It’s hard to talk about meat, dairy or egg farming without talking about poop.

Manure plays a big role on American factory farms, and if not properly managed it can quickly turn into a big problem. Each year in the US livestock animals produce between 1.27 and 1.37bn tons of waste – or somewhere between three and 20 times more manure than people produce in the US.

That’s partly why devices that take manure and turn it into an energy source are catching on – as a way to manage waste and reduce methane emissions on farms. All that waste has to go somewhere, and many of the existing options aren’t great for us or for the environment. Manure from animal agriculture is a primary source of nitrogen and phosphorus pollution in US waterways, making water undrinkable and causing algae blooms that kill wildlife. Manure is also a significant source of greenhouse gas emissions on livestock farms – and much of its impact depends, specifically, on how it’s managed and stored. Twelve per cent of all greenhouse gas emissions from the US agricultural sector come from what the EPA calls “manure management”.

So why not turn all that pollution into something that can power vehicles and other farming equipment – or into something that can be sold and used off-farm? This is the supposed promise of anaerobic digestion. In the past five years, there has been a surge of partnerships between animal farms and natural gas companies promoting the use of anaerobic digesters, which turn manure into a form of energy called biogas. The EPA has identified more than 8,000 dairy and hog operations as prime candidates for future on-farm digesters. Amid talks at Cop26, the Biden administration pointed to an expanding biogas industry as crucial to its methane emissions action plan. Smithfield, Perdue and Chevron all announced digester partnerships in the last two years.

The waste-derived biogas industry appears to be booming; globally, the industry is predicted to reach $126.2bn by the year 2030, more than doubling over the next decade.

But digesters come with their own set of problems. Some critics worry that the rise in this technology will only make it harder to curb the carbon footprint of animal farming and transition to greener energy sources – two things we must do in order to slow the effects of the climate crisis.

Tyler Lobdell, an attorney with Food and Water Watch, says his group is particularly concerned that the rise in digesters only serves to further entrench both natural gas and factory farm production – two industries that are already notoriously difficult to regulate. “We’re marrying these two industries in such a way that it will become very difficult to advocate for change,” he says.

Depending on how they’re used, anaerobic digesters may also not be as effective at curbing air and water pollution as they are on paper. “We already don’t enforce regulations on the books for air and water in CAFOs,” says David Cwiertny, a professor of engineering and environmental policy at the University of Iowa, referring to concentrated animal feeding operations. “I’m hard pressed to believe we’ll do it for digesters.”

If properly managed, digesters could help polluting CAFOs get their manure under control. And good manure management – that is, following the best practices for collecting, storing and applying manure as a fertilizer – is critical for curbing pollution. But every type of animal farming operation is different, and brings different logistical hurdles for digesters. Plus, getting good at producing natural gas also means farms are now tasked with finding something to do with it.

How it works

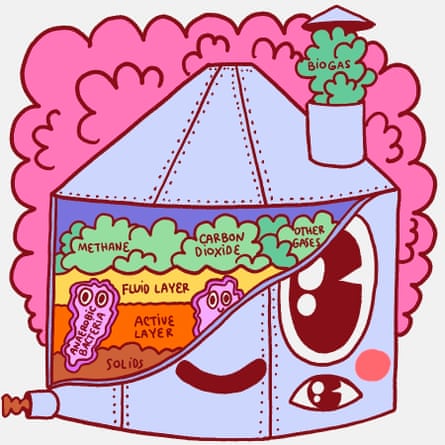

Anaerobic digesters use bacteria to break down organic matter in an oxygen-free environment, like a sealed reactor or lagoon. Gases such as carbon dioxide, water vapor and methane are then separated from the liquid and solid digested waste, and the system can then process the biomethane so it can be used as natural gas.

That natural gas can be used as an on-farm power source or sold to a gas treatment system or local utility. What’s left over – the solid and liquid digested waste – is then stored until it can be applied to cropland, or sold to other farms or garden stores as livestock bedding or potting mix.

This storage solution could help on industrial pig farms, where manure is typically stored in pits or “lagoons”. Lagoons especially can become ticking ecological timebombs when a storm comes through. Heavy rainfall can lead to manure overflowing into nearby lakes and even well water. “Sometimes things happen where these pits fill up faster than what they expect,” says Chris Jones, a research engineer at the University of Iowa who studies water pollution.

Normally, when preparing for a storm, CAFO operators have to get the manure out right away to avoid overflow. But when used properly, digesters are a sturdier solution that keeps the manure away from the rain, which can help curb runoff and overflow, as well as odor pollution. It can also reduce methane emissions in an industry that sorely needs it. Methane emissions from hog manure storage are higher than in any other livestock operation, except for dairy cattle.

Why it might be less effective than it looks

Critics warn that manure digesters shouldn’t be used to justify the expansion of factory farming, which is already a huge contributor of greenhouse gas emissions globally, as well as local air and water pollution.

In Nebraska, one hog farming operation installed digesters after expressing concerns about how their expansion to 8,000 hogs would affect the surrounding community. And in California, public investment in digesters has gone overwhelmingly to larger operations, which incentivizes further consolidation in the industry in pursuit of profits from selling natural gas.

But digesters can’t help reduce methane emissions everywhere on a farm – and that’s especially a problem on dairy farms.

Cattle are the highest methane-emitting livestock animal because of the way cows digest food. Unlike most other farmed animals, most of cattle’s methane emissions come from belches, not manure. And those methane emissions, known as enteric methane emissions, are responsible for a large chunk of overall greenhouse gas emissions from the food sector in the US – 25% by EPA figures. But digesters do nothing to address enteric methane.

Research also suggests that dairy farms can reduce their methane emissions by using solid manure storage. However, virtually all the digester projects in California that launched in the last year rely on covered lagoon systems, not solid storage.

Is this renewable energy, or greenwashing?

Anaerobic digesters may be able to extract energy from manure, but critics like the Food and Water Watch say that isn’t worth the risks associated with producing natural gas on farms. Transporting biomethane (as well as selling the manure that’s left over from the process) is expensive and complicated for livestock farmers, and while rare, accidents can happen. Digesters that aren’t carefully maintained can also leak, explode or break down, requiring professional divers to carry out risky repairs. Last July, a diver hired by an Iowa farmer drowned in the manure tank trying to fix a cable.

Ultimately, the biggest concern about the rise of these technologies is that they’ll be used to distract from the country’s need to move away from energy sources like natural gas.

“This allows [farms] to talk about their existing natural gas infrastructure as though it’s changing and becoming sustainable,” says Food and Water Watch’s Lobdell, “when in reality, there’s really no difference.

“If we reach a point where municipalities and states are dependent on factory farms to source their energy […] the argument [becomes] ‘well, you’re not going to have electricity tomorrow if we close down a factory farm.’”