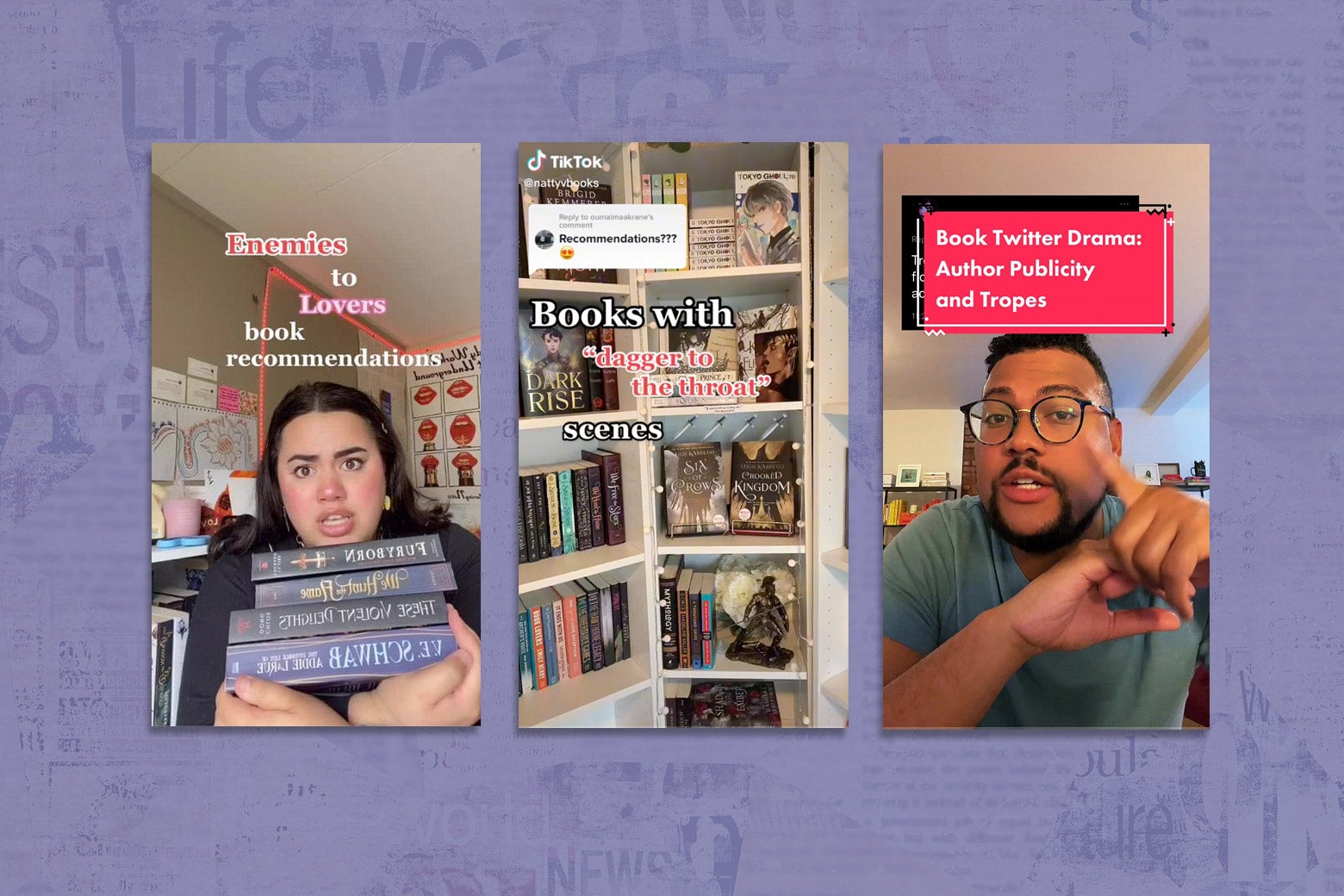

“Everyone always asks, so here you go,” Aaliyah Aroha wrote in the caption of what would go on to become one of her most popular TikTok videos. She appears, lip-syncing to a song from the app-favorite Unofficial Bridgerton Musical and holding a stack of books, as the words “Enemies to Lovers book recommendations” float overhead. The video, posted to her account, @aaliyahreads, which boasts over 216,000 followers, now has 2.5 million views and more than 431,000 likes.

