Venice Architecture Biennale: How Will We Live Together with Peter Mörtenböck + Helge Mooshammer

Part two of our Design and the City episode covering the long-awaited 17th Venice Architecture Biennale featuring the Austrian Pavilion curators, Peter Mörtenböck + Helge Mooshammer on platform urbanism and what that means for the future of our cities.

The postponed 17th Venice Architecture Biennale asked its 112 participants to consider the question, “How will we live together?”. A question originally posed in 2019 by curator and architect, Hashim Sarkis far before our collective 2020 experience. Sarkis originally asked participants “to imagine spaces in which we can generously live together” Answers from 46 countries materialized into the exhibition of 2021. After a year spent living apart, the theme is both hauntingly fitting and reifies our disconnection.

Listen to part two of our special episodes on the 17th Venice Architecture Biennale on Design and the City now:

It has signalled something, a community eager to reconnect and a deeper understanding of just how interwoven we are with our spaces spanning the full spectrum of human existence. The exhibition explores that spectrum across five scales: Among Diverse Beings, As New Households, As Emerging Communities, Across Borders, and, As One Planet.

Austrian Pavilion: We Like Platform Austria

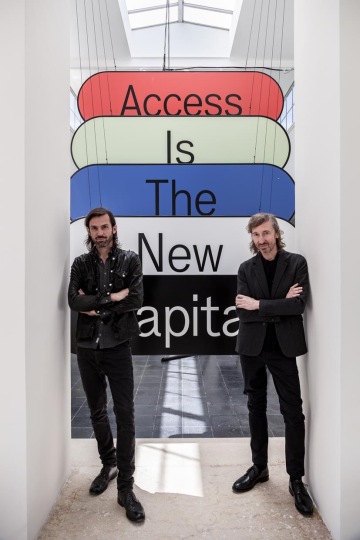

This year’s Austrian Pavilion entitled, We Like Platform Austria, addresses a fundamental yet overlooked impact digital technology platforms have on contemporary architecture and urban development. Curators, Peter Mörtenböck and Helge Mooshammer, turn the pavilion into a platform in itself to challenge the global monopoly exercised by platform enterprises, and the imagination of our future spaces and habits.

The curators created bold, catchy statements that catch your attention and stimulate reflection into how these platforms have influenced our lives, and particularly, our spaces.They used the forum to exhibit dozens of other contributors from around the world across several different mediums, combined with bold graphic statements such as “Access is the New Capital”. “Data is a Relation, Not a Property” and “The Platform is My Boyfriend”, that are literally begging to be posted all over Instagram.

A massive wall primed with various drawings of popular urban features often installed in cities are presented as an “a la carte” catalogue and matched with cheeky descriptions that slightly poke fun at such trends for their ubiquity due to the pervasiveness of these platforms. But it is in that power of humor and arresting statements that bring an otherwise abstract concept into something impactful and digestible along with a cohesive message that can be absorbed through any number of the exhibited offerings.

I had the pleasure of walking through the pavilion with Helge and Peter, as they shared their ideas behind the concept. Please note this was recorded on location at the Biennale, and plenty of organic sounds to accompany the recording.

Peter Mörtenböck, Co-curator of the Austrian Pavilion at the Venice Architecture Biennale in 2021: My name is Peter Mörtenböck, and I'm co-director of the Centre for Global Architecture and a professor of visual culture. I'm really interested in things to do with reality, but also to do with the ways in which we organise ourselves in the world. The network structures, hierarchies, markets, what have you, on the platforms are just one typical form of organisation today.

Helge Mooshammer, Co-curator of the Austrian Pavilion at the Venice Architecture Biennale in 2021: Happy to do so. I'm Helge Mooshammer. I'm one of the directors of the Centre for Global Architecture, which is an initiative that we founded some years ago, which really pursues the aim of providing a platform, speaking of which, to bring together new kinds of research into emerging spatial realities. So when we look around the world, we can actually realise that there are many shared spatial experiences nowadays, and how can we learn from each other when we try to understand these new types of spatial environments? So that's one of the goals of the Centre for Global Architecture. That's the main arena of my work right now.

The title of the party was Platform Austria, and what we talked about—this platform urbanism. So that's just two sentences that are easily said, but what does this actually mean, you know? And can we also show the architectural dimension of that?

So we thought very long and very hard about also the stenography of an exhibition, how to communicate this. And once you delve into the whole complex, coming together with all the different factors that make and constitute the phenomenon platform urbanism, one realizes very quickly that it's indeed enormously complex. So there's so many different layers that all interact and coincide.

So we've realised that we have to start with a very clear message and a message that you cannot escape. When visitors enter the pavilion you need an effective distinction between those two slogans, one about access to new capital, and the other one about the boyfriend. They kind of, again—also there's a meaning which is easy to comprehend, but they are also kind of confusing.

And what we realised is when we also connected this with the topic that Hashim Sarkis has suggested, about thinking about how we will live together, but at the end of the day, architecture is really about very simple things. So it's about providing shelter, it's about providing accommodation, and what shelter does is that it keeps unwanted things away.

We've realised that we have to start with a very clear message and a message that you cannot escape.

In a way, one could also argue that architecture is an intervention in the natural—if we want to say—that flow of things. Whether it's rain, cold, enemies, unwanted people—architecture creates spatial structures that keep these things away from us. So it's also a way, a regulation of access—Who can come? What can come to us? What cannot come? That's one part of it, and the other, in terms of access, and the other half is about, with whom do we want to share this shelter? What community do we want to be with? And what other kind of human people or other entities want to be together? So these are really two very primary questions posed to architecture.

Now, in relation to platform urbanism, what we argue here is that it's still about the same questions, but they are organised in a different way. So digital technologies have now taken over, to some extent, the role that previously very material structures, material infrastructures played, and it's now digital technologies that regulate the flow of things—they regulate access, and by doing so they also become extremely powerful.

So that's very clear. Of course, we might also know about the debates about data, who owns data. There’s a huge struggle about—around digital technologies. The second layer in this stenography of the exhibition is to also point to the fact that even though it's now digital technologies that have taken over the regulation of flows of things, and the kind of guidance and direction is not that this new form of organisation does not also have architectural forms. And what we will see when we come to the site pavilions is that there's actually a whole plethora of new architectural topologies that have emerged, and that influence and shape this new architecture, this new city, these new platform cities.

The question though is, how are these new architectural forms conceived of? It's no longer the classical genius of the sole architect, mostly male architects in the office dreaming up these new forms, and it's no longer the mantra "form follows function". It's different values that shape the new architectural forms. And so what we want to ask is, first, you know, what is it that creates this new architectural form? How do these new architectural forms come into being? And then look at the catalogue of all these different architectural prompts—why do they look like this? What is it that redirects it? And then we've also come to realise that it's all of those new forms of architecture, they're much geared towards fueling the notion of attraction, of making things practical speaking to us, which relates to this intimate aspect of ‘the platform as my boyfriend’ is.

It's no longer the classical genius of the sole architect, mostly male architects in the office dreaming up these new forms, and it's no longer the mantra "form follows function".

The world around us is kind of furnished in such a way to appear attractive to us, so that we are wanting to connect with it. And that has to do with the particular character of platforms, even if we say that these digital technologies of ours have become so powerful, platforms are a particular kind of digital technology. They are a co-produced technology, they're not just working top down, they are relying on our collaboration.

So it's us that make platforms work and make platforms tick. So we need to be drawn in, we need to be seduced. And it's been really interesting also, these two days of the Biennale opening, talking to people and how they also have many kind of other recollections of how this new world that is emerging, always seems to be geared towards creating this promise of this wonderful new world that we want to be part of. And then people say, “Well, why do we?” If we talk about container villages for instance, “Why do we want villages?”, “What's so great about container villages?” I'm sure Prague has one as well. I know a student of ours, and she made this project about the new marketplaces near I think, is it the North, the railway station close to Eastern Railway Station, northeast of, I don't know, but this project of a market?

Alexandra Siebenthal, reSITE: Yes. Actually, it's really funny. So the founder of reSITE founded this market. But we were in—that was one of the things and we were talking, you know, seeing some of the things you have on the wall over there, particularly with the shipping containers. And yeah, like, it was an interesting juxtaposition. Yeah, we’ve done that. But it's something to explore.

Helge: Did you notice how people did want to do that, because it's actually the origin of this new Platform Urbanism is very much grounded in counterculture. Initially platforms were all about these ideas about self-initiating a space, a third space as it were. And so many of these container villages also originated in that. The people said, "Well, how can we create space for ourselves?" And now it's become commercialised. It's become commodified. It's easy to do, you don't need to invest into a real proper quarter for young people, you just say, here you have your containers and be entrepreneurial, do your pop-up shops, do your pop-up restaurant, cafe, and everything will fall into place by itself. It's not always true. So let's just walk through the exhibition a little bit.

