Why Minneapolis Was the Breaking Point

Black men and women are still dying across the country. The power that is American policing has conceded nothing.

Photographs by Joshua Rashaad McFadden

Updated at 4:45 p.m. on June 12, 2020.

MINNEAPOLIS—Miski Noor watched just the first minute of the video of George Floyd’s killing before closing the tab and walking the two blocks to join the protests already forming at the scene. The days since have been filled with a maddening sense of déjà vu.

Noor had joined the Movement for Black Lives in 2014, after the fatal police shooting of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri. The 34-year-old activist’s first protest was that December, a demonstration that shut down the Mall of America during the peak of the holiday shopping season.

Noor soon became intimately familiar with the gruesome cycle: The police killed someone. Activists protested. Small reforms were won. The police killed someone else…

In Minnesota, St. Paul police killed Philip Quinn, a Native American man in the midst of a mental-health crisis, in September 2015. One week later, a Kanabec County Sheriff’s deputy killed Robert Christen, a white former fullback for the Wisconsin Badgers who was enduring a mental-health crisis of his own.* Two months after that, in November 2015, Minneapolis police killed Jamar Clark, a 24-year-old unarmed black man. Hundreds poured into the streets.

In response to Clark’s killing, protesters launched what would stretch into an 18-day occupation of one of the city’s police precincts. One night, a group of armed white supremacists showed up. One of the racists opened fire, wounding five of the anti-racist activists. Serving as a spokesperson for the protesters, Noor questioned why police hadn’t done anything to prevent the attack—after all, the activists had reported the threats they’d been receiving to law enforcement.

The next day, police 400 miles east, in Chicago, released a grainy dashcam video depicting a white officer opening fire upon a 17-year-old black boy. The officer shot Laquan McDonald 16 times. People across the nation took to the streets.

In July 2016, we all watched Philando Castile die on camera, shot five times at point-blank range by a police officer during a traffic stop in suburban Minneapolis. A week later Mica Grimm, one of the leaders of the local Black Lives Matter chapter, traveled to the White House, where the then-mayor and then–police chief of St. Paul dressed her down in front of President Barack Obama—declaring the protests about Castile’s death “a disgrace.”

Exactly one year later, in the same city, came the death of Justine Damond, a 40-year-old yoga teacher who had called police to the alley behind her house because she thought she heard a woman’s screams. A police cruiser arrived, but when Damond approached, the officer got startled and shot her.

It would take two more years, but in April 2019, the local prosecutor finally secured a conviction of a police officer. But instead of a victory for the protesters, it was a cruel irony. The convicted officer was a Somali American, a black man, who was sent to prison for 12 and a half years after shooting and killing a white woman.

The following January, the most powerful newspaper in America endorsed the presidential campaign of Minnesota Senator Amy Klobuchar, who in eight years as a county prosecutor had never once brought charges against a police officer for misconduct. After losing, Klobuchar offered herself up as a potential running mate for Joe Biden, the presumptive Democratic nominee.

That she’d even be considered for either post—despite new reporting that suggests she put an innocent black teenager behind bars for life—underscored how unseriously much of mainstream politics still seemed to be taking the movement. In the years since Ferguson, the Minneapolis activists had helped elect progressive-reform types to both of the Twin Cities’ governments, and secured significant new police-oversight and accountability measures. But the pace of change remained infuriatingly slow.

Then, on Memorial Day 2020, came the cycle’s latest deadly churn: The police killed George “Perry” Floyd.

Once again, Noor felt a disorienting heaviness as thousands of fed-up people stormed the streets—first in Minneapolis, then across the country, and ultimately in cities around the world. The activists in the city where Floyd died are tired of meetings and town halls and promises. Enough, they’ve declared in word and deed.

“We have an elder here who said years ago that despair is a malfunctioning emotion,” Noor told me when we connected by phone between protests a few days after Floyd’s death. “Despair is what happens when grief doesn’t have somewhere to go.”

Seventeen-year-old Darnella Frazier was on her way out the door to a Memorial Day bonfire on the other side of town when her 9-year-old cousin made a request: Would Frazier walk her to a nearby store? Of course, Frazier replied.

She and her cousin were on their way back home, at the corner of 38th and Chicago, just south of downtown, when Frazier spotted a distraught man sprawled on the pavement. A pile of police officers was holding him down. At least one of the cops seemed to be on top of the man’s neck.

