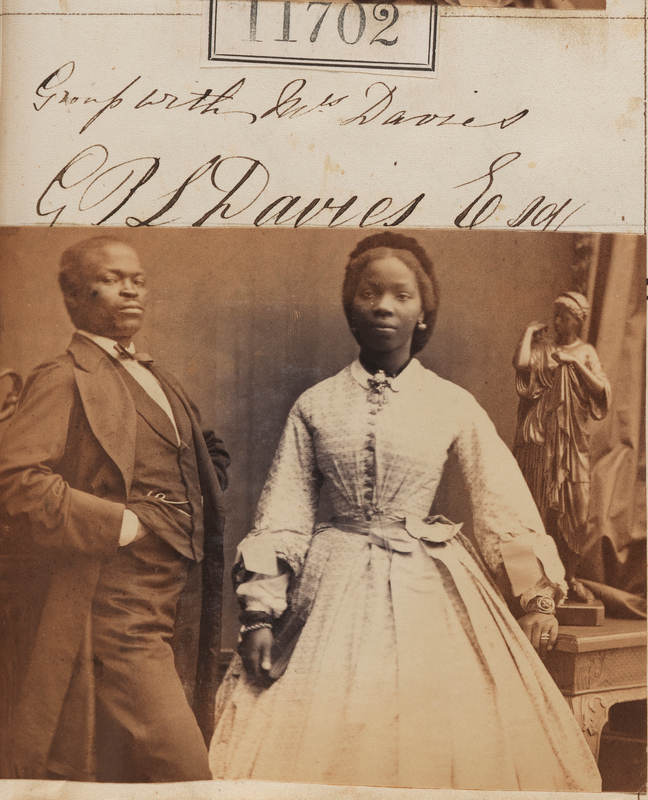

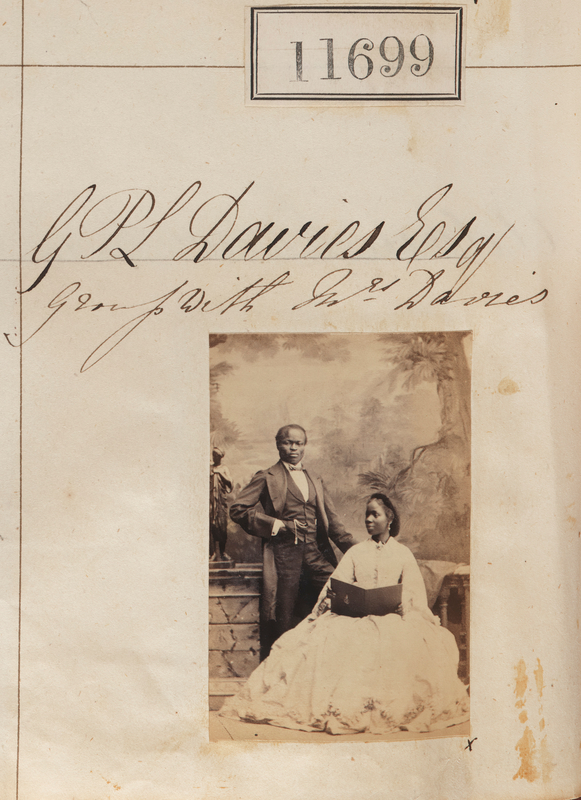

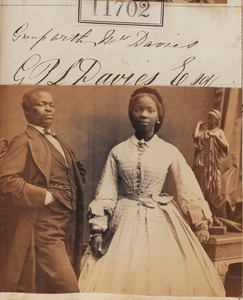

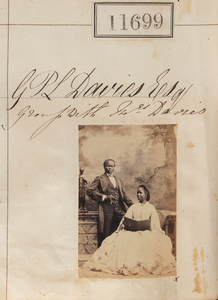

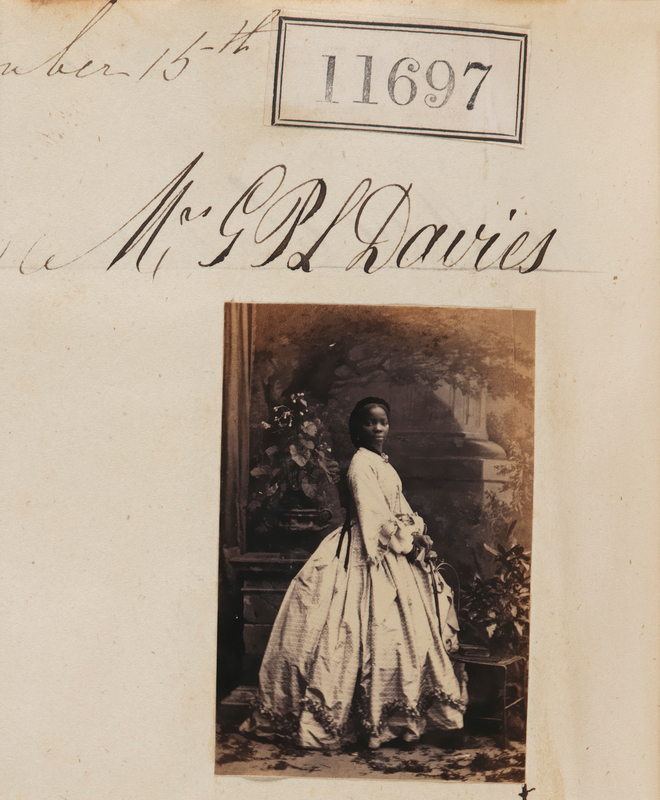

In 1862, the celebrated French photographer Camille Silvy captured the likeness of Sarah Forbes Bonetta (1843–1880) in a series of photographs that are now in the collection of the National Portrait Gallery.

Sarah Forbes Bonetta

1862, photograph by Camille Silvy (1834–1910)

