In the mid-’70s, top players in an emerging tournament Scrabble scene persuaded the game’s corporate owner to adopt a universal lexicon for competition. Players manually scraped five standard college dictionaries, recording every unique two- through eight-letter word (plus inflections) that met the game’s rules. When the Official Scrabble Players Dictionary was published, in 1978, players rejoiced. “You can retire the boxing gloves and put up your swords,” the Scrabble Players Newspaper wrote. “You now have an arbiter to settle all arguments.”

In the 44 years since, the OSPD has been revised six times, adding thousands of new words. A seventh edition was released earlier this month. It includes headline-grabbers like COVID, VAX, and DOX (and VAXX and DOXX), and a lowercase variant of JEDI. Also in: GUAC, INSPO, ZOODLE, and SKEEZY. “You’ve got some fun new words,” said Peter Sokolowski, editor at large of Merriam-Webster Inc., which has published the OSPD since its inception.

Hidden by the buzz over the latest lingo, though, is an underlying truth about chronicling our ever-evolving language: The American dictionary business is slowly dying. Of the publishers of the OSPD’s five original source books, Merriam-Webster is the last with a staff of full-time lexicographers producing regular, robust updates, all of it now online. The others are either defunct or ghost works updated rarely and modestly by freelance lexicographers, and have either no web presence or a stagnant one; a recent print edition of one of them boasted “dozens” of new words and senses, which is not a lot of new words and senses. (Merriam does issue new printings of Merriam-Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary, the primary Scrabble sourcebook and the basis for its free online dictionary, with some of its new words, but the last full overhaul in print was an 11th edition, published in 2003.)

“The decline of the dictionary in the U.S., the lack of competition, means less of everything,” Michael Adams, an English professor at Indiana University who studies lexicography, told me. “When dictionary programs try to include more words and respond to the needs of niche markets, we all benefit. But when there’s no competition, no one needs to think about serving the Scrabble community or any other community.”

Chronicling the evolution of American English is undeniably culturally significant—the words we use are who we are—but the nitty-gritty of word histories, etymologies, and pronunciations might seem academic or esoteric. After all, Google fulfills almost any quotidian lookup need. But the words in Google’s dictionary are licensed from Oxford Languages, publisher of the Oxford English Dictionary. That’s a British source, which matters in terms of focus. In the United States, the only active dictionary-maker besides Merriam is Dictionary.com, which was founded in 1995 and bought in 2018 by the mortgage loan provider now known as Rocket Companies Inc. Merriam, which dates to Noah Webster’s first dictionary in 1806, has been owned since 1996 by privately held Encyclopædia Brittanica Inc. Both dictionaries were acquired because of a rich guy’s quirky personal interest. Their business futures are anything but guaranteed.

“What’s interesting for [American] dictionaries is that it was such a competitive marketplace, and now it’s nothing,” said Lynne Murphy, a linguistics professor at the University of Sussex in Brighton, England, and author of The Prodigal Tongue: The Love-Hate Relationship Between American and British English. Unlike French, which is monitored by a highfalutin council, American English has, for better or worse, never had official governmental backing, Murphy said, “and therefore no institutional support except for the marketplace.”

Competitive Scrabble is one domino in the industry’s downturn. The seven editions of the OSPD were, in aggregate, constructed from more than two dozen different editions, printings, or online updates of nine dictionaries from six publishers. Tournament players—and, in the 1990s, a reclusive list-maker named Joe Leonard—compiled lists of candidate words from the source dictionaries. Merriam editors then curated the list and wrote the book’s entries, with a part of speech, inflections, and a short definition.

The new words in the latest OSPD update come only from Merriam, and were culled from more than 4,300 words added online from 2018 through 2021. Why the solo effort? Partly because there are no standard North American dictionaries left untapped. The last time Scrabble players poached words from outside sources was 2014, when they combed the Oxford American College Dictionary (last published in 2007) and the Canadian Oxford Dictionary (2005), which supplied some cool newies like QAJAQ.

The shortage of other dictionaries isn’t a problem for Merriam-Webster. It publishes the OSPD under an agreement with Hasbro Inc., which owns Scrabble in North America. A few hundred new words every five years or so is plenty to justify a new edition of a book aimed at living-room players who want the latest in language—SPORK, BAE, ZONKEY, and HYGGE adorn the seventh edition’s redesigned cover. Including non-Merriam dictionaries has been a cause driven by competitive Scrabble players like me. More new words means more opportunities to score more points—and fewer dictionaries means fewer new words and fewer scoring opportunities.

By that standard, the OSPD7 is a modest update. Of the 489 total additions—a list is circulating like samizdat in the competitive Scrabble community—more than half are inflections of new words or new inflections of existing words. VERB, ADULT, and PANTS are now verbs. So is AT, as in “don’t at me.” INKING is pluralizable. But there are no new two-letter words, and no huge game-changers, like when QI and ZA rocked Scrabble in 2006, or even when OK landed amid debate in 2016.

Still, players are psyched. Jeffrey Pogue, 18, of Westport, Connecticut, a former North American youth Scrabble champion, discovered that Merriam had updated its Scrabble Word Finder website before releasing the physical book. Pogue figured out a way to extract the words, compared them against a previous digital version of the OSPD, and compiled lists of new three- and four-letter words and new words containing J, Q, X, or Z. “I love seeing new words, just because they are shiny and new and feel like new toys to play with,” he said.

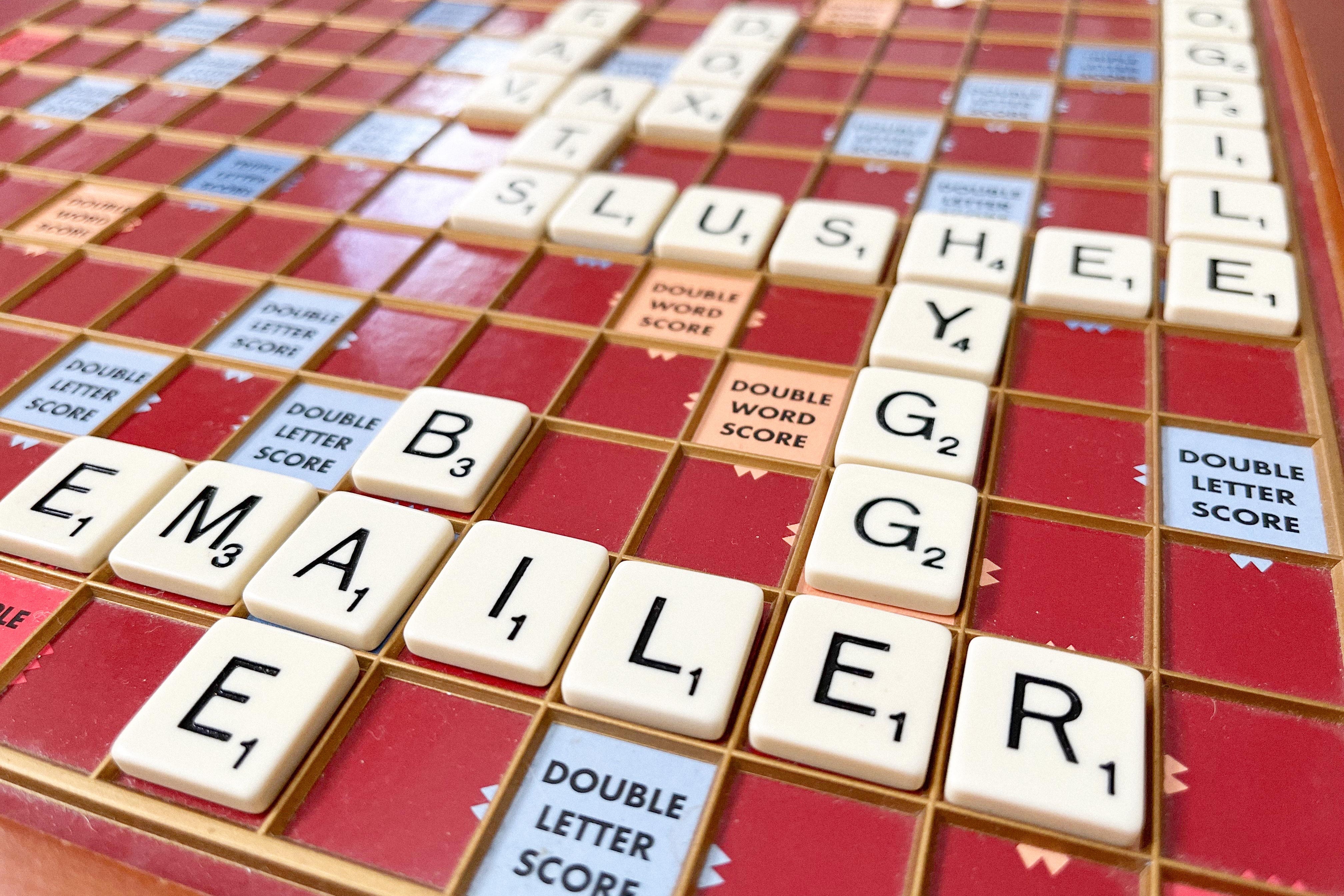

Debutantes FAV, FOLX, QUESO, YAJE, and ZUKE will add short scoring opportunities with high-scoring or clunky letters. AMIRITE (anagram: AIRTIME) and EMAILER will be high-probability bingos. ATS and ARO will open new ways to “hook” two-letter words. And if the chance ever arises, I’ll lay down SHOUTOUT (anagram: OUTSHOUT), EGGCORN, NUTBALL, FAUXHAWK, or SLUSHEE (anagram: HUELESS) with glee. “It’s nice to see pieces of my own vernacular start to be usable in Scrabble,” said another young player, 17-year-old Emmett Brosowsky of Washington, D.C. (whom, full disclosure, I’ve coached for several years). “It’s almost a form of representation.”

The lexicon governing play at most clubs and tournaments in North America differs from the corporate-owned OSPD. The competitive list is managed by NASPA Games, an independent nonprofit formerly known as the North American Scrabble Players Association. It includes all of the OSPD plus much more: tens of thousands of nine- to 15-letter words; dialectical spellings like SEZ, WUZ, YER, KINDA, SORTA, and OUTTA; trademarks like KLEENEX and VASELINE; and some offensive words excised by Hasbro and Merriam in the 1990s. (NASPA removed slurs, but not garden-variety profanity, from its list in 2020.) The OSPD contains more than 100,000 words; NASPA’s list totals around 190,000.

When the latest update takes effect in clubs and tournaments, probably by next summer, the lexicons will diverge even more. NASPA’s chief executive, John Chew, told me that the organization might include words entered by Merriam after the deadline for the print OSPD, including PWN, LARP, YEET, and JANKY. It also might retain around 100 words Merriam deleted from the new OSPD, some of which have offensive meanings in addition to inoffensive ones, or might just be seen as inappropriate. One example: SEG, which was defined in the sixth edition of the OSPD as “one who advocates racial segregation.”

But there are scads more new words as-yet undefined by Merriam’s small editorial staff. (So many words, so little time.) A few years ago, I embedded at Merriam as a lexicographer-in-training and drafted or identified more than 100 potential entries. A dozen of them have made the dictionary, including new OSPD additions DOGPILE and HEADBUTT (anagram: BUTTHEAD). But two potential Scrabble cluster bombs—the nonbinary pronouns ZE and XE—have not. Scrabble isn’t just missing out on extra neologisms, though. The decline of American dictionaries also means fewer vanilla additions, like derivations and inflections, which would bolster the game’s list even more.

So what are Scrabble’s options for lexical growth? Chew said he has considered trawling specialty dictionaries, like law or medicine, and reexamining the American Heritage Dictionary, an unabridged book in all but name that was used for the first OSPD. Dictionary.com has verticals on slang and gender and sexuality that could offer lots of trendy and important words. Or NASPA could judiciously tap crowdsourced word sites or do its own lexicography. Chew, who is the chief editor of a planned dictionary of Canadian English, during a previous update instructed members of NASPA’s dictionary committee how to collect “citations” for words from published sources to justify inclusion on the Scrabble list.

It’s a balancing act. For most North American tournament players, a few hundred new words every few years is manageable; thousands, especially without the imprimatur of professional dictionaries, might cause a revolt. Others want lots more words, and don’t particularly care where they come from or the state of American lexicography. In recent years, dozens of North American players, including some top experts, have migrated to tournaments governed by a British-based source, Collins Scrabble Words, that consists of a whopping 280,000 words. Switching to that list has been a political nonstarter for NASPA.

I fall somewhere in between. I’m unwilling to devote the time required to study the sprawling international lexicon but also concerned that the reduction in established North American word outlets could stagnate the domestic game. Because new and diverse sources not only ensure that Scrabble reflects the latest in language; they keep a board game approaching its 85th birthday strategically dynamic, too.