Frazier pulled out her cellphone and hit Record.

Within hours, the whole world had seen the video: Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin driving his knee into the neck of 46-year-old George Floyd, not only until Floyd died but for minutes after his life had been extinguished. What came next was a national crisis.

When I first sat down to begin writing this story, parts of many American cities were on fire and police officers in dozens of places were committing indiscriminate acts of violence—unleashing tear gas, rubber bullets, and worse—against the citizenry they had sworn an oath to serve and protect. Elected officials were pleading for peace as parts of their cities burned and the nation, watching in real time on television, asked “Why?”

I’ve spent much of the past decade reporting on the Movement for Black Lives, which holds as one of its chief aims a complete upending of American policing. That reporting has meant dozens if not hundreds of nights at street protests both peaceful and violent, helping to lead a Pulitzer Prize–winning team that created a national database of fatal police shootings, and writing a book-length chronicle of the movement’s birth.

For years, thousands of protesters have taken to the streets to demand a wholesale reimagining of the criminal-justice system. They have stated clearly that they believe American policing is inherently flawed. Black people in America, they argue, are chronically overpoliced and underserved. They are stopped and frisked while walking to the bodega and harassed while cooking out on their porches and patios. But when they are murdered? American police almost never deliver them justice.

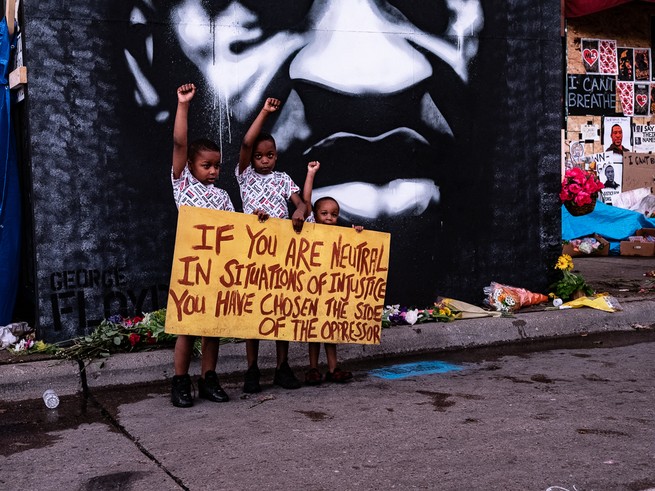

“We shouldn’t fear the police,” Alvin Manago, 55, who was Floyd’s roommate for the past four years, and still hasn’t been able to bring himself to begin packing up the slain man’s belongings, told me through tears as we stood next to the colossal memorial that has sprung up at the scene of the killing. “Like when I was a little kid—‘Oh, the police is here, they’re going to help us.’ That’s what I want us to believe and feel again.”

Though they sometimes diverge on tactical questions, the activists who make up the core of the movement desire to create, for the first time in our nation’s history, a reality in which black people aren’t routinely robbed of their livelihoods and lives by armed government agents. The aftermath of Floyd’s death has left many activists as encouraged as they’ve ever been that true change is on the horizon. Still, if the aim is a full recalibration of the American justice system, the task ahead remains monumental.

Public discussion about fixing the criminal-justice system often accepts as a premise that the path forward involves “reforming” thousands of individual state and local law-enforcement agencies and prison systems. But what if it doesn’t? What if the activists are right, and the solution is to dismantle American criminal justice and build something better? What might that look like?

The nation’s response to police killing after police killing has been to fire and criminally charge a handful of individual officers, mandate bias training that remains a relatively unproven remedy, and require body cameras that ultimately do little other than provide additional video evidence of the pervasiveness of police violence. (That is, when they are turned on at all.) The country collectively cares so little, five years after my former Washington Post colleagues embarrassed the FBI for its lack of federal data collection, that the agency still does not compile an accurate count of people killed by the police.

In May 2015, The New York Times Magazine wrote one of the definitive early profiles of the Ferguson activists. Its headline bore a straightforward message: “Our Demand Is Simple: Stop Killing Us.”

The killings continue unabated.