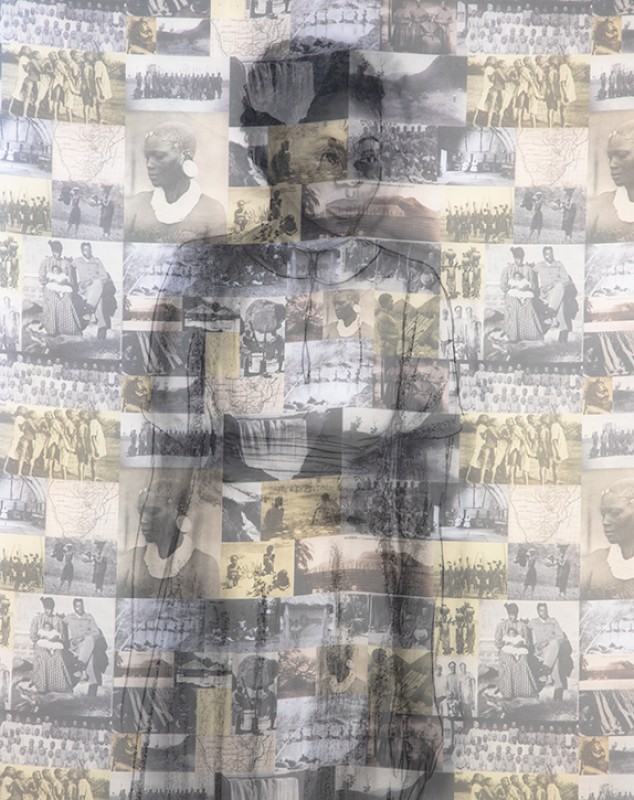

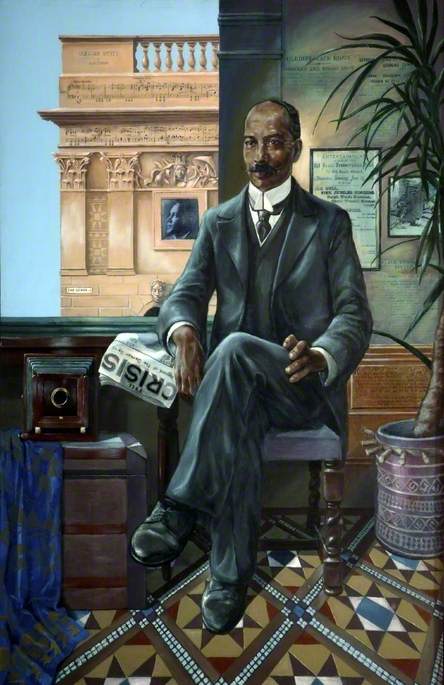

Often known as Queen Victoria's protegée or ward, Sarah lived a remarkable life, one which served to undermine pervasive imperialist attitudes in nineteenth-century Britain. Last year, the artist Hannah Uzor's portrait of Sarah, inspired by Silvy's photograph, was unveiled at Osborne House, the Queen's former residence on the Isle of Wight, thus disseminating Sarah's story to a wider audience.

