Abstract

Objective

The purpose of this study was to explore personal and organizational factors that contribute to burnout and moral distress in a Canadian academic intensive care unit (ICU) healthcare team. Both of these issues have a significant impact on healthcare providers, their families, and the quality of patient care. These themes will be used to design interventions to build team resilience.

Methods

This is a qualitative study using focus groups to elicit a better understanding of stakeholder perspectives on burnout and moral distress in the ICU team environment. Thematic analysis of transcripts from focus groups with registered intensive care nurses (RNs), respiratory therapists (RTs), and physicians (MDs) considered causes of burnout and moral distress, its impact, coping strategies, as well as suggestions to build resilience.

Results

Six focus groups, each with four to eight participants, were conducted. A total of 35 participants (six MDs, 21 RNs, and eight RTs) represented 43% of the MDs, 18.8% of the RNs, and 20.0% of the RTs. Themes were concordant between the professions and included: 1) organizational issues, 2) exposure to high-intensity situations, and 3) poor team experiences. Participants reported negative impacts on emotional and physical well-being, family dynamics, and patient care. Suggestions to build resilience were categorized into the three main themes: organizational issues, exposure to high intensity situations, and poor team experiences.

Conclusions

Intensive care unit team members described their experiences with moral distress and burnout, and suggested ways to build resilience in the workplace. Experiences and suggestions were similar between the interdisciplinary teams.

Résumé

Objectif

L’objectif de cette étude était d’explorer les facteurs personnels et organisationnels contribuant à l’épuisement professionnel et à la détresse morale dans une équipe de soins de santé d’une unité de soins intensifs (USI) universitaire canadienne. Ces deux problèmes ont un impact significatif sur les fournisseurs de soins de santé, sur leurs familles, et sur la qualité des soins aux patients. Ces thèmes seront utilisés pour concevoir des interventions afin de développer la résilience d’équipe.

Méthode

Nous avons réalisé une étude qualitative utilisant des groupes de réflexion afin de mieux comprendre les perspectives des personnes concernées par l’épuisement professionnel et la détresse morale dans l’environnement des équipes d’USI. L’analyse thématique des transcriptions des groupes de réflexion, composés d’infirmières et infirmiers, d’inhalothérapeutes et de médecins intensivistes, prenait en considération les causes d’épuisement professionnel et de détresse morale, leur impact, les stratégies d’adaptation, ainsi que les suggestions pour développer la résilience.

Résultats

Six groupes de réflexion, chacun comptant quatre à huit participants, ont été créés. Au total, 35 participants (six médecins, 21 infirmières et infirmiers, et huit inhalothérapeutes), représentant 43 % des médecins, 18,8 % des infirmières et infirmiers, et 20,0 % des inhalothérapeutes, ont pris part à nos groupes de réflexion. Les thèmes concordaient entre les professions et comprenaient : 1) les problèmes organisationnels, 2) l’exposition à des situations de stress élevé, et 3) les mauvaises expériences d’équipe. Les participants ont rapporté des impacts négatifs sur leur bien-être émotionnel et physique, les dynamiques familiales, et les soins aux patients. Les suggestions pour développer la résilience étaient catégorisées en trois thèmes principaux : problèmes organisationnels, exposition à des situations de stress élevé, et mauvaises expériences d’équipe.

Conclusion

Les membres des équipes de l’unité de soins intensifs ont décrit leurs expériences en ce qui a trait à la détresse morale et à l’épuisement professionnel, et suggéré des façons de développer la résilience sur le lieu de travail. Les expériences et suggestions étaient similaires dans les différentes équipes interdisciplinaires.

Similar content being viewed by others

In 2016, the American Association of Critical Care Nurses, the American College of Chest Physicians, the American Thoracic Society, and the Society of Critical Care Medicine published a “Call to Action” in an effort to bring attention to the issue of burnout syndrome (BOS).1 Since then, numerous studies have shown that BOS is widely prevalent in almost all areas of healthcare.

Burnout is defined as a combination of emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and a low sense of personal accomplishment.2 Burnout has significant implications for healthcare providers’, patients, and the organization. Literature indicates that healthcare professionals with BOS have higher rates of substance abuse, broken relationships, depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, and suicide.3,4,5 In the workplace, BOS has been tied to lower quality of patient care, increased patient dissatisfaction, increased medical errors, decreased productivity, poor team morale, and increased healthcare provider turnover. 6,7,8,9

Moral distress is believed to occur when individuals are placed in situations that are at odds with their core values and beliefs and that they have little power to change.10 Definitions in the literature often draw attention to key components such as complicity in wrongdoing, lack of voice, and wrongdoing associated with an organization’s professional values and practices.10,11,12,13,14 It is this pressure to act unethically that defines the phenomenon. A positive correlation between burnout and moral distress has been reported.15,16,17

Previous research quantified high rates of burnout and moral distress in the same ICU team.18 High and moderate levels of emotional exhaustion were 27.3% and 39.4%, respectively. Depersonalization was high in 13.9% and moderate in 33.3%. Low personal accomplishment was experienced by 27.9%, with a further 37.0% experiencing moderate personal accomplishment. 55.2% of participants reported moral distress at least a few times a month and 29.9% reported it at least once a week. Although the study used the Maslach Burnout Inventory,19 a well-validated measurement tool for BOS, it lacked in-depth exploration of possible contributors to burnout and moral distress in the team.

The purpose of this qualitative study was to explore in detail the factors, both at the individual and organizational level, that were contributing to burnout and moral distress in the healthcare team at the NSHA- Queen Elizabeth II Health Sciences Centre (QEII HSC) ICU, Halifax, Nova Scotia.

Methodology

Design and participant selection

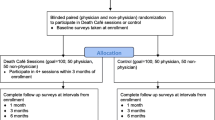

Research Ethics Board approval was obtained in January 2019 (REB File #1024175). We used focus group methodology to elicit a qualitative stream of data to better understand issues related to BOS from a stakeholder-centred perspective as they react to and build on each other’s observations, perceptions, and thought processes.20 Participation was open to all registered intensive care nurses (RNs), respiratory therapists (RTs) and physicians working in the NSHA- Queen Elizabeth II Health Sciences Centre (QEII HSC) ICU. This ICU is closed and composed of two units; a 12-bed neuro-medical-surgical-trauma ICU with staff rotation through both sites. Staff were made aware of the study through departmental interprofessional presentations and study information displayed throughout the ICU. Focus group recruitment was by voluntary sign up on a first come, first serve basis until the focus groups were filled.

Written informed consent was obtained prior to the start of the focus groups. Study design consisted of six focus groups with four to eight participants per focus group. Given the ICU dynamics and psychologic safety of participants, groups were identified by professional designation. This included one physician group, one RT group, and four RN groups.

Focus group interview guide preparation

The focus group interview guide (eAppendix A in the Electronic Supplementary Material [ESM]) underwent iterative review and explored the daily work environment at both an organizational and individual level. It probed situations that contributed to burnout and moral distress, team dynamics, strategies currently used to cope with work stress, and interventions the participants thought helped build resilience. Standard definitions of burnout and moral distress were included in the interview guide and posted in the room during the focus group sessions (eAppendix B in the ESM). The facilitator of the focus groups was a university faculty member experienced in facilitating focus groups and was not connected to the ICU team.

Data analysis

A thematic analytic approach was used to guide analysis of the data.21 Thematic analysis is a six-part step-by-step technique to analyzing qualitative data that identifies themes and patterns, and generates rich description.

All focus groups were audiotaped; transcribed verbatim and field notes added contextual data. Qualitative software, Quirkos (www.quirkos.com), accommodated the storing, sorting, indexing, and coding of all data. Research team members independently read and reread each transcript and developed initial codes across the entire data set. Coding was largely an inductive or bottom-up activity. We compared the codes within the research team and resolved any differences through consensus. We then collected the codes according to potential themes. Themes were reviewed and a thematic analytic map was generated, followed by defining and naming the themes. Themes distilled were compared and contrasted between the key stakeholder groups. Finally, we produced a report and extracted compelling examples, and related our findings to the literature and research questions.

