By Dave Nelson and Keith Passwater

The Quadruple Aim in health care is a recent adaptation of an earlier concept: the triple aim. The triple aim was first described in 2008 and recognizes that improving the United States health care system requires simultaneous advancement in three dimensions: improving the experience of care, improving the health of populations, and reducing per capita costs of health care.[1] More recently, provider well-being has been added to form the fourth point in what some commentators see as the now quadruple aim.[2]

This article is concerned with techniques and strategies aimed at the per capita cost dimension but not at the exclusion of the other dimensions. Our target audiences are actuaries, finance leaders, and administrators who work with employers, payers, Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs), health systems, and at-risk provider entities. These entities operate in multiple markets under a wide variety of financial circumstances; consequently, it is impossible to offer a cookbook that works in every circumstance. We have, however, tried to offer some general approaches that we believe work in a variety of such situations.

Approaches

In terms of lowering per capita cost, we will focus on six broad approaches to the challenge. Note that these are not mutually exclusive activities as some tend to overlap with one another:

- Addressing outlier costs

- Leveraging the electronic medical record (EMR)

- Implementing change through formal quality improvement efforts

- Applying payer-sponsored health care interventions

- Channeling as much care as possible inside the contracted network

- Adopting physician-driven value-based care

Health risk takers of all types (ACOs, government health care sponsors, employers, and private insurers) are each experimenting with these approaches. This article will describe generally how these approaches work and rank their effectiveness based on the following criteria:

- Ability to prove and sustain material savings

- Creative and effective use of information

- Positive physician and patient engagement

- Feasibility in a particular geography

In the following sections, we share lessons learned about the means of addressing the high cost of health care. These lessons come from our own experience and discussions with physicians and other actuaries.

Addressing Outlier Costs

An outlier in health care often refers to specific patient data exhibiting unusual cost and/or outcomes. However, for this purpose, we define an outlier as a physician whose patients generally consume greater health care resources when compared to other physicians. Of course. there are many causes for differences in patient cost. Merely analyzing volumes of services rendered by physician fails to recognize three major aspects of health care:

- Morbidity: Patients have varying needs based upon their presenting morbidity. Those who are sicker when they visit the doctor will logically require more care than those who are healthier. Analyses that only compare physicians based upon patterns of services neglects this critical reality.

- Multi-diagnosis: Health cost services are delivered in the context of treatment for one or more conditions that require several services, medications, and possibly devices to address fully. Analyses focused only on specific services can be grossly inadequate in comparing physician performance in caring for patients who need an array of services for any particular condition.

- Episodes: The cost of an episode is comprised of many elements. In most cases the controlling physician’s charges are usually modest in comparison to the more significant cost of tests, drugs, work done by other physicians, or facility costs.

Therefore, useful analysis typically tracks risk-adjusted episodes of care compared to each physician’s past practice, the experience of their colleagues, and best practice.

Additionally, it is difficult to build a relevant database, install appropriate software, and hire people who can build reports that are relevant for physicians and fair across physicians. Time, patience, and resources are all needed to identify and address outlier costs.

Ultimately, the goal of an outlier approach is to influence physicians who practice in less efficient ways to adjust practice. Sometimes this involves providing physicians with pertinent information and incenting them to change their practice. Other times it involves changing a corporate policy or incenting physicians to change their referral patterns.

As may be expected, physician reaction to outlier analysis varies. In some cases, outlier physicians challenge the findings based on sample size, inadequate risk adjustment, work done by other providers, patient noncompliance, and the implication that they are doing a bad job. In other cases (such as when physician groups are at risk and looking for ways to improve), outlier physicians are quite interested in reviewing and making changes in response to outlier data.

A fundamental principle of all clinical programs is that physician communication and buy-in are absolutely essential. Of course, physician leaders are the sole credible professionals regarding the determination of appropriate care. Also, physician leaders, working with data analysis professionals, can contribute greatly to the design of effective and fair analyses. The program must gain credibility with practicing physicians or it is of little effect or use.

