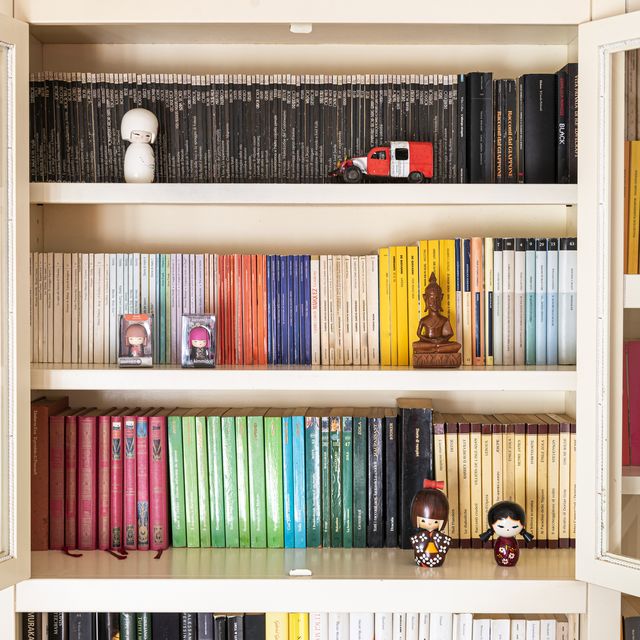

On a Zoom call last month, in the middle of answering my question about his new HBO show Lovecraft Country, Courtney B. Vance interrupted himself. “I love your bookshelves,” he said. “Can you come over and do mine?” A few months earlier, Hollywood actor Darren Criss did the same after noticing the shelves standing behind me.

Moving back to my childhood bedroom for the pandemic has had an unexpected perk: A built-in Zoom background. My designated space for video calls is right in front of a row of red novels that transitions into yellows and finishes at blues, a small portion of my shelves’ floor-to-ceiling color spectrum. Once the pride of my childhood, my rainbow-organized bookshelves shelves have now become the perfect ice-breaker—and, inevitably, argument-starter.

For all of the people who have complimented my shelves, the same amount have also questioned my sanity. One colleague scowled upon seeing my Zoom backdrop, saying she discounts bookstores and people who arrange their books by color. A potential romantic prospect was convinced I must not be reading the books on my shelf.

"I admit that when I see books color-coded, I rush to judgment," says O's books editor Leigh Haber. "It's like people who buy fake books for decor or whose decorators purchase books on the basis of how they'll look on coffee tables. Books aren't decor!"

I’m far from the only reader to receive this kind of feedback: The debate about whether or not color-coding bookshelves is vain or genius is an argument that has raged among book lovers for years.

Back in July, author and journalist Jen Ashley Wright was the latest to find herself in a major Twitter showdown after sharing a photo of herself standing on a ladder next to her custom-built, floor-to-ceiling bookshelves. “I feel like coordinating books by color is one of those things you either love or are wrong about,” Wright wrote in the caption.

Wright tells OprahMag.com she previously organized her substantial library by authors’ last names. But when she and her husband moved to a converted church, they decided to install show-stopper shelves to complement the stained glass windows of their new living room. “It’s a place that’s filled with color. I wanted to bring that to this huge, blank wall. The way to do that was to coordinate by shade,” Wright says.

Almost immediately after posting, the Twitter mass descended on Wright, bristling at her taking joy in what was, to them, the wrong way to organize books. “This makes me unreasonably mad,” one commenter wrote. Another said, “Only someone who doesn't read books would do this.” Some snarkily cited the difficulty of tracking down a book: “That's great if you care more about how your books look than ever being able to find one.”

But Wright says the system actually works better for her on a functional level. “I’m more likely to remember what a book looked like than to remember who wrote the book,” she says. “I cannot for the life of me remember who wrote My Friend Anna, but I know it was pink.”

