Social Connectedness 101: Social Connection and Physical Health

Reviewed By Rose Perry, Ph.D.

Illustrated by Dr. Flux

Social connections are vital to our physical health and longevity. Research shows that loneliness and social isolation can increase the risk for disease, illness, and mortality. But supportive social relationships can buffer against these risks and help us live healthier and longer lives.

When it comes to physical health, we are all familiar with the most commonly cited contributing factors: exercise, diet and nutrition, sleep, tobacco use, or alcohol consumption. Although important, these factors focus only on an individual person’s lifestyle and behaviors. More recently, attention has been slowly shifting to social determinants of health, such as social connections and relationships. In fact, in May 2023, The U.S. Surgeon General issued a national advisory calling attention to the “epidemic” of loneliness and social isolation as a public health concern. The significance of social connection has finally come to light following numerous studies demonstrating the profound impact that it has on our health. As the evidence shows, social relationships can “get under the skin” to influence our physical health and even how long we live.

Social Connection and Longevity

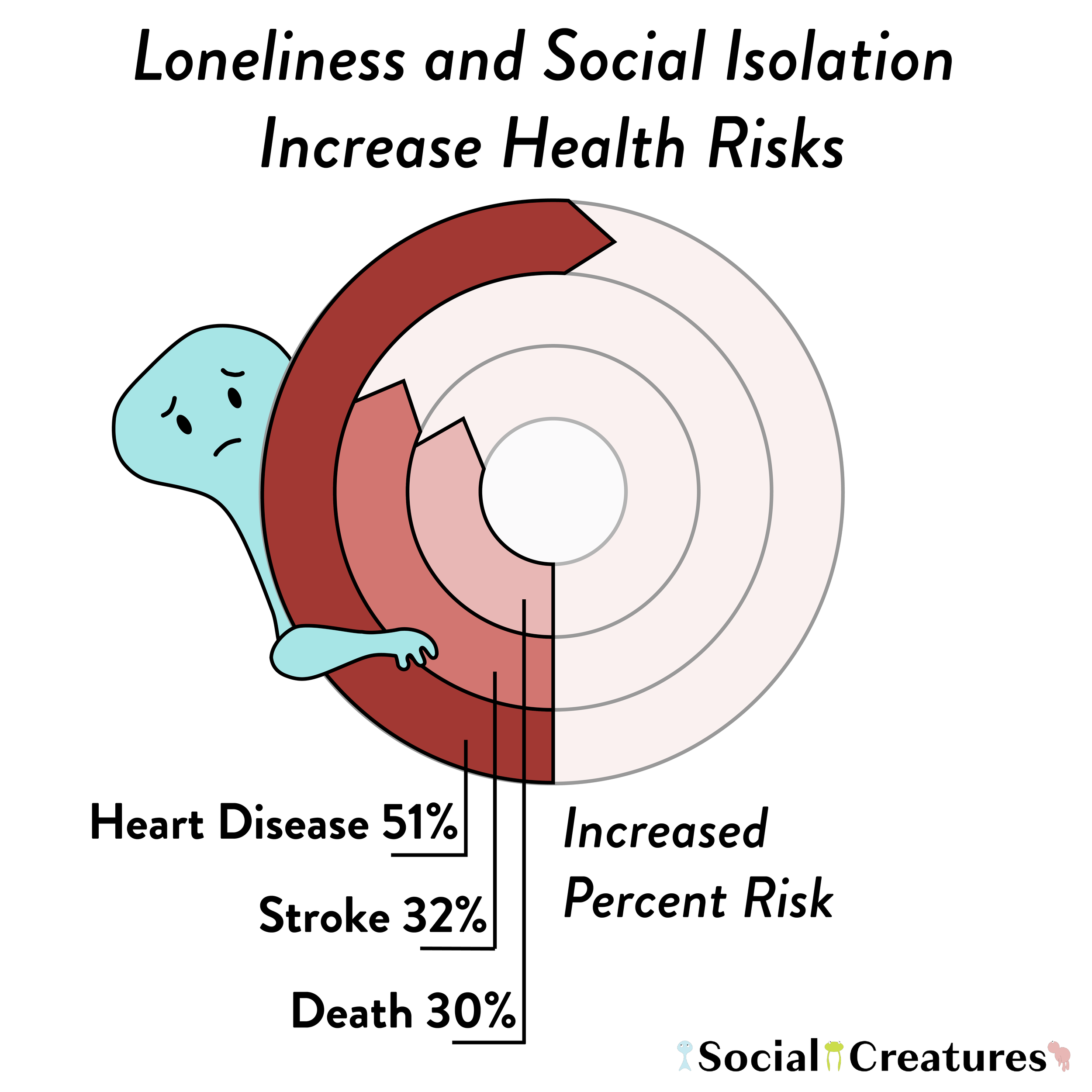

Some of the most compelling evidence on the health effects of social connections concerns mortality. In a 2015 paper, researchers analyzed data from 70 studies that included more than 3.4 million people. They found that loneliness, social isolation, and living alone were associated with a 30% increased risk of death, regardless of the cause [1]. Interestingly, this increased likelihood of death was similar for both objective and subjective measures of isolation and loneliness. This means that it wasn't just the perception of feeling lonely or isolated that mattered, but also the actual experience of being isolated.