Physician leaders, once convinced of the program value, can then explain the program—its benefits and its financial incentives—to other physicians. Reports must be easy to review and use, as long, detailed reports are too time-consuming for physicians to accept. One payer shared with us that they try to require just one to two mouse clicks for a physician to reach actionable information. Finally, there needs to be regular discussion with each physician—first to review past performance and later to track performance through the incentive year.

There are many challenges inherent in an outlier approach:

- Leverage: By definition, the approach deals with a small portion of cases (the outliers), as opposed to high-volume episodes where a small change can result in bigger savings

- Alignment: Often physicians are employed by hospitals; consequently, they are often reluctant to refer to lower cost settings

- Compensation: When physicians are paid per service rendered, they are less apt to be interested in the results of an outlier analysis

While outlier approaches must overcome challenges, our research has led us to find some impressive successes. For example:

- An at-risk provider successfully limited inpatient rehab after finding it to be not just expensive but ineffective.

- An insurer counseled an outlier physician to change their method of diagnosing low back pain, which resulted in the physician reducing MRI use from 50% to 15%.

- An insurer shared outlier information with a group of physicians, and they reduced the unnecessary use of the high-cost drug Januvia to treat diabetes.

Leveraging the EMR

At its launch, the EMR (or electronic health record, computer-based patient record) promised to eliminate paper files and clipboards;[3] a 2017 report estimated that almost 86% of office-based physicians are using an EMR.[4] However, today the EMR has become more than a paper saver; it has become a fundamental vehicle for passing physician orders through health systems, monitoring quality, and effecting financial reimbursement, among other functions. Today most physicians use the EMR during patient interactions in order to review history, evaluate recent diagnostic information and determine care plans. Practically then, the EMR is an extremely valuable tool to support physicians with the information on state-of-the-art care for the patient during the patient interaction.

And, despite some concerns,[5] the EMR is an enabler of other cost-savings approaches because implementing best-practice recommendations can be accomplished by placing that recommendation directly into the EMR. In contrast, care alerts delivered to physicians after the fact (often by cell phone text, email, or month-end report) are woefully ineffective. The EMR approach gives physicians just-in-time information that can improve the patient experience. In addition, it generates records that can be studied to improve future care.

Although physician reaction is mixed, adoption of EMRs is changing the role of a physician. Since implementation of the EMR and expanding application, we have observed that many physicians find they are meeting regularly with their colleagues to agree on new preventive guidelines. After agreement at the practice level, physicians are responsible to follow the guideline or enter a note in the EMR explaining why the action was unreasonable (e.g., no vaccine on account of the patient’s allergy to egg proteins).

While views vary greatly (discussed below), it is generally agreed that EMR systems have generated substantial health care and cost management improvements over time. Physicians now regularly get reminders while with the patient on the topics such as the following:

- Recommended Care

- Vaccinations due

- Retinal and foot examinations for diabetics

- Age-appropriate mammograms and colonoscopy screening

- Depression screening

- Special care on account of increased risk of a fall

- Social, Personal, and Family History

- Smoking status

- Domestic violence

- Status of advance directive

- Medication compliance

EMR systems significantly reduce the likelihood that gaps in care (or errors) will occur. This is especially true with medications where EMR systems reduce or eliminate the misread of an order, misfiling of an order, orders not being filled, or adverse drug interactions. EMR systems also make it more difficult for physicians to order a nonstandard dose of a medicine that could be an error. And by reducing errors (though not eliminating all), effective use of an EMR should improve medical outcomes and reduce costs.

Additionally, benchmark data, available through EMR systems, can be used to encourage physician attention to evidence-based best practices. In this regard, the EMR system supplies relevant information (by patient, by facility, by system, across the world, and by physician) so the physician can see how they are doing this year compared to last year, even if there is no financial incentive associated with the review. Most physicians, like humans in general, believe they are better than average (the Superiority Illusion)[6] and they have a natural desire to stay current or ahead of their peers. If such physicians see data that is inconsistent with their positive view of themselves, most will try to improve—particularly if the data is credible (see earlier comments about physician leader involvement).

