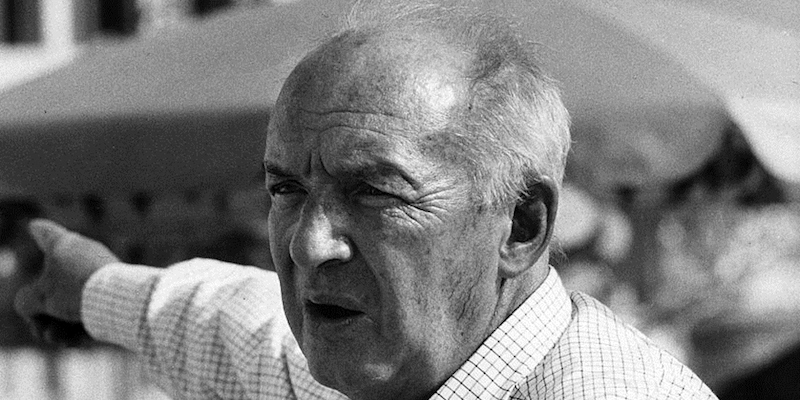

Why Nabokov’s poem about Superman’s sex life was rejected by The New Yorker.

Before Pale Fire, or Pnin, or Lolita, Vladimir Nabokov was just like some of us: sending poems to the New Yorker. Nabokov—already famous in Europe for his Russian-language works—was suddenly plunged back into obscurity when he relocated to America, and attempted many projects in different genres hoping to recapture career success. One such project, as brought to our attention by the Times Literary Supplement: “The Man of To-morrow’s Lament,” a rhyming poem in the voice of Superman, which explores the idea that Superman is too strong to successfully sleep with his girlfriend.

The poem, long believed to be lost to time until earlier this year when Russian scholar Andrei Babikov unearthed it in Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library’s archives, was written at the suggestion of Nabokov’s friend Edmund Wilson after Nabokov mentioned he had been reading Superman comics at night to his son. But “The Man of To-morrow’s Lament” is clearly not a poem for children: it devotes all of its 46 lines to detailing the ways in which getting horny would wreak havoc on Superman’s life and the world at large. For instance, this is what would happen on Superman and Lois’s wedding night:

I’m young and bursting with prodigious sap,

and I’m in love like any healthy chap –

and I must throttle my dynamic heart

for marriage would be murder on my part,

an earthquake, wrecking on the night of nights

a woman’s life, some palmtrees, all the lights,

the big hotel, a smaller one next door

and half a dozen army trucks – or more.

Superman goes on to hypothesize that even if his “blast of love” didn’t manage to kill Lois with its power, she would go on to have a terrifying supersized child: “What monstrous babe, knocking the surgeon down / would waddle out into the awestruck town?” For these reasons, Superman is depressed, feeling “no thrill in chasing thugs and thieves,” and “when [Lois] sighs—somewhere in Central Park/where my immense bronze statue looms—“Oh, Clark . . . / Isn’t he wonderful!?!”, I stare ahead / and long to be a normal guy instead.” Sad!

This poem is evidently not for everyone. Nevertheless, Nabokov eagerly sent the poem to the New Yorker, who had previously published his poems “The Refrigerator Awakes” and “A Literary Dinner” and had requested more of Nabokov’s work. It was rejected by Charles Pearce, New Yorker poetry editor at the time, pretty even-handedly: Pearce mentioned that the hotel section was a bit risqué, and said, “Most of us appear to feel that many of our readers wouldn’t quite get it.”

Interestingly, Pearce’s rejection might not have been as sex-oriented as he told Nabokov, considering Nabokov went on to perform the poem at religious women’s colleges to delighted audiences (!). As Andrei Babikov points out in the Times Literary Supplement, this poem made light of Superman’s might in a time where Superman had just become a symbol of wholesome American military power. And, images in the poem (the “dark-blue forelock on my narrow brow”) visually linked Superman to Hitler (albeit subtly)—indicating a critical perspective on American nationalism, which the New Yorker would be loath to publish at the time. You never know what will get you rejected.

The full poem—as well as Nabokov and Pearce’s exchange of letters—can be read here, courtesy of Andrei Babikov, The Wylie Agency, and the Times Literary Supplement.