When John Abraham began to lose his mind in late 2019, his family immediately feared the worst. Abraham had enjoyed robust health throughout retirement, but now at 80 he suddenly found himself struggling to finish sentences.

“I would be talking to people, and all of a sudden the final word wouldn’t come to mind,” he remembers. “I assumed this was simply a feature of ageing, and I was finding ways of getting around it.”

But within weeks, further erratic behaviours started to develop. Abraham’s family recall him often falling asleep mid-conversation, he would sometimes shout out bizarre comments in public, and during the night he would wake up every 15 minutes, sometimes hallucinating.

To his son Steve, the diagnosis seemed inevitable, one which all families dread. “I was convinced my dad had dementia,” he says. “What I couldn’t believe was the speed at which it was all happening. It was like dementia on steroids.”

Dementia is not just one disease – it has more than 200 different subtypes. Over the past decade neurologists have become increasingly interested in one particular subtype, known as autoimmune dementia. In this condition, the symptoms of memory loss and confusion are the result of brain inflammation caused by rogue antibodies – known as autoantibodies – binding to the neuronal tissue, rather than an underlying neurodegenerative disease. Crucially this means that unlike almost all other forms of dementia, in some cases it can be cured, andspecialist neurologists have become increasingly adept at both spotting and treating it.

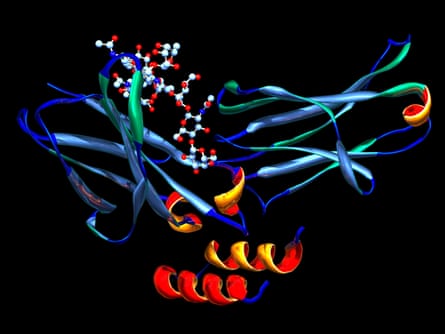

At the John Radcliffe hospital, University of Oxford, neurologist Sarosh Irani is one of the world’s leading experts in treating neurological conditions caused by a malfunctioning immune system. When Abraham was admitted under his care in early January 2020 following a seizure, Irani soon realised that the source of his problems was an autoantibody which targeted a protein in the brain named LGI1.

The main telltale clue was the speed of onset, one of the key distinguishing features of autoimmune dementia. “The symptoms usually come on very quickly,” Irani says. “Over a few weeks or months, patients develop memory problems, and change their behaviour and personality. Patients with neurodegenerative forms of dementia can develop movement disorders or seizures, but this typically happens later in the illness once degeneration has set in. In autoimmune dementia, these are early problems.”

Abraham underwent a treatment called plasma exchange, which aims to wash the blood of the disease-causing antibodies. The impact was almost instant. “For me it caused a complete transformation, in one or two days,” he says. “My family came in to see me in the hospital, and they just looked at each other in amazement.”

Such dramatic improvements are often reported as soon as treatment – which can also include steroids and other immunotherapies – begins. “Patients can go from being in a nursing home, unable to communicate, to returning to work, being able to drive again,” says Eoin Flanagan, a neurologist at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, one of a handful of centres in the world along with Irani’s research group, that is actively studying autoimmune dementia.

This is one reason why the condition, though rare – Mayo Clinic neurologist Sean Pittock estimates that it makes up less than 5% of all dementia cases – is so important to identify. The data available suggests that it is often missed. Among autoimmune dementia patients who were successfully treated at the Mayo Clinic between 2002 and 2009, 35% had been initially misdiagnosed with either Alzheimer’s or Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease.

“A lot of patients over 60 are misdiagnosed,” says Flanagan. “That’s a concern because if you miss these cases, you’re committing them to a presumed neurodegenerative course when they could respond to immunotherapy, and their symptoms resolve.”

But autoimmune dementia is also an illustration of a broader trend. Over the past 15 years, treatable diseases have been identified across an entire spectrum of neurological illnesses from epilepsy to multiple sclerosis and psychiatry, all caused by autoantibodies binding to different parts of the brain and central nervous system.

“It’s become one of the most exciting areas of neurology,” says Irani. “There are subgroups within all these illness groups that have very treatable diseases. If you’re a dementia doctor, a small percentage of your patients will have this condition, the same if you’re a psychiatrist or a multiple sclerosis doctor. And with these patients you can actually directly treat the underlying cause by suppressing the immune system.”

The rise of treatable neurology

In October 2019, another patient was admitted to the John Radcliffe hospital.Pippa Carter, aged 19, had just begun an English literature degree at the University of Leeds when she noticed that her vision seemed to be strangely distorted.

“I would be in lectures and I was really struggling to focus with my eyesight and with concentration in general,” she says. “I was trying to audition for a university play, and I had to stop because I couldn’t really read at all. Initially, I thought it was just nerves because I was starting a new chapter in life.”

Within weeks, she found herself unable to get her words out properly, before she was taken to hospital after suffering a large seizure. Just like Abraham, it was the speed of her decline which alerted doctors to a potential autoimmune cause. “Within a week she was hallucinating, shouting things,” remembers Irani. “In her hospital room, which she was in for several weeks, she drew these bizarre childlike pictures on the wall, like the sorts of things a four-year-old would draw. It was like something was causing her to regress in her behaviour.”

Carter was suffering from a neuropsychiatric syndrome caused by an autoantibody binding to the brain’s NMDA receptors, proteins which play a key role in learning and memory formation. Soon after she began treatment, first with steroids, and then an immunotherapy called rituximab, she began to improve. Now more than a year on, she is hoping to resume her university studies soon.

Since 2004, scientists have been steadily discovering the autoantibodies behind these various neurological conditions, making it possible for clinics to test for them. Irani says that so far they have discovered approximately 25, with one or two new autoantibodies detected every year. “There are probably many more out there still,” he says. “We’re not at the tip of the iceberg, but I think we’re probably nowhere near the base either.”

Precisely what stimulates the body to produce these autoantibodies remains unclear, but it is thought that there can be a variety of environmental triggers ranging from viral infections to tumours, along with an underlying genetic susceptibility.

Due to the number of patients who can be successfully treated, specialists are looking to raise awareness of the importance of keeping an eye out for them. “It’s really a not-to-miss set of conditions,” says Irani. “Our clinic runs a diagnostics lab where we receive UK-wide samples for many of these diseases. One in 100 are positive, and these patients clearly get better with steroids and similar medications.”

There are signs that the interest is growing. In November 2019, data was published from the first clinical trial looking at the effectiveness of different treatments for patients with a type of epilepsy caused by LGI1 autoantibodies. Two more trials are under way looking at new experimental therapies aimed at trying to stop the body from producing these damaging antibodies.

Irani is hoping that this will yield many benefits in years to come. “There’s definitely an under-recognition of these conditions,” he says. “But as the field continues to expand, there will be more and more of these patients who get picked up. I’m sure that if you look hard enough in acute psychiatry wards, and in nursing homes, there are patients out there with treatable conditions who are being missed.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion