Editor’s note: To celebrate the “Season of the Witch,” as it were, in October we will be featuring our Classics of Pagan Cinema series on Sundays. This week, we have the fabulous Meg Elison writing on Terence Fisher’s The Devil Rides Out, arguing that perhaps it should not be included in our Pagan Cinema canon.

Friends, your humble correspondent tries to do her best for you, every time. When I chose to write about The Devil Rides Out, Terence Fisher’s 1968 British horror production, I thought the best thing to do would be to read the 1934 novel by Dennis Wheatley first. I did the same thing with “The Eye of the Devil,” because I wish to amuse you in a way that is both thorough and well-informed.

Wheatley’s novel made me regret my work ethic and want to give up.

Novels from the 1930s often contain uncomfortable artifacts of their time, and this one is no exception. A duke finds that his nephew is involved in the occult and resolves to save him from it. How is this occultism described by the book, you may ask? Why, with the fearsome figures of Black men, and religious practices of Afro-Caribbean syncretism. I was quickly satisfied in my desire to read this book when each and every person of color was evaluated for their physiognomy to determine their origin and relative docility (the phase: “My god, a Malagasy!” is offered more than once) and yet I read on.

The work of prose does not improve.

Undaunted, I made my way to a poor-quality stream of the film, heartened to at least be privy to a performance by Christopher Lee, giant of Star Wars and Lord of the Rings fame, as well as a multiple entrant into the canon of Pagan cinema classics (stay tuned for The Wicker Man, gentlefolk). Squared up against Mocata (Bond villain Charles Gray) and on the subject of baneful magic, I thought I was in for a treat.

A still from “The Devil Rides Out” featuring a goat’s head sigil (1968) [Film-Grab]

My spirits fell once more during the opening credits, which used the familiar symbol of a goat’s head in the inverted pentagram to let the audience know that dangerous magicks were afoot, but this was not the cause. Among the many sigils displayed over the credits, one caught my eye. It was an inscribed illustration of two hands giving the blessing of the Kohanim, the Jewish priestly class later Vulcanized as the “live long and prosper” salute by Leonard Nimoy’s Spock in Star Trek. A great deal of ink has been spilled over the cultural appropriation of Jewish mysticism by Witches and Pagans, but I think the confusion arises largely from undifferentiated collections of spooky shit like this: schlock horror, cut-and-paste grimoires, and the like.

My standards thus set low, I let the film roll on.

Imagine, if you will, that you’re throwing a party for your coven. Everybody is dressed up and the table is set. There’s music playing and tonight is an auspicious night. You’ve made preparations, cleaned out the ritual room, and bought supplies.

Then your stuffy rich uncle pulls up and knocks you out, kidnapping you from your own home and place of practice. He hypnotizes you into wearing a large crucifix and tries to keep you locked up at his house until the moon or the sabbat has passed.

That’s what happens to Simon Aron (Patrick Mower), who isn’t the protagonist of this film – he’s just a person who things happen to. No, the protagonist is the uncle, the Duc de Richleau (lamentably, Lee) who sees that his fully adult nephew needs to be saved from himself.

The dangers of the occult become clear when an invocation is spoken and a Black man appears. I’m not kidding. It’s literally just a Black guy standing there, no weapons or obvious supernatural powers, who makes no moves and does nothing, while Richleau screams that no one should look him in the eye. The acts of magic move on from there: a white goat is sacrificed and a human sacrifice is promised thereafter. The film makes it clear that only young white women are acceptable sacrifices.

The place is crawling with young white women, thank the gods. Our heroes truck it out to Salisbury to save white girls like Tanith (Niké Arrighi) from the danger that threatens them there. The danger, shown plainly in dead boring cinematography, starts with old men in Klan-looking robes reenacting an episcopal service – but evil, somehow – followed by drumming and orgiastic dancing.

This would be enough to infer that the behaviors feared as “satanic” by the protagonist are those one might associate with pre-colonial religions, but just in case the viewer is not clear, a Black actor wrestles with a white woman (though they are both adherents of the same sect and present for the same ritual), seeming to force her to drink blood from a goblet.