Our own books editor Haber adds that while she's anti-color coding, her own book system could probably use some better organizing. "My opinion should probably be taken with a grain of salt—there is no room in my house except the bathroom that doesn't have piles of books stacked in random spots, in no particular order. That's my feng shui."

Ultimately, over 1,000 people responded with their opinions—because, as Wright correctly identified with her tweet, this is a topic people have opinions on. The incident was so acrimonious that it several articles, like a story from LitHub posing the age-old question in its headline: “Why do people on the internet care so much about how other people organize their books?”

Color-coded bookshelves have existed for years, especially at bookstores. A 2006 essay in Design Observer was one of the first articles to seriously weigh the merits of a rainbow shelf in one’s home. “The more you look, the more you see an enthusiasm for color-coding in every corner of our culture,” Rob Giampietro wrote, predicting the trend with eerie accuracy.

Thanks to a convergence of Pinterest, the rise of DIY culture, and the appeal of Bookstagram, color-coded bookshelves have since transitioned from novelty to a common trend in people’s homes. Before they became a fixture of her Instagram feed, bookstagrammer Nnenna Odeluga remembers encountering color-coded shelves running above the checkout line at New York’s famed Strand Bookstore. Today, her vibrant shelves greet guests in the entryway of her New York apartment. “It had been a plain white wall. Now, it makes a statement,” Odeluga says.

More recently, we likely have Clea Shearer and Joanna Teplin, the mavens behind the massively popular organization company The Home Edit, to thank for the design trend's popularity. The Home Edit is known for sorting everything, from bookshelves to pantries to LaCroix stockpiles, into color-coordinated (and supremely Instagrammable) compartments. “Everything we do is supposed to have an aesthetically pleasing quality. But everything we do functions,” Teplin tells OprahMag.com. “The rainbow is a practical organizing system.”

Founded in 2015, the Nashville-based company boasts nearly 2 million Instagram followers, and fans include celebrities like Gwyneth Paltrow, Khloe Kardashian, and Reese Witherspoon; in fact, it was Witherspoon's production company that created the Home Edit’s brand-new Netflix Show, Get Organized with The Home Edit.

Throughout the Netflix series, Shearer and Teplin conduct their interviews in front of a color-coded bookshelf similar to my own, the ultimate symbol of their ROYGBIV-governed philosophy. “At first I just started loving [color-coded shelves] because they look beautiful. But there really is a system to this. Books are easy to find and easy to put away,” Shearer says.

Teplin and Shearer especially encourage color-coding bookshelves for children, who can easily slide books to where they belong. “I love that their parents think that their kids understand the dewey decimal system, or the alphabet. Do you want the kid to help clean up or not?” Teplin jokes.

As the blowback to Wright’s tweet demonstrates, however, not everyone shares the Home Edit’s mindset, particularly when it comes to books. To color-coding skeptics, the arrangement signals priorities that are antithetical to books themselves. That’s the thing about books: They’re not just objects—they’re markers of aspiration. Of selfhood, even.

“We use books as intellectual markers of accomplishment. Of how smart we are, or how cultured we are. We’ve read the right things. They become emblems of ego,” private librarian Christy Shannon Smirl, owner of Foxtail Books, says.

With this mindset, a bookshelf becomes a trophy collection as well as a declaration of values. The self, manifested in rows of rectangles. “Bookshelves are a picture of our identity. Our past. Of places we’ve traveled, things we read in college, things we want to read,” Smirl says. “In a room of books, you can give evidence of the many different parts of someone’s life. There’s no other object in the home we can do that with.”

This might explain why people are so judgmental about color-coded bookshelves. If shelves are reflections of the self, then to see another person’s book collection is also to evaluate and judge their book collection—and judge them. “There's a reason that when we are in someone's house, we're curious about what's on the shelves—because we're wondering who they are,” Smirl says.

What, then, does a color-coded bookshelf signal about a person to inspire such blowback? Perhaps that they are not serious about books. “It’s a gatekeeping attitude,” book designer Lauren Ipsum says. “It’s the same as snobbery around ebooks and audiobooks.”