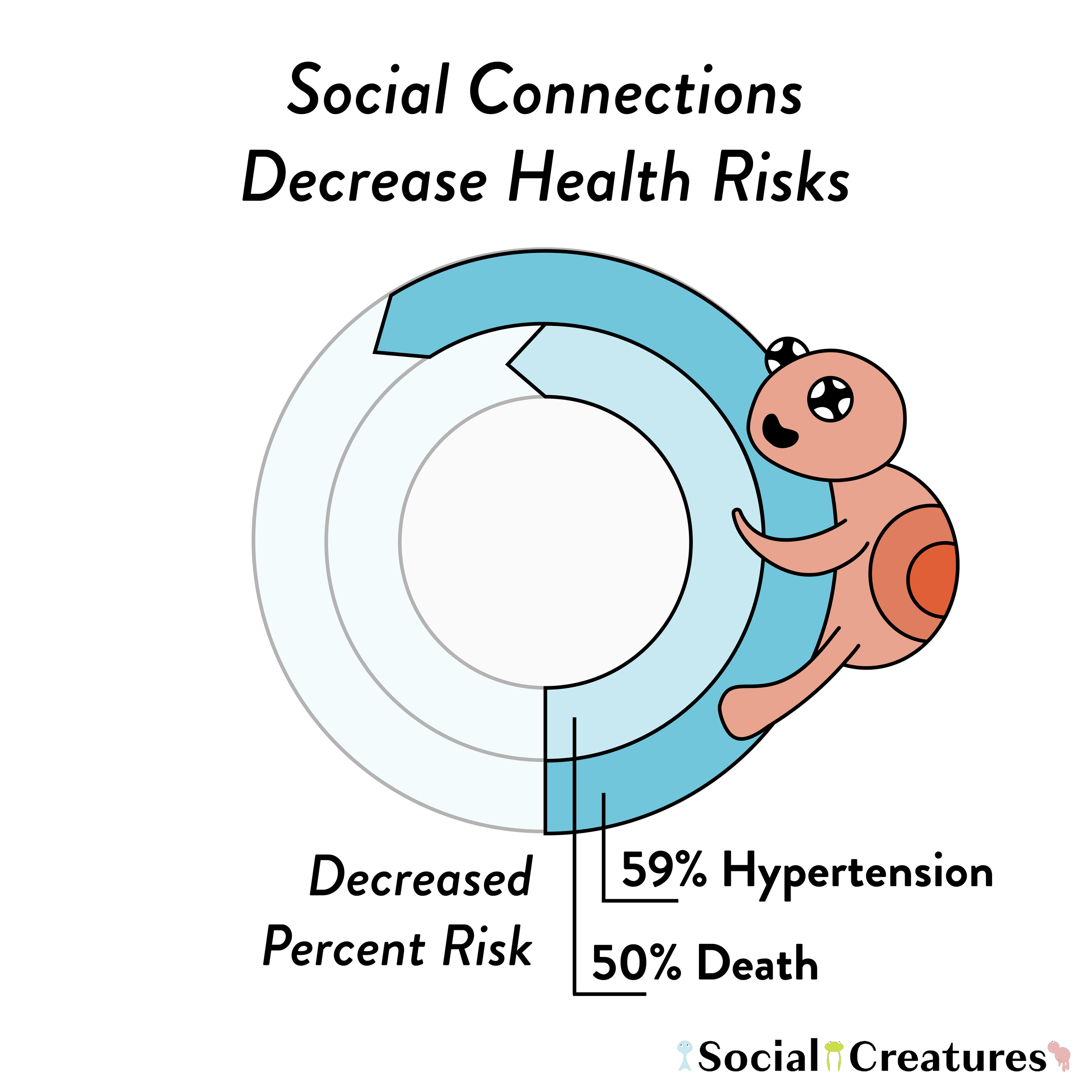

In contrast, being socially connected can help us live longer. Combining findings from 148 different studies and including data on more than 300,000 people, a 2010 analysis found that people with stronger social connections were 50% less likely to die prematurely than people with weaker social connections [2]. Remarkably, the size of this effect was even greater than the impact of many other risk factors for mortality, such as smoking, physical inactivity, excessive drinking, and air pollution. Furthermore, this effect was considerably larger than that of the 2015 analysis, suggesting that the beneficial effects of social connections on mortality outweigh the detrimental effects of social disconnections.

What’s more, both of these analyses took into account the initial health status of participants. This suggests that there is a causal relationship between social connections and mortality. In other words, social connections likely directly influence the risk of death, rather than pre-existing health problems alone being the sole risk factor for mortality.

Why might social connections influence how long we live? One potential explanation is that they drive the development and progression of disease and illness. Indeed, various studies show that loneliness and social isolation are serious risk factors for poor physical health and disease [3,4]. The strongest evidence linking social connection to physical health relates to cardiovascular diseases, including heart disease and stroke.

Social Connection and Cardiovascular Health

Heart disease and stroke are two of the leading causes of death in the U.S., accounting for almost 858,000 deaths in 2021. Research shows that loneliness and social isolation are associated with as much as a 51% increased risk for heart disease [5] and a 32% increase for stroke [6]. Relatedly, one of the leading causes of heart disease and