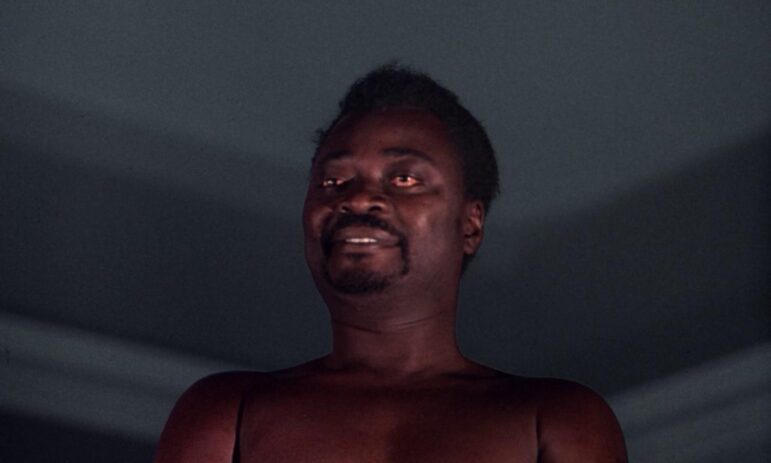

Yemi Ajibade, whose performance in “The Devil Rides Out” (1968) was uncredited. [Film-Grab]

The Black actor is uncredited in the film, but a little digging on British-African performers turns up some interesting information. The actor is a man named Yemi Ajibade, born a prince of the house of Ọ̀ràngún in Nigeria. Ajibade enjoyed a long career, acting on both stage and screen from the 1960s until just a few years before his death in 2013. He was also a playwright, creating new works for British stages, some of them touring nationally. That the film does not bother to credit this man seems the ultimate expression of how silly this whole business is. This film is nasty, small, boring, mean-spirited, and racist.

Most of the plot revolves around acts of magical warfare flying back and forth between Lee and Gray, played out in the possession and torture of the women in the film. The duke’s niece Marie (Sarah Lawson) and her daughter Peggy (Rosalyn Landor) are the notable foci of this demonic work, but they have no individuating features other than wide eyes and receptive bodies. They are fought over by the good and evil men in the tale, laid on altars like food on the table, tossed around hysterical for the good of the spectacle. Not one of them wants something of her own.

Richleau, looking like a mirror universe Lord Summerisle with his bad goatee, is an unlikely hero. He’s rash and emotional, making poor decisions and pulling his tools only from the toolbox of his enemy. When the left hand path threatens his family, he makes a brief show of invoking his own god. He uses a crucifix, and when he inscribes a magic circle on the floor, it is one that contains some of the names for both his god and his god’s son. However, Richleau does not offer Christian prayer in defense. He does not call upon the vicar to exorcise or quell a demon that he literally believes can kill everyone else in the house. He swears up down and side to side that he should not use the magic he knows unless the circumstances are absolutely dire.

And when circumstance comes, what is that magic? It’s a stripped down version of the lesser banishing ritual of the pentagram. Is there a sad trombonist in the house?

A still from “The Devil Rides Out” (1968) [Film-Grab]

This milquetoast mysticism pulls off a dubious ex machina in the final act. The dark ritual of sacrifice is ended, leaving the white girls intact. The bad guy is dead because Richleau’s spell reversal is so algebraically balanced that Mocata doesn’t even leave an indecorous corpse behind. The nephew, who was formerly a member of a coven, has seen the error of his ways. The temple erected for this unholy rite has burned away, leaving an unblemished (and ghastly ugly) Christian chapel in its place. Time itself has reversed, so that none of the events of the film ever happened. (Yes, really.) Does this time warp affect the rest of the world? Was it the result of the weak ceremonials Richleau pulled off? The answer is singularly unsatisfying.

Finally, Richleau says that they must thank their god for this victory, and everyone agrees. I don’t know about anyone else, but I never saw that guy lift a finger. Nobody called Jesus, and Jesus certainly never came.

“The Devil Rides Out” is a limp fistful of failure in the canon of Pagan cinema classics. As much fun as it sounds to watch Christopher Lee do the lesser banishing ritual, there’s no glee in it.

This film is like a glass case at the British Museum: a racist display of stolen mysteries that should just be put back where they were found.

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.