EMR data can also impact the care of specific patients. Prior to treatment for a condition with multiple appropriate treatments, physicians can see how different treatments affected similar patients across the EMR provider’s total patient population.

Physicians with reservations about the advent of EMR systems express several concerns. For some, EMR systems are “taking the fun out of medicine.” Effective use of an EMR is reported by physicians to require 1 minute outside patient interaction for every 2 minutes spent with the patient. Worth noting, these same physicians report spending an additional half the time with patients in the EMR.[7] In addition, poorly designed EMR systems—that in some cases produce multipage standard reports just to say that everything is “OK”—are inherently very difficult for physicians to use.

Also, some have observed that there appears to be a generational divide on physician opinions of EMRs.[8] Older physicians often complain about “cookbook medicine” and begrudge the extra time it takes to complete EMR forms. Meanwhile, younger physicians, having grown up with EMR systems, are more likely to perceive benefits of an EMR system that justify the time demand.

In support of those physicians’ concerns about the time demand, several things can be done to make EMR systems easier to use. Examples include the following:

- Delegation by the physician can ease the burden and allow them to focus on more complex care

- The nursing care team can follow up on preventive measures

- Onsite assistants can transcribe physician notes (although this is becoming a less frequent solution due to cost and the disconnect to EMR real-time care prompts)

- Interface improvement aimed at efficiency

- Voice recognition software can speed data entry

- EMR care prompts can relieve the physician of separate research in some cases

Another concern about EMRs involves data sharing (interoperability) in markets where multiple EMR vendors operate. In such markets, organizations like Patient Pings use EMR records to deliver real-time notifications whenever patients experience care events—whether they show up at a hospital, emergency room, or other post-acute facility.

Finally, a small but growing complication is the legal requirement that patients may be permitted to limit the use of their data to their exclusive treatment. Patients who make this choice effectively withdraw from studies of clinical effectiveness. Currently relatively few patients have made such a designation, but in the future, this might cause greater limitations to population studies.

Formal Quality Improvement Efforts

Quality improvement often involves a structured approach to evaluating the performance of systems/processes and determining needed improvements in both functional and operational areas. Successful efforts we’re aware of rely on the routine collection and analysis of data. Many areas that have used this approach have experienced significant gains. For example:

- Farming costs have been decreased $15-20 per acre (while maintaining or increasing crop yields) through systematic soil sampling and GPS systems allowing different fertilizer combinations to be applied every few feet.[9]

- Data analytics have dramatically reduced waste and cost (increased quality) across many types of companies.[10]

- Consumer knowledge of home prices is increasing and the percentage fee paid to real estate brokers is falling with the advent of online home sale tools.[11]

So, it is widely assumed and intuitive that the refinement of processes might generate similar transformations in health care. Unfortunately, until recently medicine has not seen the same gains as other areas of the economy.

But over the past 20 years, medicine has started to make strides. For example:

- Highmark has built care models in 10+ practice areas (e.g. CHF, COPD, joint, palliative care). By using a structured approach—covering virtually all of the concepts discussed in this article—they have improved care and lowered cost. As might be expected, the furthest-along program—stroke care—has been blessed with highly engaged physician leadership.

- At the 2019 Society of Actuaries (SOA) Health meeting, Michael Goran, MD, reported that improvements in knee surgery resulted in more home care, less facility care, and reduced post-surgery infections.

- BCBS Michigan funded the Michigan Bariatric Surgery Collaborative (MBSC), which improved bariatric care and resulted in 64 scholarly articles (see michiganbsc.org).

- In 2000, one Madison, Wisconsin, hospital joined a nationwide effort to reduce infections. A 10-point checklist was created for patient care. Initially the checklist was a paper document. Today those 10 points are part of the EMR system. Significant events dropped a staggering 98%.

Hospital-based quality improvement work has become a big deal, and hospital accreditation has become tied to having an effective Quality and Safety Committee. In most hospitals, those Quality and Safety Committees are making sure that the following work is being done (often, through the use of the EMR):

- Drug-drug interactions or inappropriate drug dosing is immediately identified

- Allergies are identified and clearly noted and marked in multiple locations

- All care is properly recorded by time, prescriber, caregiver, etc.