Wright also attributes the vitriol to internalized misogyny, either outright or unconscious, since many of the organizers of rainbow-coded shelves appear to be women. “There’s a certain anger towards young women being interested in things that are aesthetically pleasing, fun, and whimsical, and things that have been taken as a serious man’s domain,” Wright says.

“If the goal is to make them take me seriously, I suppose I can arrange all of my books alphabetically, and I can wear a tweed suit with my glasses, instead of contact lenses. But then they’ll just say I’m a bitter shrew,” she adds.

Given the symbolism of a book as an object for many bookworms, to acknowledge the existence—let alone the importance—of its cover, as Wright did, has always been somewhat taboo. Rainbow bookshelves defy that cardinal, if unspoken, rule of book-buying. Not only do these bookshelves acknowledge books’ aesthetics, they celebrate them.

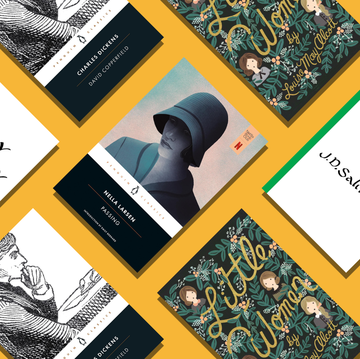

But to a certain degree, isn’t the point to judge a book by its cover? Publishers pour money into book marketing for that very reason. “When it comes to my work, I do book design under the approach that you should be able to judge a book by its cover. I want someone to get an idea of what’s inside, based on the cover,” Ipsum says.

Walk into a bookstore, and each book sends a message to consumers—and then, once purchased, sends a message to the people browsing your shelves. Ipsum says that books’ colors are chosen deliberately, through color psychology, down to the side of the book. “We spend time on the spines. This is a thing we think about, and is very intentional,” Ipsum says.

By disrupting the Dewey Decimal or the alphabetical system, the rainbow bookshelf may inspire other conversations and connections to spring up between books. Two books with red spines, for example, may be classified as different genres, but could have a mood in common.

Unless you turn bookshelves so the pages are facing outward (another controversial organizing tactic), the books’ spines will exist on the bookshelf, and will serve a purpose. Ultimately, when organizing a personal library, the only question that should matter is: What purpose should the book serve for you, and the system you’ve devised?

Libraries and bookstores don’t organize their collections by color, because they need the system that works the best for the most number of people. However, their own methods vary, location by location. "Bookstores, libraries, public libraries, and academic libraries all have different organizational systems. Often people think it’s just one type of system, and it’s not,” librarian Kerry Leek says.

To the same degree, everyone has a different method for their own system for their personal system. “Books are to be findable for you,” Leek says. “You need to be able to find the book. For some people, it’s a stack of books next to their bedside.” For others, it’s alphabetical by author, or arranged by subject, or by title.

Certainly, not everyone remembers books by their color scheme. But some people, especially those well acquainted with their collection do—I know, because I’m one of them. During her decade working as a librarian, Leek has often encountered patrons like me, more likely to remember the appearance than the title. “People will say, ‘I don't remember the title. I don’t remember the author. But I remember the color is blue,” Leek says.

Ultimately, bookshelves are inherently personal, both in their contents, and in how those contents are arranged. Though in her time as a personal librarian Smirl has dismantled rainbow shelves more than she’s put them together, she maintains that books are meant to be played with.

“They’re easy design objects to play around with in your house. They are lightweight. You can change things up quickly,” Smirl says.

My diehard commitment to color-coded bookshelves remains one of my most controversial opinions, right up there with ketchup being disgusting. (Have you actually tasted the red goop?) Or airports, in the “before times,” actually being pretty wonderful to hang out in for hours. (They are!) But just like those opinions, my shelves aren't going anywhere, no matter what Twitter says.

Go ahead, judge me. I’ll be busy reading.

For more stories like this, sign up for our newsletter.