Many people have an inclination of what platform urbanism is about, but then it's also very fleeting and ephemeral. It's difficult to pinpoint. And so that's why we've said, well, platforms are really about the creative connections bringing different interests together. And would there be a way that we could experiment ourselves with the potential of a platform, precisely because platforms have this history of actually creating alternatives?

Initially platforms were all about these ideas about self-initiating a space, a third space as it were.

And so we started to invite all these people from around the world, who we know have been working on these issues. So like Susan Moore, and—or those people, Sidovsky, or those who had their staff started to also write about or instigate projects—to go past I think of this station. You can hear podcasts. And so we invited them to blog about their everyday experiences of platform urbanism and they've written about it and they said, "Well, you know, the great thing about the blog is that you don't have to write this kind of scholarly essay, you can just write a short observation, like a diary almost".

And then we've collected those, and we've kind of reworked them into these short video clips. They're not long, each one is not longer than two minutes. You don't necessarily have to start at a particular point, because they're just the colour grading this kaleidoscope of everyday experience, of platform urbanism, but wherever you would start with a little aspect of it, and then it comes together as a bigger picture of what it means.

It's really interesting, so for instance this one, everything in itself is just very small. But this kind of street culture, if you will, has emerged to mark certain areas where you can create—make signs where free WiFi is available. This has a particular expression to think about is a spray painting, but there's a particular expression actually for that, is it true marking or so that you must be like a code? It's like graffiti in particular, but it's like, let me just look for that particular term. It's like, it took like a clandestine code. That's how it emerged, when WiFI was scarce. So people said, "Oh, you know, I make this mark so that others know, oh, there's WiFi". You know, you can get free WiFi here. And so certainly, the world is structured around access to WiFi. Because when we talk about access, of course, it's great to have a platform and apps.

One of the challenges is also that the visible side of platform urbanism is mostly just apps—and there are millions of different apps. But what is an app? I can just pay for the service and it makes things easier, but essentially you need a phone, and you need power so that your phone works. If your phone is dead, you won't have access.

And literally one of the challenges is also that the visible side of platform urbanism is mostly just apps—and there are millions of different apps. But what is an app? I can just pay for the service and it makes things easier, but essentially you need a phone, and you need power so that your phone works. If your phone is dead, you won't have access. So it's as simple as that.

Let's start with these areas that have no connection to the internet, and are cut off from the new kinds of societies. And all that comes together. None of it in itself says the whole story. You cannot tell it in simple [terms], but you need to bring all these different things together. And so that's what’s so great about this very conventional—one could call it the classical gallery of images that are presented like in a gallery of paintings, but they intersect together, they then allow us to understand how all these different sides and how all those are necessary and how they then create this universe of platform urbanism.

Peter: If you stay here for a moment—but I think what really got the thing started about the way in which we want to set up an exhibition about platform urbanism was to think about how new information landscapes are being structured and the way in which we relate to them. Because typically, if you think of a physical landscape, you know how to relate to them, physically, bodily, but also in the way in which we perhaps have an ownership, a certain claim in relation to a particular place, but in relation to digital spaces, and those that are much more dispersed through platforms and technologies.

We have a little sense about our own relationship to those and how we can situate ourselves in this information landscape. And that's the reason why we were thinking about the instruments, the institutions that are currently the curators of that particular information landscape. So platforms are the organiser of public discourse. They are the most concrete example of who is actually curating that kind of landscape.

Platforms are the organiser of public discourse. They are the most concrete example of who is actually curating that kind of landscape.

And so we thought that well, if you organise an exhibition, you have the possibility to intervene in that particular way by also curating knowledge about particular aspects, particular pockets of that landscape. And that's why we're thinking about inviting people, and having them tell us their own experiences about how they relate to particular aspects of platform urbanism—where it started. But we also wanted to connect our thinking to a particular tradition of architectural writing, in terms of blog writing, which is very different from social media nowadays—Twitter and Instagram, those media, which are very much driven by visual performance.

