I’ve got a special treat for you today. My dear friend Anne R. Allen is here! If you’re not following her blog, you should remedy that immediately. It’s a must-read for all writers.

So okay, what the heck is “Chekhov’s gun?”

It’s a reference to advice the great Russian playwright and short story writer, Anton Chekhov, (1860-1904) gave young writers:

“If in the first act you have hung a pistol on the wall, then in the following one it should be fired. Otherwise don’t put it there.”

In other words, he says we shouldn’t clutter the story with things that have no relevance. If chapter one says your heroine won a bunch of trophies for javelin throwing, which she displays prominently on the wall alongside a javelin once thrown by Uwe Hohn, somebody had better darn well throw a javelin before the story is done.

Setting Details vs. Chekhov’s Gun

Yeah, but what if that javelin is there to show us what her apartment looks like? It’s good to show her décor, because it gives an insight into her character, right?

It depends. Yes, it’s good to use details to set tone and give depth to our characters.

But what’s all important is how you stress those details when you first present them. If there’s a whole page about those javelin throwing trophies, and the characters have a conversation about whether anyone will ever break Uwe Hohn’s throw record of 104.80 meters, you gotta toss some javelins. But if there’s just a cursory mention, “her apartment walls were decorated with an odd assortment of personal trophies and long spears,” then you can leave them on the wall.

In other words, not every lampshade the author mentions has to show up two chapters later on the head of a drunken ex-boyfriend, but you need to be careful how much emphasis you put on that lampshade.

What, No Red Herrings?

Wait just a goldern minute, sez you. I write mysteries! Mysteries need to have irrelevant clues and red herrings. Otherwise the story will be over before chapter seven.

This is true. But mystery writers need to manage their red herrings. If the deceased met his demise via long pointy spear-thing, probably thrown from a considerable distance, then your sleuth is going to look like a very viable suspect to the local constabulary.

But of course she didn’t do it because she’s our hero, so the javelin on the wall and the trophies are red herrings.

But they still need to be “fired.” Maybe not like Chekhov’s gun, but they need to come back into the story and be reckoned with. Like maybe the real killer visited her apartment earlier when delivering pizza, then broke in to “borrow” the Hwe Hohn javelin, but he couldn’t get it into his Kia, so in the end he used a shorter, more modern javelin…

Chekhov’s Gun and Subplots

I’ve been running into this problem in a lot of fiction lately: I find myself flipping through whole chapters that have nothing to do with the main story. That’s because the subplot isn’t hooked in with the main plot. It’s just hanging there, not furthering the action.

The subplot becomes the unfired Chekhov’s gun.

For instance, one mystery had the protagonist go through endless chapters of police academy training after the discovery of the body. The mysterious murder wasn’t even mentioned for a good six chapters. I kept trying to figure out how her crush on a fellow aspiring policeperson was going to solve the mystery.

I finally realized it wasn’t. None of the romance stuff had to do with the mystery. When I finally flipped through to a place where the main plot resumed, the hot fellow student didn’t even make an appearance. He’d already gone off with a hotter fellow recruit.

It’s fine to have a romance subplot in a mystery — in fact, that’s my favorite kind. But the romance has to take place while some mystery-solving is going on.

But if that romance doesn’t trigger a new plot twist or reveal a clue, then it’s an unfired gun on the wall. It’s just hanging there, annoying your reader, who expects it to be relevant.

Naming a Character Creates a Chekhov’s Gun.

Another “unfired Chekhov’s gun” situation often comes up with the introduction of minor characters and, um, “spear-carriers.”

You don’t want to introduce the pizza delivery guy by telling us how he got the nickname “Spear” followed by two paragraphs about his javelin-throwing expertise — unless he’s going to reappear later in the story. And he’d better be doing something more javelin-related than delivering another pie with extra pepperoni.

This is a common problem with newbie fiction. In creative writing courses we’re taught to make every character vivid and alive. So every time you introduce a new character, no matter how minor, you want to make them memorable. You want to give them names and create great backstories for them.

Don’t give into the urge, no matter what the creative writing teacher in your head is saying.

If the character is not going to reappear, or be involved with the plot or subplot, don’t give him a name. Just call him “the pizza guy” or “the Uber driver” or “the barista.”

A named character becomes a Chekhov’s gun. The reader will expect that character to come back and do something related to the plot.

Beware Research-itis

A lot of unfired guns come from what I call research-itis. That’s when the author did a heckuva lot of research and goldernit, they’re going to tell you every single fact they dug up.

