As federal troops and militarized police descended on protesters, John Lewis pleaded for nonviolence. Cynthia Tucker shares her hope that a new generation of activists can learn from his courageous and peaceful fight for “beloved community.”

By Cynthia Tucker

President Donald J. Trump is conducting his second presidential campaign the same way he conducted his first — as the heir to George Wallace. Trump hasn’t stood in the schoolhouse door, but he has defended Confederate monuments, encouraged police brutality with a phrase Wallace adopted — “when the looting starts, the shooting starts” — and threatened to unleash “vicious dogs” on protestors. Wallace’s rage, resentment and racism are all explicit in Trump’s rhetoric.

Congressman John Lewis (D-Ga.) knows the playbook all too well. In January 2016, as Trump was mowing down what remained of the Republican establishment, Lewis brought his own history to an analysis of Trump.

"I've been around a while and Trump reminds me so much of a lot of the things that George Wallace said and did. I think demagogues are pretty dangerous, really... We shouldn't divide people, we shouldn't separate people," he told the Los Angeles Times.

It’s at once remarkable and tragic that Lewis’ legacy — his lifetime of patient, optimistic and non-violent resistance to systemic racism — remains so relevant. He has given 60 years to the work of trying to build the “beloved community” only to arrive at a moment when that work may seem naive, that community farfetched, the dream a child’s fantasy.

Just consider the recent fate of peaceful protestors gathered in Lafayette Square, across from the White House. It was reminiscent of earlier, even uglier scenes — now-historic images of law enforcement authorities viciously attacking civil rights demonstrators during the 1960s. While police and National Guard troops didn’t unleash dogs or fire hoses on June 1, they did lob tear gas, pepper balls and flash-bang grenades into the crowd, advancing on unarmed men and women with riot shields and batons. Though White House officials lied about the weapons and tactics used, video showed police using a devastating chemical meant to blind, choke and burn, a tear gas the manufacturer admits can kill. Protestors were left dazed, bleeding, stunned.

Viral video clips from across the country have shown police officers responding to the demand that they end their brutality by upping the ante — rolling down city streets in armored personnel carriers, arresting journalists or injuring them with rubber bullets, beating unarmed demonstrators. In one clip, Buffalo police officers were seen knocking down a 75-year-old protestor and walking past him as he bled from his head.

But Lewis’ faith in the persuasive appeal of non-violent protest is undimmed, no matter the viciousness of law enforcement agents on the other side. As largely-peaceful demonstrations were accompanied by sporadic episodes of destruction, Lewis insisted that his lifetime of advocacy points to a more powerful weapon.

“I truly believe that, in keeping with the teachings of Gandhi, of Martin Luther King, of Jesus, that we cannot give up on the way of non-violence, the way of peace, the way of love,” he told me. “If we are going to create the beloved community, if we are going to redeem the country, redeem the world, we have to do it by respecting the rights of all human beings.”

He posted a similar message on his U.S. House of Representatives website: “To the rioters here in Atlanta and across the country: I see you, and I hear you. I know your pain, your rage, your sense of despair and hopelessness. Justice has, indeed, been denied for far too long. Rioting, looting, and burning is not the way. Organize. Demonstrate. Sit-in. Stand-up. Vote. Be constructive, not destructive. History has proven time and again that non-violent, peaceful protest is the way to achieve the justice and equality that we all deserve.”

Lewis’ words drew broad support, but they also, predictably, elicited criticism from some who believe that non-violent protest is musty, fusty, old-fashioned, futile. According to The Atlanta Journal-Constitution, a tweet from a user with the moniker @SmizeEyes snarled: “Look how well that approach turned out for Martin Luther King Jr. & you. I’m sure you still feel the mental & physical scars from that.”

Well, yes. Not only was King murdered for pursuing equality under the law, but so were many others — some well-remembered but many all-but-forgotten. And countless men and women, people like Lewis, put their bodies on the line only to have them stomped, smashed and broken by racist authorities and their savage civilian supporters.

Despite the bigotry and brutality he endured, despite the continued failings of American democracy, despite the backlash that followed the election of the nation’s first black president, Lewis has maintained his optimism. And, as he said to me, “I’m still here,” (despite a diagnosis of stage four pancreatic cancer) “fighting the good fight.”

He remains a faithful adherent of a belief that Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. popularized through a quote adapted from a sermon by 19thcentury abolitionist preacher Theodore Parker: “The moral arc of the universe is long, but it bends toward justice,” King said.

In the time of Trump, though, Lewis’ optimism can seem out of place, the patience it preaches ill-suited to the challenges of resurgent racial bigotry, white nationalist terrorism and unrestrained xenophobia. Some progressives have complained that a belief in that long moral arc may breed apathy.