Many book lovers who are in the market for their next read—especially readers who stick to genres like romance and fantasy—turn first to accounts like this. TikTok is teeming with book influencers like Aroha (her last name is a pseudonym), who use their platforms to peddle new releases, make book recommendations, share reviews, and more. But in 2021 and 2022, these content creators found a new way to hack the algorithm—and in turn, the publishing industry. That is, until they began to wonder if they had created a monster.

Among genre readers and editors, depending on whom you ask and their level of involvement with the internet, they’ll register tropes (refer to Merriam-Webster dictionary’s second definition—“a common or overused theme or device”) as the tags used to categorize fan fiction on the site Archive of Our Own (also known as AO3), the backbone of the tremendous fan wiki tvtropes.org, or the internal lingo used in publishing offices to discuss new releases. On TikTok, tropes have become an internet shorthand to help people find their next read. Creators have hacked the phenomenon that is BookTok by using these tropes— “enemies to lovers,” “morally gray main characters,” “fake dating” (the trope where characters must present a facade of affection to the world but end up actually in love—see Simon and Daphne in Bridgerton), “love triangles”—as search engine optimization terms to package their content and convey the “vibe” of a book.

And it works, too. “People want to get straight to the point, so they can read more and read what they know they like,” Aroha said in an email. “It’s a smart way to adjust to the way of society today. I also believe that it’s kept books alive, and people actively wanting to read.”

There’s certainly an audience for it. On TikTok, videos using #EnemiesToLovers as a tag have a total of 4.2 billion views, while #EnemiesToLoversBooks has 78.2 million. Books like It Ends With Us by Colleen Hoover (#FriendsToLovers), The Love Hypothesis by Ali Hazelwood (#FakeDating, #GrumpySunshine), and People We Meet on Vacation by Emily Henry (#FriendsToLovers) became print bestsellers in 2022 after being promoted across the app using these trope tags. There’s almost no avoiding it—trope-ification plays a key part in BookTok’s influence on the publishing industry, especially for the fantasy, YA, and romance genres.

This shorthand categorizes books in a hyper-specific way. On BookTok, romance readers can find a book in which the love interests are forced to share a bed, or fantasy readers can read books with a superpowered main female character (known online as a “magical girl”) or a protagonist who is the “chosen one.” This categorization allows fans to cherry-pick their own adventures or particular happily-ever-afters. It also streamlines the process of picking out books—and creating bestsellers.

“Whatever way you get someone to buy books is a great step for the book industry/community. I also think it helps readers read what they love sooner,” Aroha said.

But some believe that this trend is reductive and rewards authors for simplicity rather than complexity. Hazelwood, the author of the bestselling novel The Love Hypothesis and Love on the Brain, did a controversial interview with Goodreads this past summer that sparked a heated online debate about BookTok’s focus on tropes. Hazelwood, who is open about how she got her start writing fan fiction, explained that Love on the Brain was the first book she had “written from scratch.”

“I kind of didn’t even know where to start, and my agent guided me a lot. She was like, ‘I would love to read an academic rivals-to-lovers story,’ ” Hazelwood told Goodreads, itself a website given to the production of trope-focused lists of genre fiction. “She gave me a bunch of tropes that she wanted me to build the story around, which was really, really helpful because I am very indecisive and had no idea what I was doing.”