With blogs, that was a much more open-ended way of articulating oneself, say 15 years ago. And so we were inviting some well-known architectural bloggers like Owen Hatherley from the UK, and other people's work. But we wanted to extend the circle to invite as many people as possible coming from different backgrounds—disciplinary backgrounds, generational backgrounds, geographical backgrounds—to collect knowledge from all around the world. So that was the system that informs how to set up this exhibition. And that's why we ended up having 60 different—more than 60 different contributors assembled here in that space.

Alexandra: That's—absolutely, I really liked that about that exhibit, he does create so much more access, you know, just about these different perspectives. And actually, what was really interesting is that both Teddy Cruz and Fonna Forman, as well as Saskia Sassen, have spoken at our events. And so it's nice to see them that you know, you've also drawn a lot of inspiration from their work and kind of contributed to it here.

Helge: Yeah, very much so—and Saskia Sassen is quite the essential voice here. Because one of the questions that often arises is, of course, also that—well, when you have developed this critical view on platform urbanism, a lot of worries emerge. You know—what is happening, what directions are evolving—and Saskia Sassen, then as the kind of grande dame of architectural critique can step in and say yes, all this critique is essential and all this—that's important.

Various access is something that is not a given, access needs to be acquired.

But really, what it's not about is creating this black and white scenario. It's not about that we need to completely oppose the commercial side, as she says, of platform urbanism. That will always be there and it's probably good to have all this is—also the commercial developers that offer us these services. It's just important that there's not just a model for that, in terms of access. It can be a wide range of different providers of access, if you will.

So if we create this monopoly, then we need to start to worry, but you could be good—they could. I think she says literally, different providers could coexist side by side. And it's actually— what's much more difficult, she then continues, is in when we think about these alternatives. Again, there are very established understandings of an alternative format of access, when we think about the clearly underprivileged, they clearly disempower. But there are many in-betweens, those that are often overlooked, that are also underprivileged but are not so clearly visible as being poor, as such. So actually, we need to be much more sophisticated on the side when we think about alternatives. That's not the clear setting. Where we need to get active and where we will need to start thinking about other forms of alternatives.

Alexandra: Maybe what, what are some of the dangers then of really fragmenting access?

Helge: Well, what I mean, one of the key questions, of course, is that access is not a given right. So it's a completely different starting point. In a democratic understanding there are universal human rights that cannot be reduced, that are irreducible. Every human being at the moment one is born, one emerges on planet Earth—there are certain rights that are not, cannot be externalised.

Various access is something that is not a given, access needs to be acquired. And how is it acquired? By becoming legitimised. You need to register, you need to create a profile, you need to become recognisable even, you need to become knowledgeable. So you need to provide certain, whether it's in the form of data or whether it's some form of certain characteristics, certain references that you can provide that you say, "Oh, I'm a citizen of somewhere. I have all this kind of credit that allows me to register, but I need to look for this credit. I need to create it. I need to document it. I need to establish it".

So it's not something—we don't start from a level playing field. And of course, nobody ever does start on a level playing field. In any case, you're born into a particular class, into a caste, a particular gender—categories I ascribe to use. And it's, of course, a long-standing history of unequal access, and you're not denying this. But here, access becomes further complicated, if you will, that you—we need to get active. If you don't get active and if you don't provide the features that you can be recognised as someone who deserves and can be granted access, you've already lost in a certain way.

Access becomes further complicated, if you don't get active and if you don't provide the features that you can be recognised as someone who deserves and can be granted access, you've already lost in a certain way.

You will not be able—and now with of course the pandemic, with all the precautions that are taken in different places, that when you want to move, you need to register, you know, unregistered movement is not possible or is not desired at the moment. All that already illustrates the challenges. If access is regulated by digital technology, which is a database, access is then dependent on the provision of certain sets of data.

And in an analogue city, I mean, in an ideal analogue city, everybody could just enter in public space, and then it would just depend whether you would follow certain rules, certain behaviour regulations. But if you would do that everybody would, theoretically, have the same provisions of access. But here, it's different. It's ready before you even get to the point to enter that space. You need to require the kind of—you need to require the licence, as it were. So you need to become licenced. It's not a matter of rights, but it's a matter of licence.

Peter: The question then was how to transform access from a purely material issue to a political question. And that involves thinking about access, not as restricting access to something and regulating access to something, but offering access and demonstrating a form of generosity, a form of solidarity, and rephrasing—reframing access as a form of friendship, love, but in a sense that it proposes, suggests, and demonstrates some kinds of—also some qualities, that are far beyond the metrics of what the regulation of access typically implies. That you would count how many people would have that kind of particular kinds of access and equal tiers of access, but rather offering access to as many people as there was a population as soon as possible. And that kind of political discussion is currently restrained.