stroke is high blood pressure (hypertension), which is also associated with social relationships. For instance, data from four nationally representative longitudinal studies revealed that socially isolated people were more than twice as likely to develop hypertension—even greater than the risk of diabetes [7]. Loneliness and isolation have also been associated with other conditions that increase the risk of cardiovascular health problems, such as diabetes [8].

On the other hand, studies have found that supportive social relationships can lower the risk and improve outcomes of cardiovascular disease. For instance, people with higher levels of social support or more diverse social networks are less likely to develop heart disease or experience a heart attack or stroke [9,10]. In fact, even having just one supportive relationship can improve recovery from coronary heart disease [9]. Additionally, there is evidence that being more socially connected can reduce the likelihood of developing hypertension by as much as 59% [7].

But how does social connection have such a powerful effect on our physical health?

Social Connection and Stress Physiology

One of the primary ways that social connections influence physical health is through our stress physiology. The body’s response to stress involves activity of the nervous, endocrine, and cardiovascular systems and is characterized by elevated heart rate, blood pressure, and increased levels of the hormone cortisol. And although physiologically responding to stress is important for dealing with challenges when they arise, over time, heightened activity of the stress system can lead to physical wear and tear. More to the point, because persistently elevated levels of physiological stress have been linked to various long-term illnesses, such as cardiovascular disease and diabetes [11], this may be one likely pathway through which social connections impact physical health.