You’ll get three chapters on the historical significance of the javelin in Olympic competitions, going back to ancient Greece. And the popularity of depictions of javelin throwers in Hellenistic art. And how both Zeus and Poseidon are depicted throwing their thunderbolts and tridents like javelins…

None of which has anything to do with the dead guy in the back yard with the big pointy spear in his back.

If the reader doesn’t need to know it to solve the mystery and it’s not a red herring, keep it to yourself.

Although a lot of that research will come in very handy for blogposts and newsletters when you’re marketing the book, so don’t delete any of those research notes!

Beta Readers and Editors Can Take Chekhov’s Gun Off Your Wall

It’s tough to weed out all those unfired guns in your own work.

You’re sure you absolutely need to tell us that our heroine won those trophies when she was on her college javelin team where her nemesis, Rosalie Rich, once stole her glasses before a meet…and she found out she could throw better without them and didn’t need glasses after all, which was great because her glasses made her look dorky and after she stopped wearing them, Lance Spears noticed her for the first time. He turned out to be a creep, but…

Your editor will disagree. And eventually you will thank her for it.

So will your readers.

Have you ever left a Chekhov’s gun on the wall? Are you annoyed when you find them in published books? What’s the worst Chekhov’s gun mistake you’ve found in fiction?

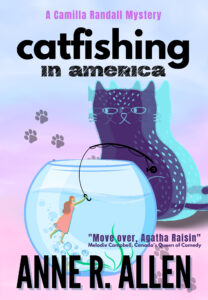

Anne R. Allen is a popular blogger and the author of the bestselling Camilla Randall Mysteries as well as the Boomer Women Trilogy and the anthology Why Grandma Bought that Car (Kotu Beach Press.) Her most recent mystery is Catfishing in America (Thalia Press) a comic look at romance scams. Her mystery The Gatsby Game is being published in French at the end of this month. Anne’s nonfiction guide, The Author Blog: Easy Blogging for Busy Authors, is an Amazon #1 bestseller that was named one of the 101 Best Blogging Books of All Time by Book Authority. She’s also the co-author, with Catherine Ryan Hyde, of the writer’s guide How to Be a Writer in the E-Age. She blogs with NYT million-copy seller, Ruth Harris, at “Anne R. Allen’s Blog…with Ruth Harris.” You can find them at annerallen.com.

Anne R. Allen is a popular blogger and the author of the bestselling Camilla Randall Mysteries as well as the Boomer Women Trilogy and the anthology Why Grandma Bought that Car (Kotu Beach Press.) Her most recent mystery is Catfishing in America (Thalia Press) a comic look at romance scams. Her mystery The Gatsby Game is being published in French at the end of this month. Anne’s nonfiction guide, The Author Blog: Easy Blogging for Busy Authors, is an Amazon #1 bestseller that was named one of the 101 Best Blogging Books of All Time by Book Authority. She’s also the co-author, with Catherine Ryan Hyde, of the writer’s guide How to Be a Writer in the E-Age. She blogs with NYT million-copy seller, Ruth Harris, at “Anne R. Allen’s Blog…with Ruth Harris.” You can find them at annerallen.com.

Don’t miss Anne’s new release! CATFISHING IN AMERICA is a mashup of mystery, romcom, and satire.

“…somebody had better darn well throw a javelin before the story is done.”

Or at least get hit with the base of a trophy. 🙂

Haha! 😀

True. A trophy would do in a pinch!

Great post, Sue. I have a bunch of guns hanging around in the wip, and I’m dealing with deciding how many of them will still be there when the book ends.

Are they laying the groundwork for things that might happen in the next book? Will there even be a next book?

This is where I add a sticky note to my board to remind me to follow up with details, and if I don’t, then why are they there?

Precisely, Terry. I use the comments in Word. 😉

Terry–Thanks for bringing that up. I hadn’t thought about “guns” in a series, but yes, you might save them for the next book.

Great post and hits home because I’m in the midst of revisions on a co-authored project and we’re going through this right now. I don’t know how much of an issue it is for authors who plot their mysteries beforehand, but when writing seat of the pants, you throw in things that feel like they’re going to be great for the mystery but when you do your first re-read and start making edits, you realize, “Oh wait. We introduced this character or scenario in this early chapter but we never once followed it up. What’s it doing here then?” Part of the ‘fun’ of revision work. 😎

The other thorny thing to me is character names–I totally get not saying much about them if you don’t intend to use them, but the flip side is what if you are writing a mystery series set in a small town–you want to begin building community from the beginning. Unnamed characters are great for some spots in a story, but sometimes it just doesn’t feel right not to give them a name, even if briefly mentioned. On the other hand, in any given novel, a lot of characters are introduced and you don’t want to make it hard for the reader to keep the names straight.

I suspect I’m going to have to learn through trial and error. Hopefully betas will pick up on problem areas. My encouragement is that in the grand scheme of things, I haven’t noticed this much in the books that I have read, because no examples come to mind. So eventually authors get the hang of it. 😎

Introducing lots of characters is a problem, Brenda. When characters have names, readers feel they’re important. I may write “The tall dude from the coffee shop” or whatever. That way, the reader knows he’s not important and only part of the world building. There are a ton of other ways of dealing with one-off characters. It might make a good future post.

In the meantime, I’m sure Anne’s covered the topic at least once on her blog. Check the archives (linked in the post).

Brenda–Any named character in a village mystery will be a suspect or secondary character. You do want secondary characters, but not too many. Here’s my post on what to do if you have too many characters. https://annerallen.com/2020/05/too-many-characters/

Thanks. Look forward to checking out the link and pondering edits.

I’vee read somewhere that if you mention something three times in the first act, the reader expects it to matter to the story.

Huh. Never heard that, Patricia. Makes sense.

I’ve never heard of it either, but it works as corollary to the Chekhov’s Gun rule.

Welcome to TKZ, Anne! Thanks for a great post and thanks to Sue for inviting you.

I’m impressed that Anne knows Uwe Hohn’s javelin throw record of 104.80 meters. Are you a sports fan? A competitor?

Chekhov’s gun is such an important principle for mystery writers. Readers who try to solve the mystery along with the detective are always alert to things like the javelin hanging on the wall, and I think it gives them a sense of pleasure when it shows up later. “Oh, so that’s how it fits in.”

I agree, Kay.

Anne should be along shortly. She’s on California time. 😀

Kay–Haha! No, I’ve never thrown a javelin. But I’m a big fan of Google. 🙂 Yes, what we’re going for as writers is that careful reader’s “Ah-ha” moment when it all fits together.

You can also do a Chekhov’s gun in reverse, which is very handy. For example, at the end of the book you may have a loose thread to tie up. But how? One way is to create a minor character to show up with the resolution or explanation. Then you go back and plant that character in an earlier scene.

I didn’t realize it had a name, but I’ve done it. LOL Thanks, Jim!

Jim–The elves ate my last response. I’m hoping this will be allowed. I never gave it that name, but I do it all the time. I’ve read that Agatha Christie did, too. She never knew the culprit until the end. Then she’d go back and plant clues.

Wow, this is the best explanation of Chekov’s gun I’ve ever read. Clears up so much.

I don’t have many “guns” precisely because I don’t focus on objects or wall decoration. They go in last. But in an early WIP, I did have a fantastic collection of magical fountains that I spent a few paragraphs on while my MC was cleaning them. They were meant to figure greatly in the climax, but in a writing workshop, the workshop leader went on and on about how I just wasted a bunch of words on something unimportant. These writing teachers see whatever they want.

Also, this isn’t exactly a chekov’s gun, but a book I read once said at the beginning that it was difficlut to get rid of said problem because it helped keep the environment in balance. At the end, the characters completely obliterated said problem with no mention of how they will keep environment in balance without it. Never read that author again.

Anne has such a great teaching style, doesn’t she? Your writing teacher should’ve asked how those “guns” figured into the plot, rather than telling you to eliminate them.

azali–This is the trouble with critique groups and workshops that critique a work in progress. I had the exact thing happen in a critique group this week. A person complained about “filler” in a person’s conversation. I wasn’t supposed to speak, but I had to say, “they’re called ‘clues’.” 🙂

Sue, thanks for inviting Anne! Anne, thanks for your always practical, down-to-earth advice. Posts like this are why I started following your blog umpty years ago. Love how your sense of humor comes through with your advice.

I recently beta-read a cozy that takes place in a world the author has built over a number of books. There are continuing minor characters named as community members. About a third of the way into the book, the main mystery got lost for a number of chapters as subplots about these minor characters occupied the hero’s attention. The subplots were wrapped up by the end but weren’t relevant to the main mystery.

I suggested the author salt in mentions of the main mystery during that long detour.

My question: is that much meandering acceptable in cozies?

I agree about Anne’s advice, Debbie. She’s awesome. 🙂

A good cozy doesn’t meander. But in a series, when you’ve got attached to all the characters, it can be tempting to go off on a tangent. I love it when those tangents actually lead to the mystery solution, but sometimes they don’t. Then it’s kind of boring.

Great post, Sue and Anne. Your discussion on characters and subplots, and how much is too much or too little, was very helpful. Thanks!

In my response to Brenda? Glad you found it useful, Steve!

Anne has such a great teaching style. Love her blog.

Steve-It does depend on your characters and your style, of course, but we do want to keep our focus on solving the mystery.

Isn’t Anne’s amusing post style great? Thanks Anne and Sue.

BTW, I introduce spears in my Neanderthal series, and, boy, do they use them!

Hahaha. I bet you did, Harald!

Yes, I agree about Anne. Love her style. 🙂

Harald–Spears are cool!

Thanks, Sue and Anne!

Had never heard of “Chekhov’s gun”, but have heard the concept. I believe it was here, as a matter of fact. 🙂

For me, I distilled the post down to this: It’s just hanging there, annoying your reader, who expects it to be relevant.

Never a good idea to annoy my reader; I believe I’ve heard that here at TKZ also.

Thanks again for a great Monday post to chew on the rest of the week.

That’s it in a nutshell, Deb. I think you’d really enjoy Anne’s blog. It’s filled with top-notch advice for writers at all levels.

I tried to sign up on her site, and when I clicked “submit” I got a whole string of computer code, and I’m not sure I’m signed up. Tried to contact her, got the same thing. Maybe you could pass the word along to her. 🙂

I sure will, Deb.

Thanks!

Deb–This is me doing battle with the tech elves again. They only let me leave 3 responses to comments at a time. :-(. I don’t know what’s wrong with MailChimp. I’ve got my webmaster looking into it. As far as you getting weird code if you email me, that’s a whole other problem I’ve never had to deal with before. It seems every scammer/spammer on the planet can use my email address just fine. It may be a matter of clearing you cache, because the bad juju from the MailChimp elves influenced your ability to access gmail. The one thing we can count on with tech is that it goes bad. If you email me at annerallen.allen@gmail.com, I’ll put you on my private–non-MailChimp email list.

I had a problem signing up too. I’m just going to try again later this week in case we blew up your website by visiting around the same time. 😎

Great rundown on applying the Chekhov’s Gun principle, Anne. Very well put. Thanks for visiting us today, and thanks to Sue to driving you over.

“Driving you over…” Haha!

Garry–Yes, I enjoyed the ride in Sue’s limo. Very luxurious. 🙂

Anne has hit the dreaded “too many attempts” error. I emailed our tech guru for a fix. Thank you for your patience!

Sue–Thanks so much for inviting me to the Kill Zone. I’ve been a fan for a long time. You’ve got such knowledgeable readers here! We’ll see if the elves let me post this.

My pleasure, Anne! You have an open invitation here! Thanks for an amazing post!

For me this boils down to a recommendation with context. As Anne notes, Chekhov was a playwright and short story writer who died long ago. Certainly on a short story canvas, his admonition to “Remove everything that has no relevance to the story” is absolutely essential. Otherwise it is unlikely a story could be satisfyingly developed and still fall within the short story boundaries of 1,500-7,500 words. In Hills Like White Elephants, Hemingway showed us how to do it in1,394 words.

When he felt like it, even Chekhov tossed aside his admonition, “If you say in the first chapter that there is a rifle hanging on the wall, in the second or third chapter it absolutely must go off. If it’s not going to be fired, it shouldn’t be hanging there.” He had two loaded guns that were never fired in his famous play “The Cherry Orchard.” Some claim the unfired weapons have relevance as thematically important symbols.

Ernest Hemingway valued inconsequential details and took exception to Chekhov’s bare-bones style saying, “It is also untrue that if a gun hangs on the wall when you open up the story, it must be fired by page fourteen. The chances are, gentlemen, that if it hangs upon the wall, it will not even shoot.”

Other writers maintain too much emphasis on “everything must be there for a purpose” can make a novel too predictable.

I suppose “relevance” is in the eye of the beholder. On the larger canvas of a novel, perhaps we as authors have more elbow room in defining what we mean by the term. In my current WIP the protagonist carries a 38 caliber revolver but he never fires it, though he goes on to kill several antagonists in a variety of unexpected ways. The pistol is a thematically important symbol. That’s my story and I’m sticking to it.

As for not naming a character to keep readers from being disappointed when they assume the character is a very important player, I try to avoid having the tail wag the dog. If the narrative flows better with a name, the character gets a name.

In John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath, starting about page 217 and continuing for a half dozen pages, diner waitress Mae and cook Al , as well as truck driver Big Bill all have names and have some lines to say. They pass into oblivion as the story moves forward. But despite this I believe they have relevance, demonstrating kindness can exist in a grindingly cruel situation.