“The use of the quotation. . .carries the risk of magical thinking,” warned writer Mychel Denzel Smith in a 2018 piece in HuffPost. “After all, if the arc of the moral universe will inevitably bend toward justice, then there is no reason for us to work toward that justice, as it’s preordained.”

But that is hardly Lewis’ view. His entire life has been a struggle for that justice, a quest for a more perfect union, a campaign for the full equality that America has always championed in its mythology but never practiced in its civics or culture.

And a fuller, deeper look at the decades since he marched as a young man shows the power of nonviolent civil disobedience, the gains he and others gave us, the progress for which they sacrificed. I remember. I am old enough to testify to the changes wrought by the nameless thousands who marched, chanted, sang, prayed, took one knee or two, but never broke a window, set a fire or even raised a fist in retaliation.

In 1960, black motorists taking road trips were frequently denied access to white-owned hotels and restaurants and public toilets, even in the Northeast and Midwest. That’s ancient history for today’s traveling classes, black, white and brown. In 1960, about 43% of whites received high school diplomas while only 23% of black students did. Today, the gap has nearly closed: 83% of black students achieve high school diplomas, while 87% of white students do. In 1960, Black politicians were restricted to local offices in majority-Black communities. Now, there are thousands of Black elected and appointed representatives across the nation, serving as school board officials, mayors, county commissioners, state legislators, judges and members of Congress, where a Black man, Rep. Jim Clyburn (D-S.C.) is House majority whip. There are currently two Black men, Sens. Cory Booker (D-N.J.) and Tim Scott (R-S.C.), and one Black woman, Sen. Kamala Harris (D-Calif.), in the U.S. Senate, often referred to as the world’s most exclusive club.

The sacrifices of civil rights crusaders led not only to opportunities for Black doctors, engineers and astronauts, Black professional-league coaches and managers, Black billionaires and Fortune 500 CEOs but also led to the election of the nation’s first Black president. Lewis, after all, was beaten bloody on Selma’s Edmund Pettus Bridge for having the temerity to demand the ballot for all Black citizens.

Certainly, the rage playing out on streets across the nation is justified. So are the grief, anxiety, sorrow and hopelessness. How many unarmed and defenseless Black men, women and children will be shot, choked or bounced around to the point of death in the back of a police van before the entire nation demands systemic change?

Ironically, some of the simmering rage may have its foundations in the promise of Barack Obama’s presidency, which could never have fulfilled generations of pent-up expectations. Yes, racism is alive and well in America. It was written into its Constitution, woven into Betsy Ross’ flag, a cornerstone of its founding institutions.

Lewis knows that as well as anyone. And his response, as he says in speeches around the country, is to urge his listeners to “get in good trouble” — his description of non-violent protest and other forms of activism for social justice.

“I was so inspired to see the hundreds, the thousands, of people all over the world taking to the streets, especially the young people. They are being heard,” he told me.

Those who discount Lewis’s brand of activism should review his history. He has been accused before of being out of touch, of lacking courage, of being an “Uncle Tom.” His unflagging faith in the power of nonviolence to redeem his nation has not always won him accolades.

I got to know Lewis, both personally and professionally, when he was a member of the Atlanta City Council, a position from which he worked tirelessly to represent his constituents while calling out the backroom deals and shady business alliances of some of his colleagues. Even that made him unpopular in some circles.

His decision to seek a Congressional seat that many Black leaders believed should and would go to Julian Bond — the handsome, sophisticated and witty state legislator who had been a close friend of Lewis as a co-leader of the student movement — made him seem crazy. But Lewis brought to that campaign the same indefatigable spirit, the same physical fortitude and the same unflagging belief in the promise of American democracy he brought to his civil rights crusades. He won the seat in 1986 and has held it since.

He grew up dirt-poor in a rural area of southern Alabama at a time when the murders of Black men and women at the hands of white law enforcement officials were routine and unremarked upon. Any whiff of protest would have been dangerous. But he and his family listened on the radio to news of the Montgomery bus boycott, and he was deeply impressed. He wanted to be like Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

Lewis went to college in Nashville to study for the ministry — scrubbing pots and washing dishes in the school cafeteria to pay his tuition — but he quickly became engaged by the teachings of a young Black minister he met named James Lawson, who was field secretary for an organization called the Fellowship of Reconciliation. Lawson had been sent to jail for his pacifism during the Korean War, and he taught classes in Nashville on nonviolent civil disobedience.

Lewis studied. And studied. He was introduced to the teachings of philosophers from Reinhold Niebuhr to Mohandas Gandhi. The commitment to non-violent activism required not only passion for the cause of social justice but also discipline, the capacity for restraint and a profound understanding that the ultimate sacrifice might be required. That took an uncommon kind of courage. Lewis eventually attended workshops at the well-known Highlander Folk School, where his grasp of the tactics of nonviolent protest was refined. “I left Highlander on fire,” he wrote in his memoir, Walking With the Wind.

In preparation for their crusade of civil disobedience, Lewis, along with several other budding young activists, from Diane Nash to Marion Barry, role-played in order to be ready for the taunts, the threats and the fists of white segregationists. Those study sessions were soon to be tested in Nashville, where Lewis joined others to desegregate lunch counters and movie theaters.

But the real test of those teachings came during the spring and summer of 1961, when he joined other passengers, Black and white, to desegregate interstate buses in a campaign they called “Freedom Rides.” Buses were bombed and burned, and the freedom riders were set upon by vicious mobs of whites armed with clubs and sticks at stops along the way, as law enforcement officials looked on, passively. Violent whites were not arrested, but the freedom riders were. But they kept riding, knowing they could be killed for exercising their rights as citizens.

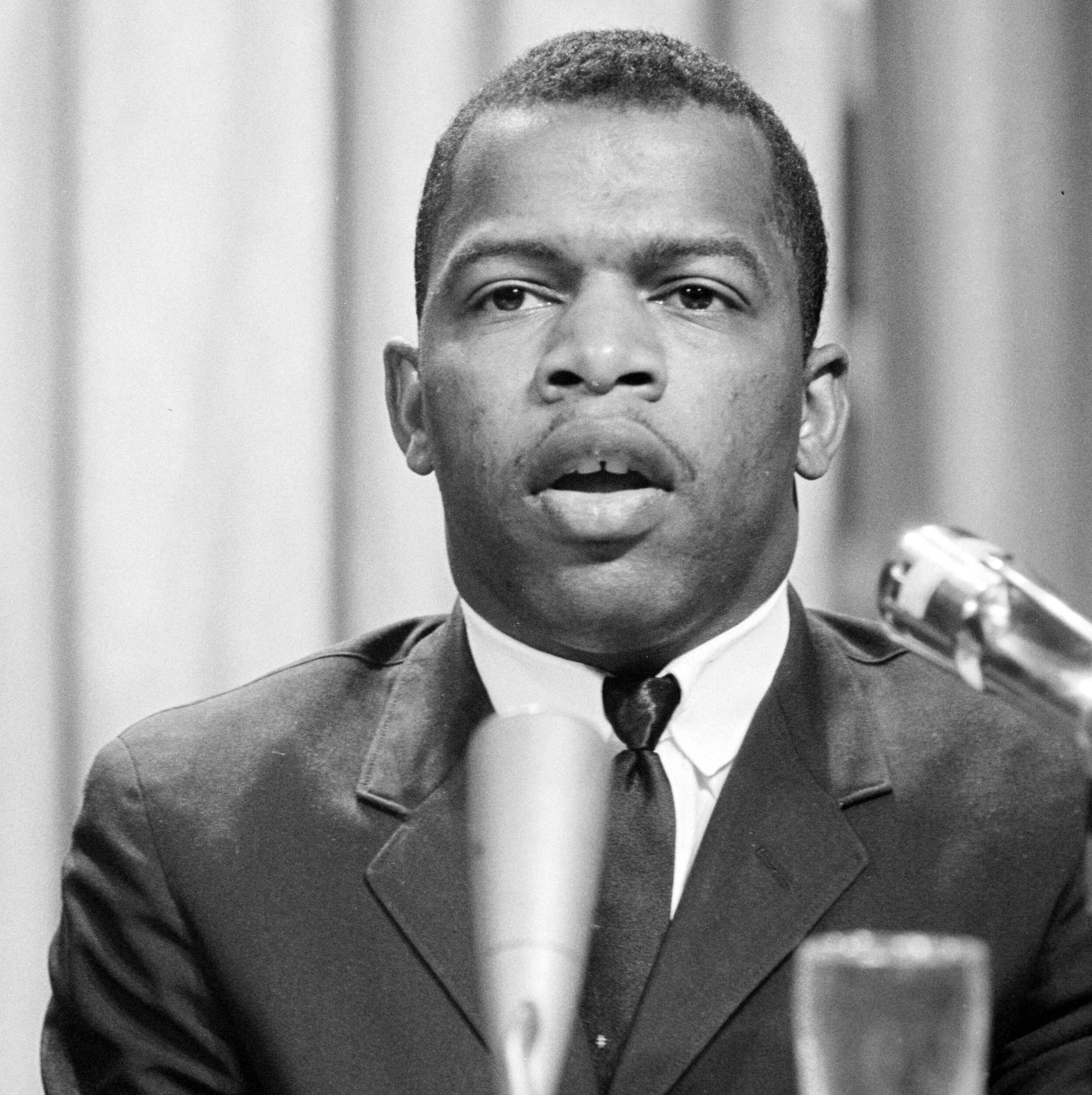

Pictured: John Lewis at meeting of American Society of Newspaper Editors in 1964 (first image). Civil Rights March on Washington, D.C. [Leaders of the march (from left to right) Mathew Ahmann, Executive Director of the National Catholic Conference for Interracial Justice; Cleveland Robinson, Chairman of the Demonstration Committee; Rabbi Joachim Prinz, President of the American Jewish Congress; A. Philip Randolph, organizer of the demonstration, veteran labor leader who helped to found the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, American Federation of Labor (AFL), and a former vice president of the American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations (AFL-CIO); Joseph Rauh, Jr, a Washington, DC attorney and civil rights, peace, and union activist; John Lewis, Chairman, Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee; and Floyd McKissick, National Chairman of the Congress of Racial Equality.]

As the Freedom Rides drew national attention, they gained supporters — and passengers — from all over the country. Lewis was grateful for the attention but worried that some of the participants lacked the training they needed. “Our campaign had grown to include riders who came with all their heart and soul and courage to put their bodies on the line for the cause of racial and human justice, but who were not necessarily familiar with nor committed to the way of non-violence. This caused some tension among us during our stay in Mississippi,” he wrote in his memoir, when some riders were jailed there.

That doesn’t mean Lewis never got angry. In one telling episode, in 1963, the elders in the civil rights movement erupted in frustration and dismay over the text of the speech he was to make at the historic 1963 March on Washington. Chairman of the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) at age 23, Lewis had written a speech that older leaders thought was too fiery, too demanding, too angry. It used the word “revolution.” But he complied with the request to tone down his rhetoric because he thought the moment — and the movement — were bigger than any single individual.

As so many of us were, Lewis was ecstatic when Obama was elected, but he knew better than to believe that it heralded a “post-racial America.” Celebrating the 50th anniversary of the March on Washington in 2013, he said, “If you ask me whether the election of Barack Obama is the fulfillment of Dr. King’s dream, I say, ‘No, it’s just a down payment.’ There’s still too many people 50 years later, there’s still too many people that are being left out and left behind.”

And, so, he kept on working, casting votes in Congress for progressive causes and making speeches around the country encouraging young people to “get in good trouble.” March, his graphic novel trilogy about the civil rights movement, was on The New York Times bestseller list for six consecutive weeks, introducing the power of nonviolent protest to a generation of young folk bored by speeches and history texts. (That trilogy, by the way, would be an excellent resource for the many leaders of the protests who are advocating non-violence and for those who intercede when they see interlopers at the marches fomenting trouble.)

And what about voting as “good trouble”? In an impassioned essay in The New York Times, well-known Democratic activist Stacey Abrams acknowledged, “Voting feels inadequate in our darkest moments.” Yet she urged those sick and tired of being sick and tired to cast a ballot. (She also quoted Lewis in the essay.) “Voting is an act of faith. It is profound. In a democracy, it is the ultimate power,” she wrote.

Lewis, of course, echoes that. “I happen to believe the vote is the most powerful non-violent tool we have in a democratic society,” he told me. “We cannot give up on the democratic process. We have to vote.”

He reiterated the need to vote not only in high-profile presidential elections but also in local elections, where district attorneys and judges are on the ballot. “If it’s only a dog-catcher running, you need to vote. People spilled blood for the right to vote. People gave their lives,” he said.

Asked about the November elections, Lewis said, “I am very hopeful. I am optimistic. We are going to turn America around.”

His undying hope for America lies not in any sense of its imminent perfection but rather in his conviction that the “beloved community” will one day come to fruition only if those who are committed to justice and equality keep on keeping on, one step at a time, no matter how hot the sun, no matter how back-breaking the work, no matter how brutal the forces on the other side. That’s his legacy, and it is a fitting response to these Trump-addled times.

Cynthia Tucker is a Pulitzer-Prize-winning newspaper columnist and journalist-in-residence at the University of South Alabama, where she teaches journalism and political science classes. She came to know John Lewis early in her career, when she was an editorial writer for The Atlanta Journal.

More from The Bitter Southerner