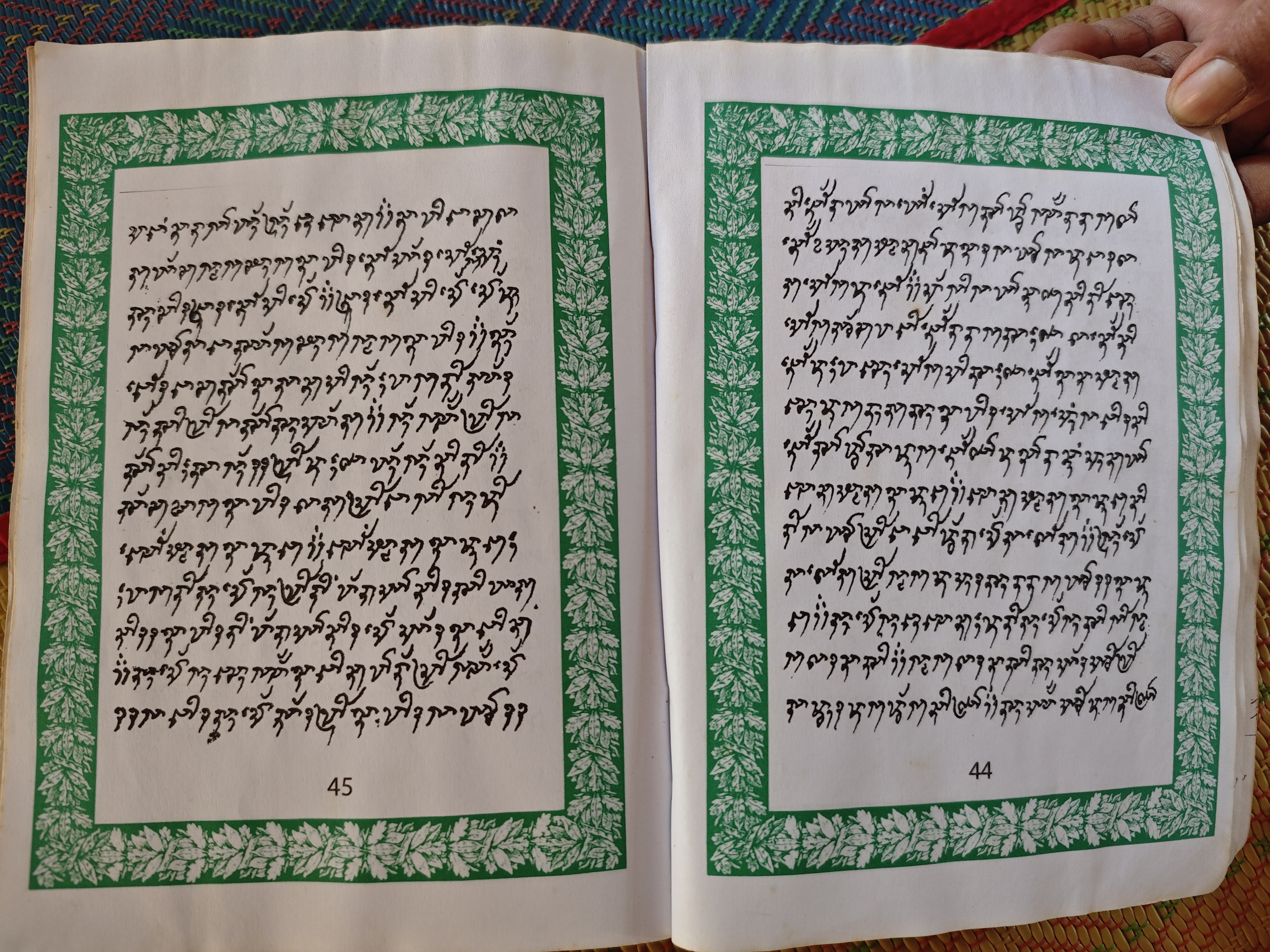

He produced a copy of the Gheet, one of the holy books of the Kan Imam San, which he described as a collection of summaries of sections of the Quran as well as instructions on how to perform rituals. This is the group’s main holy book, alongside 40 kitabs, or treatises, written by Kan Imam San scholars. They also place a lot of importance on a collection of longform poems called Ka Boun, which list the laws and expectations of men and women. This is the Cham version of the Khmer “Chbab Srey” and “Chbab Bros” (Women’s Rules and Men’s Rules), and includes many of the same traditional gender roles as well as additional ones drawn from Islamic tradition.