“I would never condone violence, ever,” says Elijah Norris-Holliday, a 24-year-old activist in the Twin Cities who has been organizing peaceful daytime protests and who was so distraught after seeing the video of Floyd’s death that he didn’t sleep for days. “But sometimes, when people feel like their voices are being ignored over and over and over, violence is the only other answer. They have to burn their own community down to get people to listen to them. We’re at a breaking point.”

Today’s young black activists have been beaten and arrested and harassed by local police officers. They’ve been doxxed by racist online trolls. They’ve had FBI agents show up at their homes. Some of the streets’ strongest voices and most potent symbols—Erica Garner, Darren Seals, Edward Crawford, Muhiyidin Moye—are now dead themselves.

“When civility leads to death, revolting is the only logical reaction,” Colin Kaepernick tweeted, as massive protests—both violent and nonviolent—spread across the country in response to Floyd’s death.

Kaepernick was banished from his job as an NFL quarterback and called a “son of a bitch” by President Donald Trump because he silently kneeled during the pregame national anthem. His act of peaceful protest—deeply unpopular with white Americans—was prompted by the July 2016 police shooting of Castile, the aftermath of which was broadcast live on Facebook by Castile’s distraught girlfriend. “The cries for peace will rain down,” Kaepernick continued in his tweet last week. “and when they do, they will land on deaf ears, because your violence has brought this resistance.”

For some, Kaepernick’s words may feel shocking. Yet they are the same words that echo through hundreds of years of black American activism, inescapable to anyone who bothers to pay attention. James Baldwin’s explicit allusion in the title of his 1963 masterwork, The Fire Next Time, is to coming riots in the streets. The Harlem Renaissance leader Langston Hughes cautioned ominously in the 1940s that “sweet and docile” black Americans may one day “change their minds.” The poem is literally titled “Warning!”

Decades earlier, there’d been the determined journalism of Ida B. Wells, whose Memphis newspaper was burned to the ground by white supremacists. Wells is best remembered for her crusading work in the 1890s, which not only documented the frequency of southern lynchings but also provided what we’d now consider data analysis in order to disprove the racist lie that lynchings were happening because black men had a particular lust for and inclination to rape white women. Less well known is that Wells also dispatched herself to the scene of cases of police violence, providing essential scrutiny of an equally American strand of homicidal impunity.

“Those who profess to favor freedom, and yet depreciate agitation, are men who want crops without plowing up the ground. They want the rain without thunder and lightning,” the former slave Frederick Douglass proclaimed in 1857. “They want the ocean without the awful roar of its many waters.”

“This struggle may be a moral one; or it may be a physical one; or it may be both moral and physical; but it must be a struggle,” Douglass continued, before arriving at a more widely quoted sentence: “Power concedes nothing without a demand.”

The power that is American policing has conceded nothing. Black men and women are still dying across the country as police unions continue to codify policies designed solely to shield their officers from accountability—such as rules ensuring that officers who kill can’t even be interviewed by investigators about it until their victims have been dead for days.

In the days since one of their own killed George Floyd, many American police officers have shamelessly brutalized the protesters whose chief demand is that the police stop brutalizing people.

Black Americans have grown so accustomed to pulling out cellphone cameras—who would believe us otherwise?—that we no longer risk having to rely on a single shaky video. Everyone pulls their phone out—which is why we can watch George Floyd die in full panoramic view.

In the days since the streets began burning, many have appealed to former President Barack Obama for intervention. Yet to suggest that Obama could silence the enraged screams of the streets is to fundamentally misunderstand the origins of the protests of recent years: They were, in part, a direct response to the perception among young black activists that his administration had failed to address persistent racial inequalities with adequate urgency.

“I voted for Barack Obama twice and still got teargassed,” the Ferguson activist Tef Poe said in 2014, after consecutive days of protests in which police deployed violence indiscriminately against demonstrators.

Obama did as much as, if not more than, any other American president to push for policing reform—yet as the former chief spokesperson for and political figurehead of the country whose police officers are carrying out the extrajudicial killings of black people, not even he can claim absolute moral credibility on these matters. Beyond that, though, is the reality that American policing as currently constructed is a matter of state and local government, and is not within the power of a president to single-handedly change. The symbolism of the first black presidency was potent. But the Obama-era reforms, ultimately, did not reduce the number of police killings.

The Obama Justice Department launched an unprecedented number of “patterns and practices” investigations to force reform in local police departments, but those investigations were launched in response to only the most egregious viral videos and most questionable police killings. The department’s Civil Rights Division, limited in both resources and statutory authority, could not reform 18,000 American police departments.

“The inability of the Civil Rights Division to take on anything but willful misconduct, as much as I love Obama and (Former Attorney General Loretta) Lynch and everyone else—we failed on that one,” Roy Austin, a former deputy assistant attorney general for civil rights and a key Obama adviser on policing, conceded to me.

Not one activist I’ve spoken with over the years has suggested that Obama does not get it. But, on an issue rife with impassioned activism, they note the former president’s cool calculation—his studied avoidance of any comment or action that could backfire. (Recall, for instance, the outcry when he weighed in on the 2009 arrest of Henry Louis Gates Jr.) Activists in Missouri observe that Obama never visited Ferguson, while allies of the former president note that his doing so could have prompted accusations that he was putting his foot on the scale of the investigation his Justice Department had launched into the police there; they also note that he dispatched then–Attorney General Eric Holder in his place. Obama has signaled for years that he does not see it as his ministry to lead protest chants.

“Obama has always said to me, ‘I was into community service, not community activism,’” the Reverend Al Sharpton, an adviser to both the Obama White House and George Floyd’s family, told me, by way of explaining the former president’s hesitation to insert himself more directly into these matters.

But in this arena too, Floyd’s death has spurred change. Those who have spoken with Obama in recent days say the former president is eager to use his platform to address American policing. Members of the Floyd family told me that they were impressed with the directness with which the former president tackled the subject in a recent online town hall, and some longtime activists are “increasingly satisfied” with Obama’s willingness to jump into the fray, Sharpton told me. After years of reluctance, the nation may be witnessing the birth of Obama the activist.

“We have seen in the last several weeks, the last few months, the kinds of epic changes and events in our country that are as profound as anything that I’ve seen in my lifetime,” Obama said during his address on June 3.

Even more frequent than public appeals to Obama are calls for a “new Martin Luther King Jr.”—someone who could “heal” the nation by persuading the thousands who believe their government is criminally apathetic to their humanity to join hands and sing “We Shall Overcome.”

These yearnings for a new Martin Luther King Jr. presume such a figure would have sufficient standing among white Americans—a group that collectively despised the original MLK while he lived—that he could succeed as a national unifier in a way the actual activist never did. This is such an outlandish assumption that one of the country’s most prominent young black comedians “joked” that white Americans are obsessed with finding the next Martin Luther King only so they can make sure to kill him, too.

Such suggestions also require the absolute confidence that, were King alive today, he would continue to advocate for precisely the same tactics in response to today’s injustices as he did in response to those of the 1950s and ’60s—a conclusion that presumes unknowable things about what a man who has been dead since 1968 would believe today. For all we know, King might by now have become so fed up by this nation’s persistent failure to address the injustices he made it his life’s work to expose that he too would be picking up a rock. Even saints have their limits. The real King, the one who lived and died fighting American white supremacy, openly declared that American police “make a mockery of the law.”

“While he did not want to see violent protests, he understood violent protests,” Martin Luther King III, the civil-rights leader’s son, told me last week. “Someone had their foot on the neck of George Floyd, and society has had its foot on the neck of black people. And black people and others now are saying that’s not going to happen anymore.” Yet when the living Martin Luther King quoted one of his father’s most famous statements—“A riot is the language of the unheard”—his Twitter mentions promptly filled with comments from white people eager to explain to him what his own namesake would have wanted at a time like this.

“When I saw the video, I cried, and I wanted to destroy everything in my house. That’s the truth,” Yolanda Renee King, 12, the sole grandchild of the slain civil-rights leader, said during a private moment with the Floyd family on the day of his Minneapolis funeral service. “We have been mistreated for 401 years! This is enough! I’m tired of this!”

Martin Luther King III and other activists I’ve spoken with in recent days share a unanimous belief that this time is different. Years into the movement, the potential for true progress may finally be at hand, in no small part because the same cycle of unabated violence that has infuriated black activists is finally, due to the unrelenting stream of video evidence, forcing many white Americans to wake up.

For decades, police violence and impunity had been problems that, polling suggests, only black people could see. The street uprisings of recent years—in Ferguson and Baltimore, Baton Rouge and Chicago—were propelled by black rage; although they had allies, those who flooded the streets in response to those incidents of police violence were primarily black men, women, and children. Now white eyes have been opened too.

A Monmouth University poll taken a few days after Floyd’s death found that 71 percent of white respondents deemed racism and discrimination “a big problem” in the United States—up 26 points from 2015. Nearly 80 percent of Americans—and 75 percent of white Americans—told pollsters that the protesters’ anger was either “fully” or “partially” justified. Forty-nine percent of white respondents said police are more likely to use excessive force against a black culprit than a white one, nearly double the 25 percent who acknowledged that fact in 2016.

“People finally see it. White people too,” Floyd’s younger brother Philonise told me as we talked in the lobby of the Minneapolis hotel where we were both staying. “My brother is going to change the world.”

When the day came for the first of Floyd’s funerals—his family held three services, in Minneapolis, where he died; in Fayetteville, North Carolina, where he’d been born; and in Houston, where he’d spent most of his life—I stood silently, flush against the back wall of the hotel meeting room where they had gathered until it was time to depart. Gianna, Floyd’s 6-year-old daughter, twirled in front of me in her white lace dress. Gwen Carr, the mother of Eric Garner, the black man killed by New York police in 2014, briefed Floyd’s family members about how difficult the coming hours would be.

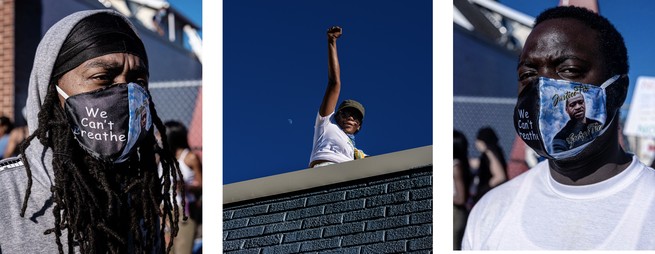

As we walked to the limos that had lined up outside the hotel, I asked Carr how many funerals like this she’d been to. She paused before softly responding: “You know, it doesn’t matter. This one will be different. Because this one was just like Eric.” Garner, like Floyd, had spent his final moments crying “I can’t breathe.”

After a short, largely silent drive, we all filed down the center aisle of the sanctuary at North Central University. The crowd, probably about 100 people, rose to its feet and sang “Total Praise,” a gospel staple. To attend a funeral in the midst of a global health pandemic was an act of protest in and of itself. Most attendees wore masks to prevent the spread of the coronavirus. About half were dressed in dark suits and dresses. The others wore T-shirts and hoodies that declared “I can’t breathe” and demanded “Justice for George Floyd.”

To the left of the stage sat the dignitaries. Martin Luther King III in the front row, Senator Klobuchar—who now says she regrets never charging any police officers—and Representative Ilhan Omar in the second. A few rows behind them was Clyde Bellecourt, 84, a White Earth Ojibwe who in 1968 co-founded the American Indian Movement, one of the most influential movements in the nation advocating for Native peoples. The movement had been launched in direct response to police violence against Native people in Minnesota—the available data show Native people are killed by police at the highest rate of any racial group—and Bellecourt had brought with him an eagle feather to present to the Floyd family, which is the Ojibwe tradition’s highest honor. I asked him what he thought of the video of Floyd’s death. “It’s nothing I haven’t seen before,” he told me. “Me and my people—” He paused. “We’ve seen a lot.”

To the right of the stage sat the celebrity mourners. In the first row, the rapper Chris “Ludacris” Bridges, the Hollywood producer Will Packer, and the comedians Tiffany Haddish and Kevin Hart. Just behind them sat the rapper Clifford “T. I.” Harris Jr., his wife, Tameka “Tiny” Harris, nestled into his shoulder. They, like so many, had been horrified by the video of Floyd’s death, and their attendance served as an acknowledgment that neither their money nor their fame insulates them from the possibility of a similar fate. Behind them sat the Reverend Jesse Jackson, noticeably slowed, two and a half years after announcing his Parkinson’s diagnosis. “They would have lied on George if it wasn’t for the camera,” he told me.

I found a seat about five rows back from the pulpit, across the aisle from the former NBA player Stephen Jackson, a close friend of Floyd’s who called him “twin.”

“I tell people all of the time, the difference between me and my brother Floyd is I had opportunity,” the former basketball player had explained at a protest earlier in the week. “So many of my brothers are so talented, and sitting in the ghettos and the hoods right now because they don’t have opportunity. And y’all wonder why we angry. We’re not just dying. It hasn’t been fair to us.”

Stephen Jackson sat silently throughout the funeral service. He leaned low in his chair, his eyes hidden behind sunglasses and much of his face tucked beneath the collar of a hoodie. But when the attorney Ben Crump vowed from the lectern that he would stop at nothing to procure justice for Floyd, Jackson sprang to his feet, spurring the entire room into thunderous applause.

The days since George Floyd’s death have been busy for Miski Noor. There have been protests to plan, and meetings to hold, and interviews to grant. But, Noor told me, the response across the city, country, and world has been inspiring.

The crowds filling the streets have been a racially diverse mix, and it seems that a fair percentage of those who have demonstrated are now willing to discuss more than body cameras and bias training. The coming days, weeks, and months, Noor and other organizers believe, will finally see a robust discussion about defunding and dismantling police departments, and ultimately abolishing American policing as it is currently constructed. Less than two weeks after Floyd’s death, officials in Minneapolis announced their intention to disband the city’s police department.

“We want justice for George Floyd, but we know justice isn’t enough,” Noor said. “That’s why we’re demanding bigger and bolder things. Now is the time to defund the police and actually invest in our communities.

“These systems were created to hunt, to maim, and to kill black people, and the police have always been an uncontrollable source of violence that terrorizes our communities without accountability,” Noor added. “Black communities have been and are living in persistent fear of being killed by state authorities.”

Many reformers, especially black reformers, have long viewed incremental policy changes as a way to reduce police abuse and killings in the short term while they work toward their true goal: fully remaking the entire criminal-justice system.

“We’re trying to grapple with one of the foundational sins of the country,” says Phil Goff, the executive director of the Center for Policing Equity, who has spent recent years working with police departments to implement vital reforms, expansive oversight, and new data-collection programs.

The movement to reimagine the criminal-justice system has not been defined by individual policy proposals, or even specific acts of injustice. The core ideology advanced by the black people in the streets is that the justice system—in fact, the entire American experiment—was from its inception designed to perpetuate racial inequality. The primary aim is to construct a world in which black Americans can live lives free of police harassment and violence, and are ensured justice when they are victimized—in other words, a world in which black people have access to the same protections that most white Americans already enjoy.

But in response to the mounting documentation of systemic bias—in nearly every study of the justice system, from traffic stops to prosecutions to sentencing to fatal police shootings to the application of the death penalty—“law and order” politicians of both parties and the leaders of local police unions continue to insist that the protesters are making it all up. These opponents, who hold a near-singular power to obstruct even piecemeal change, insist not only that the justice system is fair and equitable as is, but that all of this discontent is being fomented by opportunists and race-baiters who just like to say mean things about cops. “I don’t think that the law-enforcement system is systemically racist,” Attorney General Bill Barr said this week. “Painting law enforcement with a broad brush of systemic racism is really a disservice to the men and women who put on the badge, the uniform every day,” added Acting Homeland Security Secretary Chad Wolf. One of the most-read pieces on The Wall Street Journal’s website since Floyd’s death is a column headlined “The Myth of Systemic Police Racism,” written by a conservative commentator who has devoted much of her career to defending American policing from calls for change.

“One of the reasons, sadly, that we are seeing this violence and this rioting is that you have a lot of demagogues that want to use this incident of clear abuse by one police officer and they want to use it to paint every police officer as corrupt and racist,” Texas Senator Ted Cruz declared on Fox News as protests broke out across the country. The escalating violence was not the result of an unrepentantly racist system, Cruz said, but rather “everyone that is stirring up racial division,” meaning the anti-racist activists.

Racism is not to blame, the thinking popular among at least some conservatives goes. It’s the people fighting racism who are the problem. If everyone could just stop talking about all of this stuff, we could go “back” to being a peaceful, united country. No one seems to be able to answer when, precisely, in our history that previous moment of peace, justice, and racial harmony occurred.

* This article previously misspelled Robert Christen’s name and misstated the affiliation of the officer who killed him.