This was a bit too much, even for trope-loving fans. People online decried this kind of writing as one of the consequences of TikTok’s trope-ification of literature. The seemingly countless videos describing—or even mislabeling—books using their tropes had, naysayers said, finally come to a head. Tropes, which have typically been seen as clichés that should be avoided in writing, were suddenly present everywhere, according to readers. They thought they were now seeing tropes cited more in marketing copy, author interviews, and newer books like Hazelwood’s.

Readers on TikTok—at least some of them—went from familiarity with tropes to, in 2022, oversaturation. Video creators who addressed this issue said they felt as if newer books were being “built around the tropes.” Readers are now often knowledgeable enough to recognize whether the characters they’re supposed to be invested in were created to fulfill a formula rather than advance a plot.

Josh Lora, who runs the BookTok account @tellthebeees, sees trope-ification as affecting influencers more than authors. Tagging book recommendations by their tropes and genres helps encourage user engagement. “There’s almost a mimetic quality on social media,” Lora, who also uses a pseudonymous last name, explained. “Once you see that something worked for someone else, you start doing it.”

Though many sounded off online about one of the app’s most prevalent trend cycles, it may have already made its mark on the real world. The use of tropes as SEO terms could be playing a part in determining national bestsellers and popular book recommendations on the app.

NPD BookScan, which tracks bestsellers and book sales from major retailers, reported that combined sales numbers for authors featured on BookTok more than doubled in 2021. According to the New York Times, sales for authors featured on BookTok were up another 50 percent by July 2022. Total sales of genre books were up in 2022 as well, whether or not such books were featured on the app. The romance genre saw the most growth among categories of U.S. print books in 2022, while YA fiction kept its momentum after having its best year on record in 2021. Sales of LGBTQ fiction also doubled since the previous year. “Growth has been driven by a variety of authors and series, which were supported by BookTok and word-of-mouth discovery,” NPD books industry analyst Kristen McLean said in a release.

According to Libby McGuire, senior vice president and publisher at the Simon & Schuster imprint Atria, TikTok definitely gets considered in the course of book acquisition. “There are books that we read on submission and think, ‘Oh, we know this reader; we know where to find them on TikTok. We can see that this would appeal to that market,’ ” McGuire said in an interview.

She explained that industry professionals have been using these tropes and terms internally for some time. But now, due to their popularity with the general public, Atria includes these tropes in the book’s metadata so that readers can find something that’s right up their alley. “The consumer has gotten so much more knowledgeable,” McGuire said. “They now categorize the books in the same way that people in the business do.”

At a fundamental level, trope-ification has long been a part of the romance genre. A happy ending, which is the basic element of any romance novel and can be found across the genre’s many subcategories, guarantees romance readers an experience particular to the genre. But no one could have expected that we would one day be able to search for books that have, say, a single knife-to-throat scene.

“There’s this pleasure of the familiarity, which is part of what makes for an intimate, easy type of reading experience,” Catherine Roach said in an interview. Roach is a professor of gender and cultural studies at New College at the University of Alabama, who has also written romance novels under the pen name Catherine LaRoche.

As a fantasy and romance reader myself, I’ve picked up my fair share of BookTok-famous novels to understand what all the discourse was about. There is something thrilling about watching how a book will meet—and sometimes surpass—your expectations, even when you know what tropes it will explore. But that familiarity has its downsides. “If you only ever look for your ‘second chance’ romance tropes, for example, you’re going to miss out on a lot of delightful storytelling that you might have been drawn to or found otherwise,” Roach said. “It can be narrowing and limiting, but it can be efficient.”

Editors and writers planning books around tropes trending on TikTok might have a care in 2023. As Lora pointed out, trends in publishing can be fleeting. Just look at the way Twilight’s success kicked off a subgenre of teen and adult paranormal romance books in the 2000s, while The Hunger Games sparked the dystopian YA boom of the 2010s that bolstered The Maze Runner and Divergent. Eventually, writers and editors of those books saw diminishing returns, proving that producing books based on presumed audience demand has its pitfalls. There may come a time when novels constructed around these particular tropes go out of style once again.