When presenting the book, Math Sa proudly flipped through the pages, written in swirling Cham script, which he said his ancestors used to painstakingly copy by hand, but which can now be photocopied if they can raise the funds. The edition he showed reporters was printed with help by the U.S. Embassy, which distributed copies to all Kan Imam San mosques in 2011. He told reporters that these books had a big, positive impact on the younger Kan Imam San, as it allowed them to interact with their traditions and made it much easier to help them with their literacy.

The Kan Imam San use three different writing systems in their communities. The Bani script is based on Arabic, but modified to phonetically match the Cham language. This is used for their main holy books. The Cham script is used to write their interpretive texts and cultural books, as well as for signage in their communities. In school, female students focus more on the Cham script, while male students focus more on the Bani script. Finally, Arabic is used for their prayers, as is customary throughout the Muslim world.

The exterior of a Kan Imam San mosque in Tromong Chrom village, Kampong Chhnang, Cambodia, February 23, 2024. Photo by Chantara Tith.

Math Sa said that if he was able to secure more funds from the international community, the Kan Imam San would be able to print more books in the Cham and Bani scripts so that young people would have more materials to learn and practice with. He said that his community receives some support from the Cambodian government, including the salaries of some of the teachers who work at its school. But he lamented the lack of support from other Islamic countries, which goes mostly to Sunnis, and incentivizes members of his congregation to convert.

“As a community leader, I have to do my best to help my community,” he said later via Telegram. “I know that my community is poor, and this poverty makes people less concerned about both religious and social knowledge.”

Math Sa said that by observing Kan Imam San traditions, the community can help to keep it alive for the youth. This is one of the reasons that he says the Kan Imam San put so much emphasis on wearing traditional clothing and performing rituals, as it gets the attention of the youth who naturally want to participate. Their community also created a social media page of Kan Imam San youth activists, which posts short videos of teenagers cleaning up mosques and making jokes in their language, and Instagrammable photos of youths enjoying Cham traditions.

But despite these efforts, their community is threatened with assimilation. Even around his mosque in Kampong Chhnang, which is considered the flagship mosque of the Kan Imam San community, pockets of Kan Imam San Chams are sandwiched between Sunni Cham neighborhoods, which are noticeably more affluent. While the Kan Imam San’s most important mosque and school is a humble building with a distinct Southeast Asian architecture, only a few minutes up the road are far grander mosques and schools built in Arabic style for the Sunni community by Muslim countries.

Though the communities are sometimes separated by as little as a dirt road, they mostly live parallel lives, and are very adamant about which community they are part of. The Sunnis refer to themselves as “the Fives,” in reference to praying five times a day, and refer to the Kan Imam San as “the Sevens” because they pray only once in seven days.

“Here we are Fives, the Sevens are over there, down that market road. You won’t find any Sevens here,” said San Nori, an elderly Cham woman living 600 meters away from the Oknha Knhour mosque. She recounted that some boys from her community had received scholarships to study in Kuwait, and since coming back have taught them new ways to do things instead of their traditional Cham rituals. Since then they have stopped doing the traditional Cham three-day wedding ceremonies, where women hold balls of gold, silver, and platinum in their mouths and eligible bachelors dress as women to escort the groom.

She said that while the Sunni and Kan Imam San communities have friendly relations and sometimes interact at the market, they usually had to live separately because the Kan Imam Sam “do not do things properly.” She said that if a Kan Imam San married a Sunni, they had to convert to Sunnism, but that the other way was not possible. When asked how she would react if one of her children joined the Kan Imam San, she laughed and replied, “That would never happen. It doesn’t make sense! They may as well become Khmer! They don’t even prepare chickens properly!”

“We don’t get a lot of support, but we won’t change.” said Hun Rym, outside his home in Sre Prey, a nearby Kan Imam San village. “We were born as seven-day Iman San, so we won’t change.” Two of his aunts sat beside him and chimed in their agreement. Like all of the women in the community, they wore no head coverings, which they said they only don for the Friday prayer, unlike in the nearby Sunni communities where most women wore head coverings at all times in public. The aunts showed reporters a photo album from Rym’s traditional Cham wedding, and echoed a sentiment shared by many Kan Imam San: that converting to Sunnism was less of a spiritual decision and more of a financial one.

“They joined the Arab side because they have alot of support and donations,” he said. “That’s why they joined.”

The decision to convert to Sunnism can be a personal one, but also often a collective one. Whole communities must choose whether they are registered with the Cambodian Ministry of Cults and Religions as Sunni Muslims or Kan Imam San. Until recently, Kan Imam San villages were dotted all across Cambodia, but the Oknha Khnour said that since the few remaining villages in Kampot switched to Sunnism, they are currently confined to just Kampong Chhnang (16 villages), Pursat (12 villages), and Battambang (16 villages). But this may not accurately reflect how many Kan Imam San practitioners there are.

“Everyone you might ask will say they have joined the Fives,” said Dong Hossein, an Islamic teacher in the village of Tah Vai, “but their actions aren’t so.”

Pages from the Gheet, one of the holy books of the Kan Imam San, written in Western Cham script. Photo by Chantara Tith.

He said that his village officially switched over to Sunni Islam in the year 2000, and soon thereafter received a new mosque and school from Indonesian donors, who also paid for 10 boys in their village to study in a larger Sunni community nearby. Since then, more and more parents have opted to educate their children at the Sunni school. He said that most of the village, except for a few elders worried about their traditions dying out, believed that switching over was a rational choice. However, he said that even today most people do not pray five times a day, and many villagers join their friends and relatives in the Kan Imam San villages to celebrate holidays the traditional way.

“Nobody let go of the Seven way up to today,” he said. “Even though, by name, they go by Sunni, the actions and traditions of Imam San are still adhered to.” The younger generations, however, are studying only the Sunni ways, he added, and soon the traditional Cham writing system will die out in their village as nobody is learning or using it.

A further 20 kilometers deeper into the jungle, far from any paved roads, two small villages of a few hundred families blossom from the narrow dirt path. One village, Srae Sa, follows Sunni Islam, and the other, Tromong Chrom, follows Imam San. Though they are only separated by a few meters, certain differences are striking. Srae Sa has an electronic well pump connected to a foot washing station, and a mosque that appears to have originally been built in the Kan Imam San style but was converted into a Sunni mosque by adding minarets, though this could not be confirmed. Both the mosque and the water pump bear plaques with Malaysian flags. Locals said that their village was Sunni and had always been Sunni, telling reporters emphatically that there were never Kan Imam San in their community.

In the nearby village, however, some residents disputed that statement and said that Srae Sa had converted about 20 years ago.

“The other side put some pressure on us to join them, [saying that] they’ll give us some support,” said Imam Lipsum, the head of Tromong Chrom’s Kan Imam San community. “[But] we have our ancient culture from Champa that we are preserving.”

He said that he had been offered a car, and aid for the community in the form of money and a bigger mosque, if he converted his community to Sunnism. He refused, and instead asked the villagers to try and raise money to improve their community themselves. They were able to expand their mosque, and build their own school, with help from an American family.

“It isn’t easy, but to succeed, we must persevere through all obstacles,” he said. ”It doesn’t matter if we’re rich or poor, as long as we don’t lose [our culture]. When the other side helps us, it is a good deed, so we accept it and offer them the deed, but what I still preserve and protect are our treasures from ancient Champa.”