- Adverse events and poor outcomes are noted and reviewed

The beauty of quality improvement work is that efforts to improve care and reduce variation routinely eliminate waste and reduce cost. The work is anything but easy, though. Unless there is strong physician and hospital leadership and aligned financial interests, data won’t be gathered consistently, standard approaches won’t be agreed to, and a lot of meetings will take place with little impact. Often the process to be studied involves separate hospitals, clinics, labs, and physician practices, many of which have different owners and different financial concerns. Establishing initial goals and dedicated funding before the quality improvement effort is started can be a project in and of itself.

Payer-Sponsored Health Care Interventions

In 2008, Ian Duncan chronicled in his book Managing and Evaluating Healthcare Intervention Programs analysis of preauthorization, concurrent review, case management, demand management, disease management (DM), specialty case management, population health management, the medical home, and wellness.

Duncan found that financial improvements have been hard to measure on account of issues including publication bias, regression to the mean, the same patients being targeted for multiple disease management programs, patient selection bias, patient dropouts, claims run out, outliers, difficulties enrolling patients, and risk differences. In his book, Duncan cited a Congressional Budget Office study, which found that “there is insufficient evidence to conclude that disease management programs can generally reduce the overall cost of health care.”

While it certainly does appear true that DM programs show limited to no success, it’s possible that a contributing factor is impacted health care workers, physicians, and patients often see DM and other health care interventions as just another hassle as opposed to a potential health outcome improvement. Clinicians and administrators, who are paid by payers to perform such interventions, are frequently seen as a nuisance. As a result, the interventions may be doomed to fail before they begin.

Worth noting, many of these health care intervention programs skipped the important first step: create understanding, financial incentives, and buy-in among physicians (and patients) about the aim of the intervention to improve care. This frequent lack of buy-in may explain why Duncan has rightly observed that intervention efforts are often not able to contact or enroll a large share of targeted patients. And, a lack of full commitment among those who are enrolled in an intervention may explain why those patients don’t experience material difference in their health outcomes compared to those who do not receive the intervention.

As a result of the inconclusive evidence for intervention effectiveness, venture capital companies have struggled to get payers to sign up for new health care interventions. Payers have grown skeptical of such initiatives in the absence of data verifying the savings of past efforts, even for venture capital firms willing to put a significant portion of fees at risk depending upon actual savings for the payer. In addition, multistate payers have had had difficulty transferring those programs that do work well in one market to other markets where provider dynamics are different.

At the end of Duncan’s book, he predicted:

- More wellness for the masses through the internet

- Fewer, more targeted interventions aimed at the highest-cost cases

With time, we believe both of these predictions will seem accurate. The world is now full of phone applications and wellness devices that track our steps, our heart rate, our sleeping pattern, the weight recorded on our scale, and our glucose levels. There are also new mobile apps that monitor conditions like blood pressure compliance (apps can tell if the bottle is opened every day or keep track of self-reported data about the taking of pills). Many times, these devices are purchased by consumers based on the presumption of their effectiveness rather than randomized controlled studies.

Another targeted intervention area that has shown growth is in promoting hospice care (both in an institution and in the home). Almost all the physicians with whom we talked expressed the view that care in the final stages of life—with an incurable condition—is far too costly. These same physicians also expressed the opinion that non-value-added care in the last year of life is more than an issue for medicine: It’s a societal issue in the United States. Families often feel their loved ones need the expensive treatment without regard to cost or effectiveness (“our insurance pays for the brand …. my relative should not be treated with a generic”). It may also be true that physicians shy away from end-of-life discussions because they have not been trained to initiate these types of conversations.