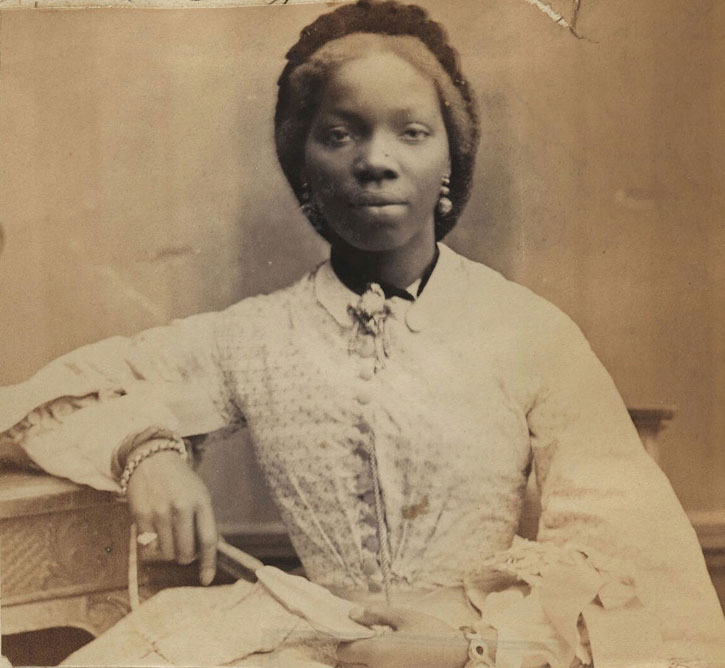

Only 19 years old when photographed by Silvy, Sarah stands tall as she gazes directly at the camera. Her typically Victorian dress features a large, billowing skirt and pinched corset. Next to her stands her husband, James Pinson Labulo Davies, a merchant and naval officer born to Yoruba parents, who had sought the Queen's approval for Sarah's hand.

Sarah holds a book – a sign of her education. On her left hand, rings are clearly visible, as she leans against the desk behind her. These photographs were taken one month after their wedding, a grand event which took place in Brighton on 14th August 1862, attracting large crowds and a flurry of media attention. Despite being one month later, in Silvy's photographs, Sarah wears her wedding dress.

Taken in Silvy's Porchester Terrace studio not long before the newlyweds travelled to Sierra Leone, these staged photographs were possibly intended to be distributed as cartes de visites, which Silvy produced for his wealthiest clients. This recently developed technique was based on the idea of taking six or eight small portraits, in several different positions and poses, on one glass negative. The sitters would then select from the results.

The fact that Silvy, the most fashionable portrait photographer in London, took the pictures himself demonstrates their elevated status in society. This stemmed from their close association with the royal family, many of whom had also been photographed by Silvy, with the exception of the Queen. Due to a devastating decline in mental health, Silvy's career was prolific but brief – he would spend the last three decades of his life confined in sanatoriums, eventually dying in 1910 as an obscure figure, but leaving behind some 17,000 photographs.

Although Sarah's story is unusual, historians such as Caroline Bressey have argued that her life – from captive girl to queen's accomplished ward – 'challenges our own assumptions about the status of Black women in Victorian Britain and their experiences of race and racism.'

Like Bressey, the historian David Olusoga points out that Sarah's privileged position in British royalty did not preclude her from experiencing racism in Britain where, from the mid-1800s, theories of social Darwinism and scientific racism had been developing. According to Olusoga, Sarah's time in Britain was 'buffeted and shaped by the profound contradictions and confusion about race' held by both the Queen's courtiers and her subjects, despite the fact that Parliament had enacted the Slavery Abolition Act in 1833 and Sarah had been brought to Britain by the naval captain Frederick Forbes in an anti-slavery mission.

Aina (Sarah Forbes Bonetta, later Davies) (1843–1880)

1862

Camille Silvy (1834–1910)

Born 'Omoboa Aina' in a region now known as Nigeria, Sarah was thought to be a princess of a Yoruba dynasty. Little is known about her parents, but Forbes claimed that they were killed during the Okeadon war of 1848 when Sarah was only five years old. Held captive by King Gezo of Dahomey, she was given to Forbes as a diplomatic 'gift' for Queen Victoria.

On her arrival in England, she was given the name 'Sarah Forbes Bonetta', after HMS Bonetta, on which Captain Forbes had sailed. In 1850, she was presented to the Queen at Windsor Castle. On 9th November, the Queen recorded in her journal: 'She is seven years old, sharp and intelligent and speaks English.'

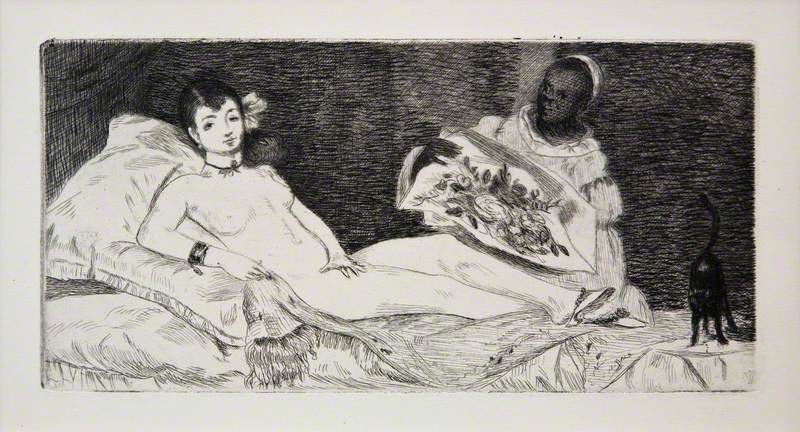

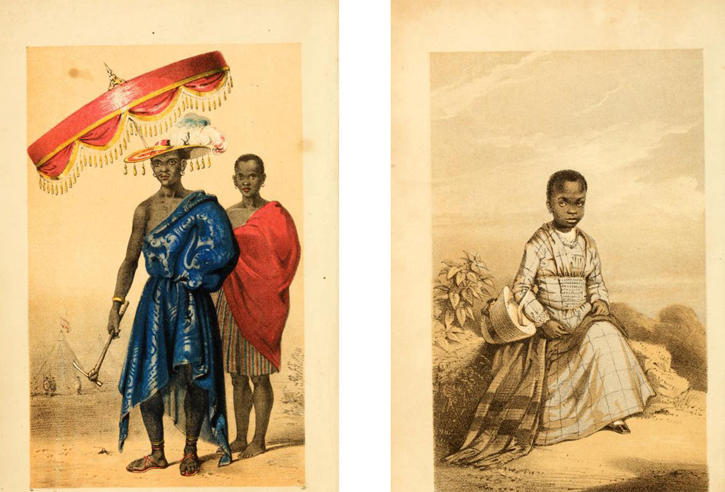

The next year, illustrations of King Gezo and Sarah as a child were published in Forbes' book, titled Dahomey and the Dahomens: Being the Journals of the Two Missions to the King of Dahomey and Residence at his Capital in the Years 1849 and 1850. In this widely read publication, Forbes adopted the pseudo-scientific terminology of phrenology to describe Sarah, examining in detail her intelligence and appearance.

Illustrations from 'Dahomey and the Dahomans'

1851, by Frederick E. Forbes, published by Longman, Brown, Green, and Longmans

Sarah had been briefly educated in Freetown, Sierra Leone, until she returned to Britain in the late 1850s, living in Brighton under the care of Miss Sophia Welsh. After her marriage, Sarah and her husband moved to Sierra Leone, but returned again to Britain in 1867, alongside their eldest daughter, named after Queen Victoria, who became her godmother. Not long after, Sarah became seriously unwell, eventually developing tuberculosis, for which there was no cure at that time.

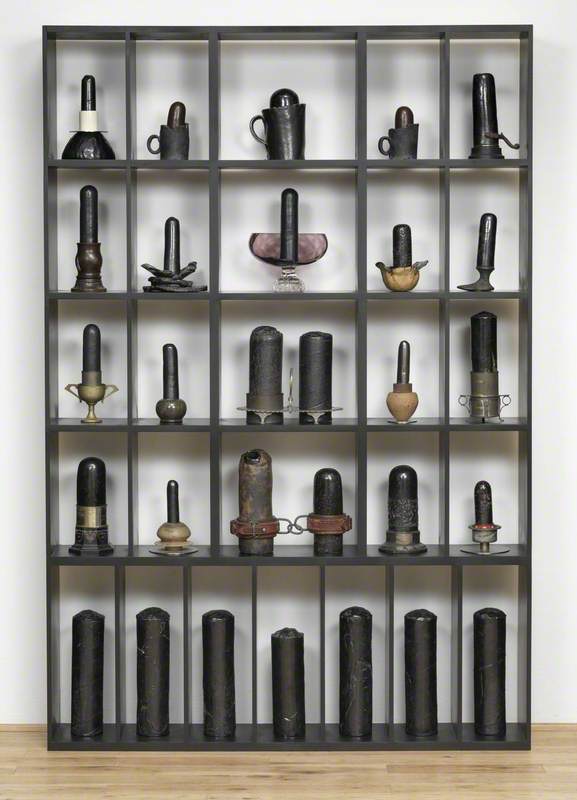

She had moved to Madeira where it was believed the warmer climate would restore her to good health, but unfortunately she died in 1880, aged 37. Her daughter was protected and supported by the Queen, who provided her with an annuity and paid for her education at Cheltenham Ladies College. Later in life, Victoria would became friends with the Black British composer, Samuel Coleridge-Taylor.

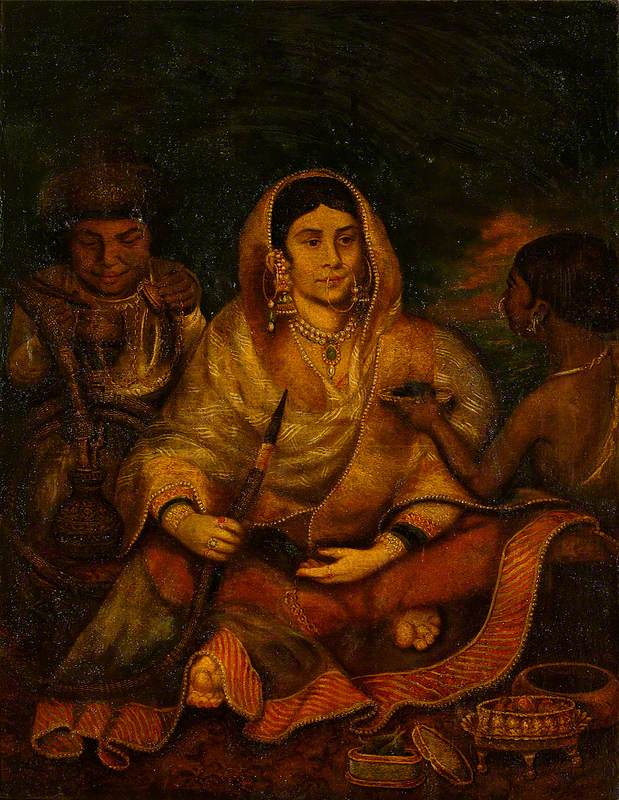

Arrival of Queen Victoria and the Duke of Wellington at St James's Palace

1851

Eugène Louis Lami (1800–1890)

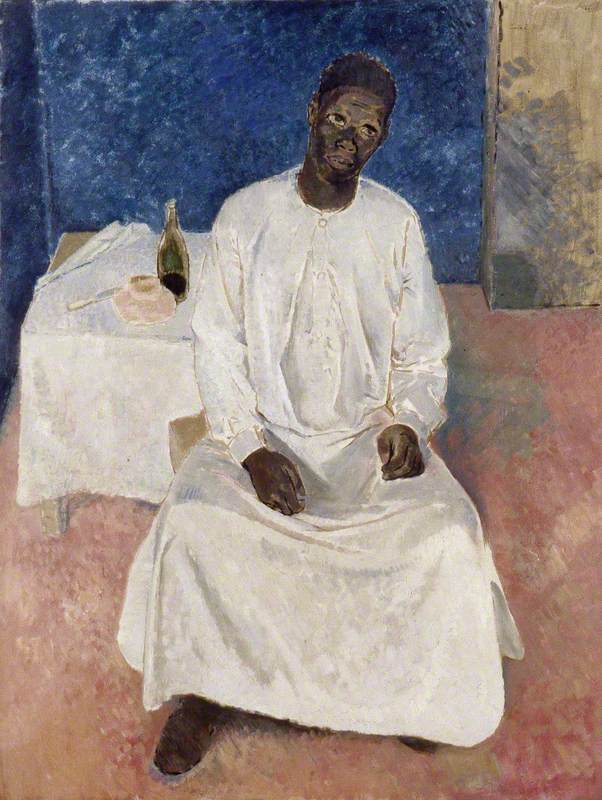

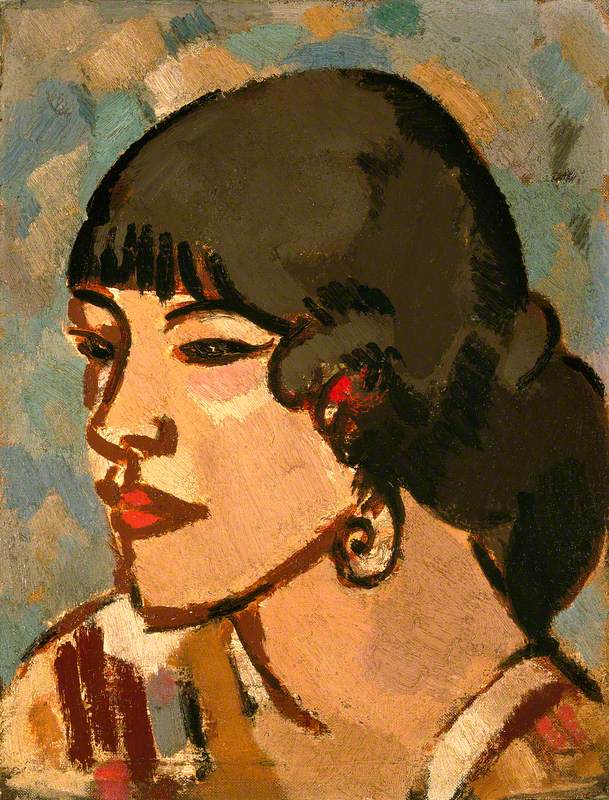

In honour of Black History Month 2020, Uzor's portrait of Sarah Forbes Bonetta, commissioned by English Heritage, was installed at Osborne House, the seaside residence of Queen Victoria. Based on the Silvy photograph, the painting brings Sarah to life in her white wedding dress, which is contrasted to the turquoise background. This painting, amongst others planned by English Heritage, forms part of the charity's aim to commission portraits of previously neglected Black figures associated with its historic sites.

Aina, Sarah Forbes Bonetta Davies (1843–1880)

2020

Hannah Uzor (b.1982)

More recently, Bristol Museums have announced that a series of photographs by the artist Heather Agyepong – inspired by the life of Sarah Forbes Bonetta – will go on display.

For @BRSphotofest we are presenting 'Too many Blackamoors' by Heather Agyepong @heatha_a in our Enlightenment Gallery. Taking its title from a quote by Elizabeth I, the series is inspired by Queen Victoria's West African godchild, Lady Sarah Forbes Bonetta. See for real soon. pic.twitter.com/aerLiSChIS

— Bristol Museum & Art Gallery (@bristolmuseum) April 9, 2021

Beyond the visual arts, Sarah Forbes Bonetta's story continues to inspire other cultural forms. Janice Okoh's play The Gift opened at Stratford East in 2020. The satirical drama examines how 'colonialists wielded politeness like a weapon', and shows how well-meaning white people can be blind to issues concerning race.

To remember Sarah's life serves to challenge assumptions about Black individuals in Victorian society (it could even be seen to shine a positive light on Queen Victoria). But it is important to remember that Sarah endured intense scrutiny while in Britain; she was viewed by many as the subject of social experiment, the beneficiary of a 'civilising mission'. Because of her early death and the lack of documentary records in her hand, it remains the case that her life has been defined by others. As Olusoga says, 'her own voice is largely silent.'

Lydia Figes, Content Editor at Art UK

Further reading

Caroline Bressey, 'Of Africa's brightest ornaments: a short biography of Sarah Forbes Bonetta', Social & Cultural Geography, Vol. 6, No. 2, 2005

Joan Anim-Addo, 'Bonetta [married name Davies], (Ina) Sarah Forbes [Sally]', Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, 2015

David Olusoga, Black and British: A Forgotten History, 2016