Results

Participant demographics

Thirty-five healthcare workers participated in total: six MDs, 21 RNs, and eight RTs. This represents 43% of the MDs, 18.8% of the RNs, and 20% of the RTs who work in the ICUs. The focus groups were primarily female (85.7%), with the exception of the physician group, which was predominately male (83.3%). All levels of work experience from junior to senior were well represented: 37.1% of participants had worked 0-5 years, 31.4% had worked 6-15 years, and 31.4% had worked 16+ years.

Burnout and moral distress

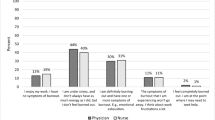

Although coding and thematic development were independent for both moral distress and burnout, three common themes emerged from both. The three overarching themes were organizational issues, exposure to high intensity situations, and poor team experiences, and these were further subdivided into subthemes (Figure). Quotes supporting each of the themes can be found in eTable 1 and eTable 2 in the ESM. Although these major themes emerged from all health professional groups, there was some variation in how they presented between groups.

Organizational subthemes included a lack of adequate physical resources, lack of adequate staffing, ineffective organizational policies, and disengaged administration. Decisions made by the health organization were often viewed to be at the expense of quality patient care or the physical and/or mental health of its employees. Within the organizational subthemes, there were some differences between health professions with respect to ineffective organizational policies. For example, in the physician focus group this included policies around bed management; however, nursing and respiratory therapy focus groups discussed policy inefficiencies regarding staff education.

Exposure to high intensity situations were described as contributing to both moral distress and burnout. The subthemes within this category included provision of futile care and end of life care, advocating for appropriate patient care, the healthcare provider-patient/family relationship, and workplace violence. While futile care, end of life care, and advocating for patient care were common to all professions, in this study, the complexity of patient and family relationships as well as workplace violence were unique to the nursing profession. Provision of futile care was the most frequently described situation causing both burnout and moral distress. Perceived futility of care was described as stemming from the medical team (any healthcare provider within the patient’s circle of care) and/or family who are not prepared to stop treatment. When the interdisciplinary team members have different beliefs on the level of treatment to be offered, it was reported to have a negative impact on both individual and team dynamics.

With respect to both burnout and moral distress, poor team experience subthemes included lack of control in the workplace, lack of appreciation by team members and administration, fragmented patient care, and negative team dynamics. Negative team dynamics comprised poor communication, lack of trust and respect, bullying, and lack of inclusion. Lack of inclusion in the team was unique to the respiratory therapy focus group and was only reported as a cause for burnout, not moral distress.

Significant overlap between the situations causing burnout and moral distress was noted. An example of this overlap is shown in the discussions regarding the need to advocate for appropriate patient care. In this example, clinicians described moral conflict when providing treatments they deemed to be outside of the patient’s stated wishes and feeling internal constraints to voice these concerns. Participants also described emotional exhaustion, a low sense of personal accomplishment, and detachment from the patient and families in these situations.

The impact of burnout and moral distress

Our data shows that the impact of working when facing burnout and moral distress is far reaching. Healthcare professionals reported a physical and emotional toll, impact on their family and home life, and a decrease in compassionate patient care. Many of these experiences elicited strong, negative emotional reactions such as anger, frustration, anxiety, fear, defeat, and demoralization in the healthcare provider (eTable 3 in the ESM). Often, these emotional experiences manifest themselves physically as overwhelming exhaustion. Along with the emotional toll, working in the ICU has a significant physical toll on the provider. Participants’ shared many stories about work-related injuries, physical exhaustion, and self-sacrifice.

The inability to leave work behind at the end of the shift was a common theme among nurses and RTs. This often had an impact on family dynamics; either in the form of isolation from loved ones or in the need for connection due to fear and anxiety of something bad happening. Universally, these experiences were felt to negatively impact the quality of delivered patient care in terms of loss of empathy and compassion. This in turn increased guilt experienced by the healthcare provider.

Coping strategies

Focus group participants were asked to provide examples of strategies for coping with workplace stressors both within and outside the workplace. Described strategies were both self-constructive and self-destructive. For example, excessive alcohol consumption is a self-destructive behaviour, while exercise is a self-constructive behaviour (Table).

Building resilience

Participants were asked to suggest interventions for building resilience. These suggestions are shown below and are organized by the three common themes identified as causing burnout and moral distress.

-

Organizational: improving staffing, investing in healthcare provider education, improving existing infrastructure, and adding new infrastructure.

-

Exposure to high intensity situations: regular debriefing sessions, destigmatizing the need for support, mental health wellness days, long-term follow-up on chronic patients that have left the ICU, addressing workplace violence.

-

Poor team experiences: inter- and intra-professional relationship building, teaching respectful communication and behaviours, acknowledgement of hard work and a job well done, supporting a just culture, hospital leadership engagement, and management support.

Discussion

In this study, three common themes emerged from the burnout and moral distress questions: 1) organizational issues, 2) exposure to high intensity situations, and 3) poor team experiences. In addition, an overlapping relationship was noted between situations that caused moral distress and burnout. The overlap between causes of burnout and moral distress is not unique to our study. In 2017, a survey of more than 200 ICU healthcare providers showed that moral distress, in particular due to provision of futile care, is significantly associated with the development of BOS.15 Similarly, two Canadian critical care studies also found an overlap in contributing factors.16,17

Prior studies have identified organizational issues like process inefficiencies, unbalanced workloads, and unsupportive organizational cultures/climates as a cause of burnout and moral distress. Organizational leadership has also been shown to have a significant impact on healthcare provider burnout, moral distress, and job satisfaction.22,23,24,25,26,27 Similar to sentiments expressed by our participants, a study of US healthcare professionals showed that much of the distress and dissatisfaction related to organizational issues came from the belief that these issues were negatively impacting quality patient care.28

Exposure to high intensity situations like end of life care and the provision of futile care were reported by all participants as a cause of burnout and moral distress, lending support to prior publications.6,15,25,29,30,31 Within our team, this impact came from the amount of exposure to death and dying, as well as situations in which there were discrepant expectations in escalation of care. Discrepant expectations were reported not only between the team and a patient’s family or surrogate decision maker but also within the team as well. These differences in care plans have been previously described as a source of moral distress, workplace dissatisfaction, and burnout,16,29,30,31,32,33,34 further emphasizing the need for communication and relationship building when considering strategies to build resilience.

A consistent theme throughout all focus groups was the magnitude of exposure to tragedy and grief in the ICU. Many participants described feeling isolated as family and friends are not able to comprehend a typical workday and the need for regular formal debriefing sessions was advocated for. Studies on the impact of debriefing interventions on psychologic well-being are mixed. Similar to our results, the request for debriefing sessions and greater psychologic support has been identified in other studies of intensive care health professionals.35,36 Although there were no objective measures of psychologic impact, two studies reported that attending debriefing sessions and talking with colleagues were independently associated with a reduced risk of burnout and enhanced resilience.37,38 In 2018, Browning illustrated a decrease in moral distress in ICU nurses when debriefing sessions were provided on a regular basis over a six month interval. At the end of the study period, 100% of participants requested that sessions continue.39 Conversely, a 2018 meta-analysis of ten studies exploring the effects of post-disaster psychologic interventions included three studies that suggested debriefings can have long-term positive effects with respect to depression, anxiety, substance abuse and PTSD,40,41,42 and seven studies that showed no difference.43

Many important subthemes emerged in relation to poor team experiences contributing to burnout and moral distress; the largest contributor was negative team dynamics in the form of hostility in the workplace, toxic personalities, lack of inclusion in the team environment, lack of respect, poor communication, as well as shaming and bullying. A recent review by Smith et al. described effective teamwork as needing several key features, including: 1) psychologic safety: the team members’ ability to trust one another and feel safe enough within the team to admit a mistake, ask a question, offer new data, or try a new skill without fear of embarrassment or punishment and 2) the ability for team members to learn, teach, communicate, reason, think together, and achieve shared goals, irrespective of their individual positions or status outside the team.44 Psychologic safety was particularly relevant to our focus groups participants as they often expressed a desire for their experiences of shame and fear related to errors to be replaced by a philosophy of just culture within the organization. Research into negative team dynamics has shown a significant impact on job satisfaction, burnout, and moral distress.11,25,45,46 Equally important, the reverse also holds true. Positive team interactions can help improve workplace satisfaction, mitigate burnout, and build resilience.45,47,48,49,50 This suggests that investing in strategies to improve team dynamics would be a useful way for the organization and ICU leadership to build resilience among their workers.

Lack of appreciation was a common theme for all focus groups and was felt from all levels of hospital administration. The form of appreciation desired was often simple, such as an in-person thank-you or acknowledgements of positive achievements. Similar experiences are described in the literature as contributing to burnout in the healthcare team, while attending to these deficiencies helps alleviate stress and build resilience.16,24

This study affirmed previous data that burnout and moral distress are significant issues within this ICU team,18 and taught us about the root causes through exploring everyday work. Strengthening our thematic analysis, the research group consisted of a multidisciplinary team, reducing bias in the interpretation of results. Our results are also strengthened by numerous other publications that have reported similar causes for workplace burnout and moral distress. There may have been confirmation bias in the focus group members, which may have led to an overestimation of the problem. Nevertheless, based on our previous ICU study that had a high percentage participation, we do not think that this is a relevant problem.18 Another potential weakness is that participants may not represent the opinion of the majority of the ICU team as the focus group enrollment was self-selected. Since many of the themes were similar across different professional groups, we do not feel this to be the case. Instead, it gives our study internal validity. Finally, it should also be acknowledged that differences between the groups may not reflect true differences, but may reflect the organic nature of focus group conversations. The facilitator was provided with a guide of key questions, not questions pertaining to specific interventions or problems.

Conclusions

Findings in the data were consistent. Working in an environment of burnout and low morale impacts the physical and mental health of healthcare providers, their relationships with friends and families, and the care of patients. There were many worthy suggestions identified by participants for building resilience in the three domains that contribute to burnout and moral distress, some of which are supported by the literature. Some examples include debriefing sessions, long-term follow-up on ICU patients with positive outcomes, fostering a positive team environment that is supportive and collegial, and encouraging re-engagement of hospital leadership. Implementation and evaluation of the impact of these interventions will be the basis of future work.

References

Moss M, Good V, Gozal D, Kleinpell R, Sessler CN. An official Critical Care Societies collaborative statement. Crit Care Med 2016; 44: 1414-21.

Maslach C, Jackson S. Maslach Burnout Inventory Manual. Research ed. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1981 .

Dyrbye LN, Thomas MR, Massie FS, et al. Burnout and suicidal ideation among U.S. medical students. Ann Intern Med 2008; 149: 334-41.

Mealer M, Burnham E, Goode C, Rothbaum B, Moss M. The prevalence and impact of post traumatic stress disorder and burnout syndrome in nurses. Depress Anxiety 2009; 26: 1118-26.

Oreskovich M, Shanafelt T, Dyrbye LN, et al. The prevalence of substance use disorders in American physicians. Am J Addict 2015; 24: 30-8.

Poghosyan L, Clarke SP, Finlayson M, Aiken LH. Nurse burnout and quality of care: cross-national investigation in six countries. Res Nurs Health 2010; 33: 288-98.

Shanafelt TD, Balch CM, Bechamps G, et al. Burnout and medical errors among American surgeons. Ann Surg 2010; 251: 995-1000.

Shoorideh FA, Ashktorab T, Yaghmaei F, Alavi Majd H. Relationship between ICU nurses’ moral distress with burnout and anticipated turnover. Nurs Ethics 2014; 22: 64-76.

Ackerman AD. Retention of critical care staff. Crit Care Med 1993; 21(9 Suppl): S394-5.

Jameton A. Nursing practice. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall; 1984 .

Bruce CR, Miller SM, Zimmerman JL. A qualitative study exploring moral distress in the ICU team: the importance of unit functionality and intrateam dynamics. Crit Care Med 2015; 43: 823-31.

Varcoe C, Pauly B, Storch J, Newton L, Makaroff K. Nurses’ perceptions of and responses to morally distressing situations. Nurs Ethics 2012; 19: 488-500.

McCarthy J, Monteverde S. The standard account of moral distress and why we should keep it. HEC Forum 2018; 30: 319-28.

Penny NH, Bires SJ, Bonn EA, Dockery AN, Pettit NL. Moral distress scale for occupational therapists: part 1. Instrument development and content validity. Am J Occup Ther 2016; DOI: https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2015.018358.

Fumis RR, Junqueira Amarante GA, de Fátima Nascimento A, Vieira Junior JM. Moral distress and its contribution to the development of burnout syndrome among critical care providers. Ann Intensive Care 2017; DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13613-017-0293-2.

Johnson-Coyle L, Opgenorth D, Bellows M, Dhaliwal J, Richardson-Carr S, Bagshaw S. Moral distress and burnout among cardiovascular surgery intensive care unit healthcare professionals: a prospective cross-sectional survey. Can J Crit Care Nurs 2017; 27: 27-36.

Larson CP, Dryden-Palmer KD, Gibbons C, Parshuram CS. Moral distress in PICU and neonatal ICU practitioners: a cross-sectional evaluation. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2017; 18: e318-26.

Hancock J, Hall R, Flowerdew G. Burnout in the intensive care unit: it’s a team problem. Can J Anesth 2019; 66: 472-3.

Maslach C, Jackson SE, Leiter M. The Maslach Burnout Inventory. 3rd ed. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1996 .

Liamputtong P. Focus Group Methodology: Principles and Practice. London: Sage; 2011 .

Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 2006; 3: 77-101.

McHugh MD, Kutney-Lee A, Cimiotti JP, Sloane DM, Aiken LH. Nurses’ widespread job dissatisfaction, burnout, and frustration with health benefits signal problems for patient care. Health Aff (Millwood) 2011; 30: 202-10.

Shanafelt T, Dyrbye L, Sinsky C, et al. Relationship between clerical burden and characteristics of the electronic environment with physician burnout and professional satisfaction. Mayo Clin Proc 2016; 91: 836-48.

Shanafelt T, Gorringe G, Menaker R, et al. Impact of organizational leadership on physician burnout and satisfaction. Mayo Clin Proc 2015; 90: 432-40.

Dodek PM, Norena M, Ayas N, Wong H. Moral distress is associated with general workplace distress in intensive care unit personnel. J Crit Care 2019; 50: 122-5.

Aiken L, Clarke SP, Sloane DM, Sochalski J, Silber JH. Hospital nurse staffing and patient mortality, nurse burnout, and job dissatisfaction. JAMA 2002; 288: 1987-93.

Friedberg MW, Chen PG, Van Busum KR, et al. Factors affecting physician professional satisfaction and their implications for patient care, health systems, and health policy. Available from URL: https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/research_reports/RR400/RR439/RAND_RR439.pdf (accessed June 2020).

Whitehead PB, Herbertson RK, Hamric AB, Epstein EG, Fisher JM. Moral distress among healthcare professionals: report of an institution-wide survey. J Nurs Scholarsh 2014; 47: 117-25.

Henrich NJ, Dodek PM, Alden L, Keenan SP, Reynolds S, Rodney P. Causes of moral distress in the intensive care unit: a qualitative study. J Crit Care 2016; 35: 57-62.

Hamric AB, Blackhall LJ. Nurse-physician perspectives on the care of dying patients in intensive care units: collaboration, moral distress, and ethical climate. Crit Care Med 2007; 35: 422-9.

Breen CM, Abernethy AP, Abbott KH, Tulsky JA. Conflict associated with decisions to limit life-sustaining treatment in intensive care units. J Gen Intern Med 2001; 16: 283-9.

Salem A. Critical care nurses’ perceptions of ethical distresses and workplace stressors in the intensive care units. Int J Nurs Educ 2015; DOI: https://doi.org/10.5958/0974-9357.2015.00082.3.

Ferrand E, Lemaire F, Regnier B, et al. Discrepancies between perceptions by physicians and nursing staff of intensive care unit end-of-life decisions. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2003; 167: 1310-5.

Papathanassoglou ED, Karanikola M, Kalafati MN, Giannakopoulou M, Lemonidou C, Albarran J. Professional autonomy, collaboration with physicians, and moral distress among European intensive care nurses. Am J Crit Care 2012; 21: e41-52.

French-O’Carroll R, Feeley T, Crowe S, Doherty EM. Grief reactions and coping strategies of trainee doctors working in paediatric intensive care. Br J Anaesth 2019; 123: P74-80.

Kaur AP, Levinson AT, Monteiro JF, Carino GP. The impact of errors on healthcare professionals in the critical care setting. J Crit Care 2019; 52: 16-21.

Watson AG, Saggar V, MacDowell C, McCoy JV. Self-reported modifying effects of resilience factors on perceptions of workload, patient outcomes, and burnout in physician-attendees of an international emergency medicine conference. Psychol Health Med 2019; 24: 1220-34.

Colville G, Smith J, Brierley J, et al. Coping with staff burnout and work-related posttraumatic stress in intensive care. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2017; 18: e267-73.

Browning ED, Cruz JS. Reflective debriefing: a social work intervention addressing moral distress among ICU nurses. J Soc Work End Life Palliat Care 2018; 14: 44-72.

Boscarino JA, Adams RE, Figley CR. A prospective cohort study of the effectiveness of employer-sponsored crisis interventions after a major disaster. Int J Emerg Ment Health 2005; 7: 9-22.

Boscarino JA, Adams RE, Foa EB, Landrigan PJ. A propensity score analysis of brief worksite crisis interventions after the World Trade Center disaster: implications for intervention and research. Med Care 2006; 44: 454-62.

Tehrani N, Walpole O, Berriman J, Reilly J. A special courage: dealing with the Paddington rail crash. Occup Med 2001; 51: 93-9.

Brooks SK, Dunn R, Amlôt R, Greenberg N, Rubin GJ. Training and post-disaster interventions for the psychological impacts on disaster-exposed employees: a systematic review. J Ment Health 2018; DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/09638237.2018.1437610.

Smith CD, Balatbat C, Corbridge S, et al. Implementing optimal team-based care to reduce clinician burnout. National Academy of Medicine (September 2018). Available from URL: https://nam.edu/implementing-optimal-team-based-care-to-reduce-clinician-burnout/ (accessed June 2020).

Embriaco N, Azoulay E, Barrau K, et al. High level of burnout in intensivists: prevalence and associated factors. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2007; 175: 686-92.

Verdon M, Merlani P, Perneger T, Ricou B. Burnout in a surgical ICU team. Intensive Care Med 2007; 34: 152-6.

Welp A, Manser T. Integrating teamwork, clinician occupational well-being and patient safety – development of a conceptual framework based on a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res 2016; DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-016-1535-y.

Willard-Grace R, Hessler D, Rogers E, Dube K, Bodenheimer T, Grumbach K. Team structure and culture are associated with lower burnout in primary care. J Am Board Fam Med 2014; 27: 229-38.

Lin Y, Huang Y. Team climate, emotional labor and burnout of physicians: a multilevel model. Taiwan J Public Health 2014; 33: 271-89.

Mijakoski D, Bislimovska J, Milosevic M, Mustajbegovic J, Stoleski S, Minov J. Differences in burnout, work demands and team work between Croatian and Macedonian hospital nurses. Cogn Brain Behav 2015; 19: 179-200.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge all our ICU team members for their participation in and support of this project. We would also like to express gratitude to the QEII Foundation’s Translating Research into Care Healthcare Improvement Research Funding Program for their support. Together we will build a healthier, stronger workplace.

Author contributions

Jennifer Hancock, Tobias Witter, Scott Comber, and Olga Kits contributed to all aspects of this manuscript, including study conception and design; acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data; and drafting the article. Patricia Daley, Kim Thompson, Stewart Candow, Gisele Follett, Walter Somers, Corry Collins, and Janet White contributed to the analysis and interpretation of data.

Disclosures

None.

Funding statement

This work was supported by the QEII Foundation’s Translating Research into Care Healthcare Improvement Research Funding Program (Grant #: 893267, funding year 2018).

Editorial responsibility

This submission was handled by Dr. Sangeeta Mehta, Associate Editor, Canadian Journal of Anesthesia.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Hancock, J., Witter, T., Comber, S. et al. Understanding burnout and moral distress to build resilience: a qualitative study of an interprofessional intensive care unit team. Can J Anesth/J Can Anesth 67, 1541–1548 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-020-01789-z

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-020-01789-z