This idea is supported by years of research indicating that loneliness and isolation are associated with increased activation and poor regulation of stress physiology, such as increased blood pressure and alterations of cortisol activity [12, 13]. And, conversely, many studies have shown that high-quality social relationships actually help buffer the physiological response to stress [14,15]. For instance, supportive social relationships can significantly lower blood pressure [16], reduce cardiovascular reactivity to stress [17], and decrease levels of the stress hormone cortisol [18]. In fact, even the mere presence of a supportive person, such as a friend or partner, can buffer the physiological response to a stressful situation [15]. In short, other people can help us regulate our own stress levels, which in turn, can likely improve our overall health and reduce our susceptibility to disease and illness.

Social Connection and the Immune System

Another pathway by which social connections may affect physical health is through our immune system. Inflammation is an immune response that helps us fight off infection and injury. However, like stress, chronically high levels of inflammation have also been associated with worse health outcomes and diseases [19]. Numerous studies have shown that loneliness and social isolation are associated with elevated inflammation [20]. One study in particular found that social isolation increased the odds of having elevated inflammation to the same degree as physical inactivity [7].

In contrast, research also shows that social connections can help buffer against the negative effects of increased inflammation. For instance, one study found that higher levels of social connectedness were associated with as much as a 40% lower risk of elevated inflammation across the lifespan [7]. This means that social connections can likely strengthen our immune systems and protect us from illness.

In fact, research has further shown that social connections may help decrease our chances of contracting the common cold and flu. Interestingly, one study found that people who had fewer than three types of social connections (e.g., parent, friend, spouse, follow employee) were more than four times more likely to develop a cold than people who had at least six connections [21].

Social Connection: A Public Health Priority

All in all, the evidence is clear: social connections help us live healthier and longer lives. Conversely, social disconnection, loneliness, and isolation can seriously jeopardize our physical health and longevity. It should also be noted that although the focus of this article was on the effects of social connection on physical health, there is also substantial evidence linking social connection to mental health outcomes [3,4]—which will be the subject of a future article.

In light of the overwhelming evidence that social relationships are vital to physical health and longevity, it is clear that social connection is a public health issue. Despite this evidence, social connection has still received relatively little attention in public and political domains. The time has come to recognize the significance of social connection to public health and policy, and actively work to create policies and programs to support it. As a first step in this direction, the U.S. Surgeon General has released a national strategy for advancing social connection with recommendations from the national to the individual level. To learn how you can foster social connection to improve your own health or someone else’s, you can explore their recommendations and resources, and support the work of Social Creatures.

In-text References

[1] Holt-Lunstad, J., Smith, T. B., Baker, M., Harris, T., & Stephenson, D. (2015). Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for mortality: A meta-analytic review. Perspectives on Psychological Science : A Journal of the Association for Psychological Science, 10(2), 227–237. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691614568352

[2] Holt-Lunstad, J., Smith, T. B., & Layton, J. B. (2010). Social Relationships and Mortality Risk: A Meta-analytic Review. PLOS Medicine, 7(7), e1000316. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000316

[3] Leigh-Hunt, N., Bagguley, D., Bash, K., Turner, V., Turnbull, S., Valtorta, N., & Caan, W. (2017). An overview of systematic reviews on the public health consequences of social isolation and loneliness. Public Health, 152, 157–171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2017.07.035

[4] Morina, N., Kip, A., Hoppen, T. H., Priebe, S., & Meyer, T. (2021). Potential impact of physical distancing on physical and mental health: A rapid narrative umbrella review of meta-analyses on the link between social connection and health. BMJ Open, 11(3), e042335. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-042335

[5] Steptoe, A., & Kivimäki, M. (2013). Stress and Cardiovascular Disease: An Update on Current Knowledge. Annual Review of Public Health, 34(1), 337–354. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031912-114452

[6] Valtorta, N. K., Kanaan, M., Gilbody, S., Ronzi, S., & Hanratty, B. (2016). Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for coronary heart disease and stroke: Systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal observational studies. Heart, 102(13), 1009–1016. https://doi.org/10.1136/heartjnl-2015-308790

[7] Yang, Y. C., Boen, C., Gerken, K., Li, T., Schorpp, K., & Harris, K. M. (2016). Social relationships and physiological determinants of longevity across the human life span. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 113(3), 578–583. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1511085112