And so, we were thinking, but we are talking about several issues with platforms and how they could be restructured to transform these different questions—the question of access, the question of servicing cities, and how those aspects could be transformed into something else that would make use of platforms in a much more open-ended manner.

Helge: One of the key features of the way access is regulated today is that you need to be active. So activity is a kind of measurement that supports access, so a lot of the new kind of platform architecture is also kind of designed in such a way as to stimulate activities to stimulate circulation, and through that circulation—you know—data noise is created, and that creates crises. So, particularly people who have been inactive are falling out of access categories.

Is there a possibility of simply being a community, rather than constantly having to acquire your belonging through your activity?

So, whether this is because you are not employed in an official way or, you know, you—certain things that you do and don't do the presupposed way, then you're deemed inactive. And so, that question for you know, what does it mean for a society that is based on the aim and the idea of activity? And so, how values are generated purely through activity through being always productive and always active, as you said, and that relates to the question between licences and drives, because licences are something that allow you to do something.

Again, creating activity, where as a right you can also be inactive, you can be in an inoperative community, if you will. So, is there a way that we can simply be? Is there a possibility of simply being a community, rather than constantly having to acquire your belonging through your activity? So I want to continue with the architectural forms because that's what we decided is so important.

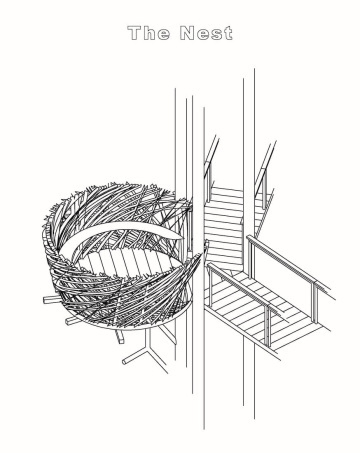

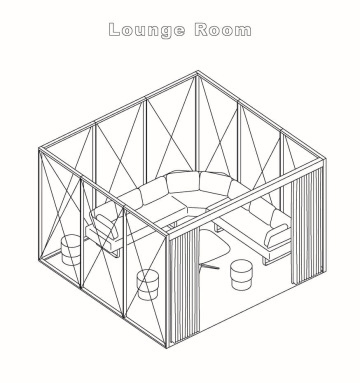

Either way, when we talk about [it], the activity becomes the kind of leading motif of architectural design, what also becomes remarkable is that a lot of the activity is not geared to any particular purpose or any particular function. It's purely for the purpose of activity for its own sake. And so what kind of architecture emerges then if there is no function almost, or as we conventionally understand it. So, what we've done is that we've visited literally hundreds of different locations around the world of this new type of architecture—the container villages that we spoke about, and you will see. But there's a container village, you know, that was in Prague, and then in Vienna, in Amsterdam, but also in this form, and in Las Vegas—all places. And they all reference each other.

So the Las Vegas container villages, you know, says, "Oh, you know, we saw the Brixton container village, and we think that took writing wanted to breathe, reconstructed," then the Abu Dhabi one says, "Oh, you know, this is like the London one," and so they all connect to each other and they legitimise each other by referencing each other. And so what then if you then in the technique of a kind of collage analysis emerges is, if you overlap, and in the same way as platforms decontextualize their architecture also almost decontextualized. But purely creating a kind of scenario is a scene, a stage, a setting of these different architectural expressions, particular kinds of formative and figurative patterns emerge.

And so, all this creates like really, like in a theatre, creates a stage that appears to be very attractive to us. And we then decipher the different props used for setting that stage. And that's what you see over here is this—almost like a catalogue book of new architectural topologies. And you just can browse through the catalogue. It's like a collection of papers and drawings. And you can choose and pick and choose if you will, and often for if you want to have a you know, a young startup environment and being you know, young and trendy and be and remain attractive, I choose from the catalogue in a little bit of...

the activity becomes the kind of leading motif of architectural design, what also becomes remarkable is that a lot of the activity is not geared to any particular purpose or any particular function. It's purely for the purpose of activity for its own sake. And so what kind of architecture emerges then if there is no function almost, or as we conventionally understand it.

We spoke with some people, they said, it's very funny that it's all almost pre-industrial. So, handicraft is very popular at the moment, so everything is retro. And so even if it's a newly built industrial bench, you kind of treat it in such a way that it appears to be old century. In the US, in particular, they call it European farmhouse-style, and all that nonsense. And so you can choose from this and also in an intriguing way these books appear to be scaled.

Headphones are equally important to allow for these co-working environments. For instance, [if] you have no headphones, you cannot use a co-working space. But you also need the coffee stop and the food corner and the food truck with nearby furniture. But how do they relate to each other? Here are some things that are big, some things are small. And they have created a kaleidoscope. And those of the individuals actually often are treated in such a way that particular firms register patents on this.

Because if you have this knowledge, like data knowledge on this, this allows you to become the global provider of let's say, co-working spaces, or co-living developments who create the know-how. It's an architectural know-how that is actually built up through these painted drawings.

But let me just go back to this setting of the scene, because what's of course clear is that this cannot just magically happen by itself. And so as in any theatre, this the stage, but there's the backstage as well and people. There's a lot of labour involved, so there is a real backstage now as well, that helps to create bots on the stage to be seen. And so this is how these two side galleries work together. It's like there's 50 onstage and offstage, and they come together, and we don't see them together. In most cases, we only look at a stage. We don't want to look offstage.

It's not such a nice world for many people. It's the distribution centres to highways. Funnily enough, because we talked about the containers, the containers feature in both worlds. You have the colourful ones here and you have grey ones, the battered ones over there. And so how can we—is there a way to reconcile these different worlds? To not just look at what's on stage, but also to look at what's offstage. And so that's the, I think the provocation articulated in this exhibition is how can we intervene in these two worlds—how they relate to each other. And that's why we have this first slogan at the front. We like that actually, in platform urbanism, it relies on our corporate action, and we can intervene in our imagination.

And so if we continue to, kind of, well, he will show me today is given in the condition. That condition can only be like image fangirls, which is a very simple proposition—is the world how we think about it, is really, also relies on images, particularly in a mediated world, like in a platform world. So if we intervene in the way we imagine things, we might also be able to think about these things differently. And so platforms with the sense of the notion of co-production, allows also to collectively co-produce imaginary.

Okay, so we invited people to simply post photographs that were taken with the phones of any everyday situation, and post those and then you collect them. And then similarly, perhaps first like we did with the colleges—to design a new architectural language, a pattern language, if you will, to go back to architectural history. A pattern language of a new platform urbanism that emerges might look very different if you know, different kinds of containers might be, you know, populating this new brave world? So, it's really interesting.

I mean, we've only just started, it's very early days. But again, people are posting lots of areas that you really appreciate. Yeah, it's really interesting to see what emerges in the centres of interaction and in these different ways in which we position this kind of indication, next to the slogan of data is a relation of the property, because I think that's really the way to not just..

What's the chamfer that not to say, “Oh, you know, platforms are all negative, you know, that we don't want platforms”. But platforms have a history of bottom-up initiative. And one of the things to recuperate, that is also to start to reframe, and that's what an art exhibition on architecture exhibition can do, it can reframe certain connotations, through representations. And the reframing of data is really important because data now we only think about data in terms of property.

And of course, property in English has this double connotation that it means characteristics. And it also means commodities that can be traded. But it's apparently only a small step from property as characteristic to property as commodity, as something that can be traded. But instead of really a property or characteristic, or isn't data actually something that we as humanity create as a navigation tool, to help us navigate the way we interact and how we coexist? So we have like, it's, you could call it a grid of reference, a reference grid, if you will, that helps us to deal with each other. So if I know where X-epsilon is moving from A to B, then that's not just that's not a characteristic of them. But I create data about this movement in order to be able to relate to that. So it's actually about the relationship.

And the big step forward when thinking about data as a reference is that then it's not a characteristic. And it's also not the property that is owned by a sole entity or sole person, but their relationship always depends on two sides. And it's actually collectively or public cooperatives. So data is not owned by individuals, but data is always owned by those entities involved in that exchange, those entities that want to know each other. And so that opens up a whole new path around—to think about platform urbanism completely differently.

Alexandra: It's really incredible. I really like how you're turning the tide, and how we are thinking about it, looking at it, and I think it's really important, and it was a very, very timely conversation.

Helge: So the big question is, of course, does it work when you present it in such a way? But we are really interested in hijacking the platform city. So to [make] this Instagrammable, the exhibition is very Instagrammable.

Alexandra: I'm guilty of Instagramming it.

Helge: No, but it's important because then you can intervene. You can distribute a message in a different way. And you talked about this Biennale as being a Biennale of messages. And you know, I very much support Hashim Sarkis' stance that the Biennale needs to take on this role of being an ambassador. It's so important that the Biennale is not just saying, "Oh, you know, we are just indulging [in] each other, and look at us—what great things we do". But we take a stand. And we say, "Well, you know, architecture is interested in making this a better world". And we can do that together, we can do that.

And to be such an ambassador, you need to have a message. And so that's how the whole list can tie in, creating these representations of messages, that if people like to take a photograph, this is brilliant. And then he can replicate. And yes, and suddenly people can say this sentence, it creates a vocabulary. And he creates a collective vocabulary that everybody can, not everybody. But some people can say, "Well, I don't think data is a property, you know, it should not treat data as property that gets traded. And I'm not happy if somebody just simply pays me for my data, I want to be understood as something that is actually common goods, it's a commons data is a commons. And now it's not an individual property, you know, it's not a capitalist commodity, per se."

It has been turned into a capitalist commodity, but this involved many different steps to actually frame it as property is not a breakeven. It starts with framing us as individuals as being possessive individuals that all have certain characteristics that we own. But even that was a first step. You know, it's again, not a given that we understand ourselves as separate individuals with each individual having particular individual properties, you know, that's already, you know, a way of distinguishing between human beings. That's not the breakeven. And so I think this is very important to create this vocabulary.

Alexandra: I think you're doing it well, and I you know, to me, I think that's why this ended up being one of my favourite pavilions/installations, because it is so powerful in the way you presented it and just making statements that—yes, yes, but actually one of my favourite parts of it and my colleague here, we were laughing at it.

Helge: If you don't like it, we don't love our army, but we love...ya know, that's that? I definitely see that many people have, you know, respond that way, and that's really great to see, because at the end of the day, culture is also somebody that needs to be experienced, you know, this is a cultural event. But it's us as human beings—we spend our time, you know, we go through and also that counts as well. We're not just an abstract machine for this exhibition. So how do we experience it? This is also providing some pleasure. That's important, I think.

And I think also some of the pavilions do this really brilliantly that they provide with—said the kind of culture—was it the senses—the central experience. Whether it's visual, or that's true in tactile senses, or for audio when you walk through. And I think that's very important. That's what an exhibition can do. So, you know, you're sure you have your opinions about those pavilions and then also central.

Alexandra: No, I like it when there's just one clear message that you can walk away with. And there's just so many different applications of it. So if you don't understand one thing, there's another way you kind of get it.

Helge: So it's very distributed. Yeah.

Alexandra: And I think there was, you know, there's tons of little gems here.

Helge: Yeah, about the layering.

Alexandra: Maybe a more personal question, is there an app you, either of you, spend time on yourselves?

Helge: Well, very simple ones, really, in terms of when we talk about navigation, I think navigation tools as navigation apps, are ones that people use in particular. So I'm not really guilty, but simply using Google Maps as an app is presumably a common one.

Apps are created and investment is undertaken, but then this app disappears very quickly. And what's the—what about the people involved in that, you know, people work for that—their services are offered on a platform. And so if you had a look at that book, and I'm not sure whether you had time to read it, but the introduction, we write about platforms as kind of member clubs, so we compare them to a club, like an old fashioned British club almost. And so when you register, you become a member of that club, and your livelihood is tied to that club. But what happens is so many other providers and other partners change their provider, suddenly, you're excluded, because you're on the wrong app, and you're in the wrong. So to think about how, without actually using a version, but it's good.

Alexandra: It's very true. So question, what do you think we will be, you know, every era has a type of monument, or, you know, era of design, let's say. What do you think? What will our monument be for this moment in time? Shipping containers?

Helge: I suppose we have—we actually structured the contribution of lockers in seven different chapters. And in one of the chapters, there's the title, "Monuments of Circulation: I is Everywhere." And so I think the question is really, I suppose the monuments of our time are atomized monuments, and they are documentations of our own circulation. So we are acting, we're alive because we circulate. So it's all these Instagrams, it's all these little fictions of us, of "I". So it's really the "monument of I."

So, what is the Biennale for, if not to influence and provide access to new ideas and ways of viewing architecture and spaces we share. The curation behind both Austrian and British pavilions share a common thread of accessibility. Their immersive interventions help the viewer experience what accessibility means and question the limits. The installations communicate in a way that is comprehensible to a wider audience—all while being visually very appealing.

I would like to personally, and on behalf of reSITE, thank you all for tuning in, for taking this journey with us as we navigate building a podcast in the midst of a pandemic. After this episode we will be taking a summer break for the coming months, and returning in autumn 2021 with a bigger, better and longer season 3.

We have loved getting to create this podcast, and we hope you’ve been enjoying it just as much. Reaching a new audience, on a new platform with the same mission—elevating people and ideas to improve the urban environment—in the middle of a pandemic has been what we feel to be an important action. Also important to us is that these ideas remain accessible and free.

As a nonprofit, we are only able to produce this podcast thanks to the generous support of the City of Prague, the Czech Ministry of Culture, corporate sponsors, private philanthropists, and our network of passionate architecture and city lovers, like you. If you would like to support us as a patron, sponsor or strategic partner, please get in touch with us at podcast@resite.org. Your support allows us to continue sharing ideas to inspire more livable, lovable cities.

This episode was directed and produced by myself, Alexandra Siebenthal and Radka Ondrackova and with support from Martin Barry, Nikkolas Zellers, Weronika Koleda, and Anna Stava, as well as Nano Energies and the Czech Ministry of Culture. It was edited by LittleBig Studio.

More Venice Biennale curators featured in this episode:

Venice Architecture Biennale Nordic Pavilion: What We Share with Siv Helene Stangeland + Reinhard Kropf

reSITE is back with a special two-part Design and the City episode covering the long-awaited Venice Architecture Biennale to explore the question “How will we live together?” We spoke with exhibitors of the Nordic Pavilion, Siv Helene Stangeland and Reinhard Kropf, entitled What We Share about the inspiration behind their co-living experiment in Stavanger, Norway, which they not only designed, but also occupy, along with 65 other tenants.

Venice Architecture Biennale U.S. Pavilion: American Framing with Paul Andersen + Paul Preissner

reSITE is back with a special two-part Design and the City episode covering the long-awaited Venice Architecture Biennale to explore the question “How will we live together?” Part-one covers the U.S, Pavilion curators, Paul Andersen and Paul Preissner as they reexamine humble softwoods and their place as the literal bones for American homes in their exhibition entitled “American Framing”.

Venice Architecture Biennale: How Will We Live Together? [Part 1]

reSITE is back with a special two-part Design and the City episode covering the long-awaited Venice Architecture Biennale to explore the question “How will we live together?” Part-one covers the U.S, Nordic and Luxembourg Pavilion curators for their use of timber and wood construction to answer this years pressing question.

Venice Architecture Biennale: There Are Walls That Want to Prowl, Lukas Feireiss + Leopold Banchini

reSITE is back with a special two-part Design and the City episode covering the long-awaited Venice Architecture Biennale to explore the question “How will we live together?” with curators Lukas Feireiss and Leopold Banchini to discuss their definitions of shelter, application of wood structures, degrowth models and retrospectives to rethink how we will live together.

More from Design and the City

Trey Trahan on Building Sacred Spaces for Connection

This episode of Design and the City features the founder of Trahan Architects, Trey Trahan on the importance of creating sacred spaces devoid of clutter that make way for that human connection, his definition of beauty, and the potential regeneration holds, presenting a different side of that coin.

Tim Gill on Building Child-Friendly Cities

A city that is good for children, is good for everyone--and idea we explore with Tim Gill, author of Urban Playground: How Child-Friendly Planning and Design Can Save Cities, on this episode of Design and the City. Photo by Els Lena Eeckhout.

Why is Birth a Design Problem with Kim Holden

Can rethinking and redesigning the ways birth is approached shift the outcomes of labor and birth experiences? Can it be instrumental in improving our qualities of life--in our environments, in cities, and beyond? Architect and founder of Doula x Design Kim Holden join Design and the City to explore how she sees birth as a design problem. Photo by Kate Carlton Photography

The Architecture of Healing with Michael Green + Natalie Telewiak

Michael Green and Natalie Telewiak love wood. These Vancouver-based architects champion the idea that Earth can, and should, grow our buildings--or grow the materials we use to build them on this episode of Design and the City. Photo courtesy of Ema Peter