Recently, though, vendors have emerged to deliver caring, credible advice to families mourning the pending end of life for a loved one. And many families are choosing to live those final days in the comfort that can be provided without chasing hoped-for miraculous treatments that render the patient loved one unable to enjoy their remaining days. Patients and families often report greater satisfaction with such care.[12]

Another targeted intervention space regards patients with multiple chronic conditions. These patients receive a review of their drug list to avoid overmedication and minimize negative drug-drug interactions (an all-too-common problem with these patients[13]), information about hospice, regular home visits, and a host of other services. One challenge of these programs is that involved parties (health care providers, enabling vendors, and payers) disagree about how to apportion any realized savings, which stymies implementation.

Channeling Care In-Network

Turning our attention to health care systems, it is important that the providers performing services are allowed to operate at optimal capacity. Not only are underutilized health care providers costly to maintain (i.e., fixed costs frequently account for 50%+ of total costs), but a significant volume of patient experience is needed for providers to improve outcomes. Consequently, some of the highest-payback, lowest-pushback improvement efforts involve efforts to keep care in-network. Typically, these efforts focus on the following:

- Development of easy-to-use information—either through analysis of internal referral patterns and service data, or comparison to market data—to identify what care is being delivered outside the system, or

- Development of narrow networks where physicians and facilities are carefully selected for their quality, cost profiles, and willingness to refer care to targeted facilities.

Capacity planning is not just a matter of keeping facilities full. The coronavirus pandemic of 2020 has taught us that excess capacity and flexibility are needed to address a massive spike in patient demand for some services while demand for other services falls. The pandemic has driven innovation in how we flex existing structures for temporary inpatient use. Examples seen during the pandemic include previously shuttered hospitals, convention centers, and a former daily newspaper headquarters.[14] As coronavirus demand is expected to wane within 12 to 24 months, it is very unlikely that permanent hospital facilities will be built to support long-term spikes in demand. Rather, it’s much more likely that the explosion in telemedicine will continue to some extent and we will implement better planning for facility contingencies going forward.

Physician-Driven Value-Based Care

Both private insurers and government agencies have taken numerous steps to share financial risk with providers. Publicly traded insurers frequently tout to investors the number of at-risk provider contracts in place. Congress continues to roll out programs like the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act (MACRA), which rewards health care providers for giving better care, not more service.

It is widely agreed that when physicians are incented to lower costs, all of the other programs described in this article tend to be more successfully implemented. This is particularly true for implementing payer-sponsored health care interventions and lowering outlier costs, which can shift from provider nuisances to a necessity in an environment where physicians are incented and engaged.

That said, it has been difficult to move away from fee-for-service medicine. Our own experience has shown that some patients will pay extra out of pocket to avoid plan provisions intended to steer them to more efficient providers. Employers, eager to retain top talent, have offered plans that allow their employees to get care anywhere they choose. Hospitals have purchased physician practices to steer care toward owned facilities. So, while physician-driven value-based care is desirable, it is not always possible or relevant.

There is some evidence that care has been withheld in some instances,[15] but the authors of this article speculate that recent changes by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) to promote quality (i.e., under the Stars program, all contracts earning 4 or 5 Stars receive additional Medicare revenue) have influenced clinical practice so that at-risk physicians are now more likely to deliver preventive medicine.

Evaluation of Different Approaches

In the right circumstance, all the approaches we have discussed above can be very effective. There are, however, usually several conditions (listed below) that must be present for any care efficiency approach to succeed. It is also true that failure to ensure any of the following conditions are present can serve as a fatal flaw.

- Physician engagement is always crucial. As mentioned previously, programs with physician input, buy-in, and leadership will generate better quality and often lower costs—whereas programs without physician input, buy-in, and leadership are likely to fail.

- Patient engagement is also very important. If members perceive a program to restrict their care, the program will eventually fail in most circumstances. It should be noted, however, that in most cases the patient will be supportive if his/her physician endorses the program-driven course of treatment.

- Actionable, easy-to-use data is critical to effective improvement efforts. As mentioned earlier, voluminous reports are ineffective. Additionally, extraneous information may appear value-added to data scientists, but concise, on-point analytics are vital to enabling clinicians to take interventions consistent with the program intent. Extra value can be generated here when an effort generates valuable information that can be used by other improvement efforts without distracting from indicators needed for the primary program.