[8] Brinkhues, S., Dukers-Muijrers, N. H. T. M., Hoebe, C. J. P. A., Van Der Kallen, C. J. H., Dagnelie, P. C., Koster, A., Henry, R. M. A., Sep, S. J. S., Schaper, N. C., Stehouwer, C. D. A., Bosma, H., Savelkoul, P. H. M., & Schram, M. T. (2017). Socially isolated individuals are more prone to have newly diagnosed and prevalent type 2 diabetes mellitus—The Maastricht study –. BMC Public Health, 17(1), 955. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-017-4948-6

[9] Czajkowski, S. M., Arteaga, S. S., & Burg, M. M. (2022). Social Support and Cardiovascular Disease. In S. R. Waldstein, W. J. Kop, E. C. Suarez, W. R. Lovallo, & L. I. Katzel (Eds.), Handbook of Cardiovascular Behavioral Medicine (pp. 605–630). Springer New York. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-85960-6_25

[10] Chin, B., & Cohen, S. (2020). Review of the Association Between Number of Social Roles and Cardiovascular Disease: Graded or Threshold Effect? Psychosomatic Medicine, 82(5), 471–486. https://doi.org/10.1097/PSY.0000000000000809

[11] Chrousos G. P. (2009). Stress and disorders of the stress system. Nature reviews. Endocrinology, 5(7), 374–381. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrendo.2009.106

[12] Brown, E. G., Gallagher, S., & Creaven, A.-M. (2018). Loneliness and acute stress reactivity: A systematic review of psychophysiological studies. Psychophysiology, 55(5), e13031. https://doi.org/10.1111/psyp.13031

[13] Cacioppo, J. T., Cacioppo, S., Capitanio, J. P., & Cole, S. W. (2015). The Neuroendocrinology of Social Isolation. Annual Review of Psychology, 66(1), 733–767. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-010814-015240

[14] Coan, JA, Sbarra, DA. (2015). Social baseline theory: the social regulation of risk and effort. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 1:87–91

[15] Ditzen, B., & Heinrichs, M. (2014). Psychobiology of social support: The social dimension of stress buffering. Restorative Neurology and Neuroscience, 32(1), 149–162. https://doi.org/10.3233/RNN-139008

[16] Fortmann, A. L., & Gallo, L. C. (2013). Social Support and Nocturnal Blood Pressure Dipping: A Systematic Review. American Journal of Hypertension, 26(3), 302–310. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajh/hps041

[17] Teoh, A. N., & Hilmert, C. (2018). Social support as a comfort or an encouragement: A systematic review on the contrasting effects of social support on cardiovascular reactivity. British Journal of Health Psychology, 23(4), 1040–1065. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjhp.12337

[18] Gunnar, M. R., & Hostinar, C. E. (2015). The social buffering of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenocortical axis in humans: Developmental and experiential determinants. Social Neuroscience, 10(5), 479–488. https://doi.org/10.1080/17470919.2015.1070747

[19] Furman, D., Campisi, J., Verdin, E., Carrera-Bastos, P., Targ, S., Franceschi, C., Ferrucci, L., Gilroy, D. W., Fasano, A., Miller, G. W., Miller, A. H., Mantovani, A., Weyand, C. M., Barzilai, N., Goronzy, J. J., Rando, T. A., Effros, R. B., Lucia, A., Kleinstreuer, N., & Slavich, G. M. (2019). Chronic inflammation in the etiology of disease across the life span. Nature medicine, 25(12), 1822–1832. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-019-0675-0

[20] Smith, K. J., Gavey, S., RIddell, N. E., Kontari, P., & Victor, C. (2020). The association between loneliness, social isolation and inflammation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 112, 519–541. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2020.02.002

[21] Cohen, S. (2021). Psychosocial Vulnerabilities to Upper Respiratory Infectious Illness: Implications for Susceptibility to Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). Perspectives on Psychological Science, 16(1), 161–174.https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691620942516