- Proof of concept and sustained material savings are important to secure appropriate funding. In many instances initial funding for new health care ideas can come from government, health systems, or payers based on the perception of value. But frequently venture capital/private equity (VC/PE) firms are the source for funding new ideas. VC/PE firms, of course, must move an idea into the revenue-generation phase as quickly as possible. And winning payer and provider customers requires proof of concept (savings).

- Geographic applicability is always key. Not all interventions work in all markets. For instance, some processes require linkages between primary care, specialists, and health care facilities that are not always present. Some markets have existing partnership structures that make a concept work well, while other geographies have too much fragmentation to be effective. Additional considerations include the political dynamics, payer market shares, and funding source requirements.

Bringing It All Together

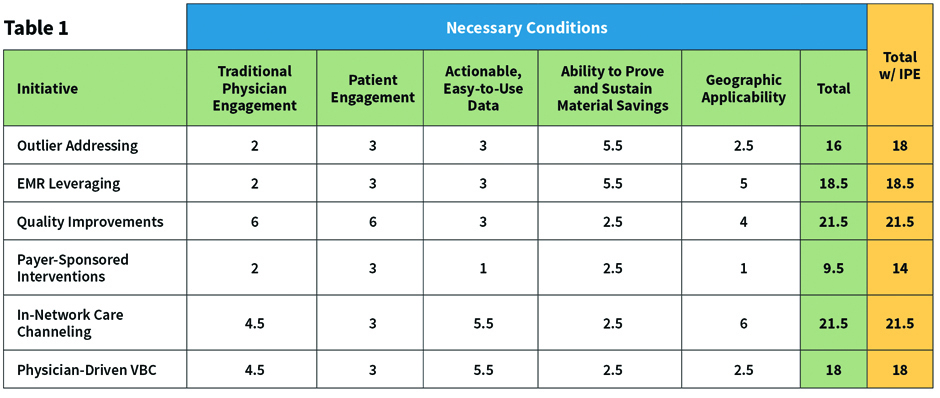

As a way to judge what we believe to be the relative difficulty of pursuing different approaches, we ranked each of the six approaches on the conditions in Table 1. A value of 1 represents the approach most difficult to achieve and 6 represents the easiest to achieve. In some cases, we perceived ties, which we recorded as an average of multiple approaches.

We also hasten to acknowledge that none of these approaches are easy. Additionally, rankings like these are fraught with oversimplification and present ubiquitous invitations to present contradictory examples. We readily accept that in order to perform this analysis effectively, many more conditions and risk factors should be evaluated by actuaries and other experts in health care cost analysis. But, for the sake of article brevity, these are our simple rankings.

The reader will notice the far-right column in Table 1 titled “Total w/IPE,” which is the total adjusted for Intentional Physician Engagement. The values in this column represent the relative strength of the initiative if physicians are fully engaged from the outset. The practical impact, as we see it, is in the Outlier and Payer-Sponsored Interventions where programs are sometimes implemented without thorough physician engagement. As we have asserted previously, limited physician engagement compromises program effectiveness.

Despite the acknowledged weaknesses, we believe the simple analysis in Table 1 provides a helpful initial basis to evaluate health care cost improvement efforts. Our analysis suggests that keeping care in-network has the highest likelihood of achieving cost efficiency. However, the best initiatives often incorporate multiple cost control levers. Health risk-takers would be wise to review initiatives based on their intent and ability to impact multiple levers simultaneously. Decision-makers should also remember—physician engagement is critical.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Conrad Andringa, MD; William Cashion, MAAA, ASA; Ian Duncan, MAAA, FSA; Ewa Matuszewski, CEO and co-founder, MedNetOne Health Solutions; Geoff Priest, MD; Mark Wernicke, MAAA, FSA; and Doug Woll, MD for sharing their perspectives concerning cost-improvement opportunities and challenges.

Dave Nelson, MAAA, FSA, is senior adviser at PascoAdvisers.

KEITH PASSWATER, MAAA, FCA, FSA, is managing director of PascoAdvisers and a senior adviser with Oliver Wyman.

Endnotes

[1] Berwick, Donald & Nolan, Thomas & Whittington, John. (2008). The Triple Aim: Care, Health, and Cost. Health affairs (Project Hope). 27. 759-69. 10.1377/hlthaff.27.3.759. Note: recently people have started to discuss the need for a quadruple aim which considers an improved clinical experience to offset the trend where decreased staff engagement, or burnout, lowers patient satisfaction, negatively impacts health outcomes, and increases cost.

[2] T. Bodenheimer & C. Sinsky. From Triple to Quadruple Aim. Annals of Family Medicine. Nov 2014. pp. 573-576. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4226781.(accessed May 5, 2020)

[3] R. Dick, E. Steen, D. Detmer DE, editors (Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Improving the Patient Record). The Computer-Based Patient Record: Revised Edition: An Essential Technology for Health Care. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 1997.

[4] K. Myrick, D. Ogburn, B. Ward. Table. Percentage of office-based physicians using any electronic health record (EHR)/electronic medical record (EMR) system and physicians that have a certified EHR/EMR system, by U.S. state: National Electronic Health Records Survey, 2017. National Center for Health Statistics. January 2019.

[5] F. Schulte, E. Fry. Death By 1,000 Clicks: Where Electronic Health Records Went Wrong. Kaiser Health News and Fortune Magazine. March 18, 2019.

[6] M. Yamada, et. al. Superiority illusion arises from resting-state brain networks modulated by dopamine. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States. March 12, 2013. www.pnas.org/content/110/11/4363 (accessed April 1, 2020)

[7] Stanford Medicine & Harris Insights & Analytics. How Doctors Feel About Electronic Health Records. March 2018. med.stanford.edu/content/dam/sm/ehr/documents/EHR-Poll-Presentation.pdf. (accessed May 27, 2020)

[8] S. Decker, E. Jamoom, J Sisk. Physicians In Nonprimary Care And Small Practices And Those Age 55 And Older Lag In Adopting Electronic Health Record Systems. Health Affairs. May 2012. doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2011.1121 (accessed May 27, 2020)

[9] T Maddox. Agriculture 4.0: How digital farming is revolutionizing the future of food. TechRepublic. December 12, 2018. www.techrepublic.com/article/agriculture-4-0-how-digital-farming-is-revolutionizing-the-future-of-food/ (accessed May 27, 2020)

[10] V. Dilda, et. al. Manufacturing: Analytics unleashes productivity and profitability. August 14, 2020. McKinsey & Company. www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/operations/our-insights/manufacturing-analytics-unleashes-productivity-and-profitability (accessed May 27, 2020)

[11] Competition in the Real Estate Brokerage Industry. A Report by the Federal Trade Commission and U.S. Department of Justice. April 2007. www.justice.gov/atr/competition-real-estate-brokerage-industry#IIB (accessed May 27, 2020)

[12] B Frist. A New Model of Community Care: Aspire Health And Transforming Advanced Illness Care. Forbes. May 30, 2017. www.forbes.com/sites/billfrist/2017/05/30/a-new-model-of-community-care-aspire-health-and-transforming-advanced-illness-care/#757c36f3b76a (accessed May 27, 2020)

[13] B. Kannan, et. al. Incidence of Potential Drug-Drug Interactions in a Limited and Stereotyped Prescription Setting – Comparison of Two Free Online Pharmacopoeias. Cureus. Nov 22, 2016. doi: 10.7759/cureus.886 (accessed May 27, 2020)

[14] J. Rose. U.S. Field Hospitals Stand Down, Most Without Treating Any COVID-19 Patients. NPR. www.npr.org/2020/05/07/851712311/u-s-field-hospitals-stand-down-most-without-treating-any-covid-19-patients. (accessed May 27, 2020)

[15] JD Reschovsky, et. al. Effects of compensation methods and physician group structure on physicians’ perceived incentives to alter services to patients. Health Serv Res. 2006;41(4 Pt 1):1200-20. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00531.x