Introduction

May is Mental Health Awareness Month in the United States. At The Trevor Project, we are well aware of the many struggles endured by LGBTQ youth. Through our pivotal work in suicide prevention, we come face-to-face with the fact that millions of LGBTQ youth are at risk for suicide and other poor mental health outcomes.1 However, many LGBTQ youth show incredible resiliency,2 and there are numerous protective factors that may promote wellness for these youth. The existing research shows that there is enormous opportunity for LGBTQ youth to thrive. This brief provides a summary of existing research on resilience among LGBTQ youth and, in line with Trevor’s life-saving mission, suggests ways that individuals and groups can enhance protective factors to foster positive development for LGBTQ youth.

Understanding Resilience

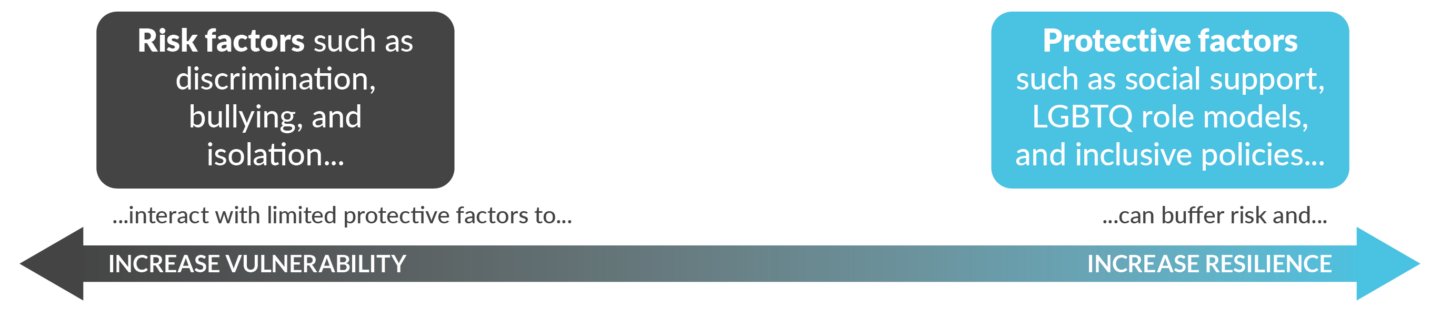

Resilience involves the ability to overcome adversity and can be facilitated by the presence of protective factors that reduce the negative impact of challenges and risk factors. For LGBTQ youth, risk factors such as stigma, discrimination, victimization, and rejection may make them vulnerable to experiencing a range of outcomes such as anxiety, depression, and suicidal ideation.3 However, the presence of known protective factors can interact with risk factors to facilitate resilience. Resilience is not rare, and has been described as “ordinary magic,”4 as it arises from normal human adaptive abilities. Studies of resilience have consistently challenged negative assumptions about youth development, highlighting the ability of youth to thrive even in the face of adversity.4

Protective Factors in Action

Given the importance of protective factors in navigating through the challenging period of development from ages 13–24, we synthesize here some of the main research on significant protective factors for LGBTQ youth. Importantly, we also discuss what individuals and groups can do to foster increased resilience among LGBTQ youth.

| Protective factor | Research synthesis | Actions and impact |

|---|---|---|

| Social support | Social support is one of the most important factors for LGBTQ youth well-being.5 Support from parents and family,6–8 teachers,9 and friends and classmates10 are all influential in LGBTQ mental well-being. Moreover, having relationships with others who share in the lived experience of being LGBTQ provides an opportunity for youth to feel less alone. Building relationships with LGBTQ adults and peers, and also non-LGBTQ allies, increases resiliency among LGBTQ youth.11 LGBTQ youth who are particularly resilient actively seek and cultivate these relationships.11 | Friends, classmates, parents, family members, teachers, doctors, mental health professionals, and others can actively provide resources and emotional support for LGBTQ youth. In many situations, youth may not reach out directly. Through the recognition of potential hardships, identifying their individuals needs, and offering relevant support, LGBTQ youth lives can be saved.Youth who reported high levels of family acceptance were 2/3 less likely to report suicide ideation and suicide attempts compared to those with low family acceptance.7 |

| Role models | Access to LGBTQ or LGBTQ-supportive role models improves mental well-being among LGBTQ youth. Positive portrayals of LGBTQ people in the media help to reduce feelings of social isolation and invisibility. For example, research has found that portrayals of LGBTQ characters in popular media evoke hope and foster positive attitudes among LGBTQ youth.12 Additionally, LGBTQ politicians and comic book characters have been cited as positively influencing LGBTQ identity formation.13 Further, as the climate around sports participation among LGBTQ youth is becoming increasingly more inclusive,14 coaches of sports teams may also serve as positive role models to help youth navigate their sexuality and provide support.15 | The entertainment industry and youth- serving organizations, as well as LGBTQ and allied adults, can increase LGBTQ youth access to role models. Executives, writers, and other creators of media can do more to ensure that diverse LGBTQ experiences are represented. Particularly, positive portrayals of LGBTQ youth who are doing well are needed. Organizations can create mentorship programs that pair LGBTQ youth with LGBTQ or allied adults. LGBTQ individuals can also volunteer at local youth centers or with youth-oriented programming at LGBT Centers. Even without formal mentoring programs, LGBTQ individuals and allies can be there for younger LGBTQ people at work, within family settings, and even on social media by being visible. |

| Environment | Supportive environments positively impact the mental well-being of LGBTQ youth. Positive school climates have been found to improve mental health outcomes.10,16 Specifically, LGBTQ youth who attend schools with anti-bullying policies inclusive of specific protections for LGBTQ youth,10 who can use the bathroom that corresponds with their gender identity,17 and who can use their chosen name,18 report better mental health outcomes. Furthermore, LGBTQ youth attending schools with a Gender and Sexualities Alliance (GSA) showed lower psychological distress and more favorable school experiences.19 LGB youth residing in more supportive regional environments, including increased proportions of same-sex couples within the region, were found to have a 20% reduced risk of suicide compared to unsupportive environments.20 A stable and supportive home environment can also prevent homelesness in LGBTQ youth.21 | A supportive environment can be facilitated by anyone. School officials can support youth in the creation of GSAs, the establishment of all-gender bathrooms, and the implementation of comprehensive anti-bullying policies. Anyone can join efforts by showing public support for policies that protect LGBTQ individuals and rejection of those that do not. While there have been many LGBTQ issues addressed in local-, state- and federal-level policies in recent years, discriminatory policies remain and new legislation continues to be introduced that can harm LGBTQ youth.Transgender youth who were able to use their chosen name at either home, school, work, or with friends had a 56% decrease in suicidal behavior.18 |

| Coping | LGBTQ youth can also take actions to support their mental well-being. One mechanism is when youth carefully assess their personal, social, psychological, and financial safety in all contexts and use this information to make an informed decision about coming out as LGBTQ or not.11 LGBTQ youth also develop individual coping mechanisms. For example, although rejection and victimization may happen, LGBTQ youth often find ways to shape their future through personal decisions, such as staying or leaving home or exploring their gender expression in ways that feel safe to them.11 Finally, coping strategies, such as seeking out LGBTQ youth resources, are associated with,better mental health compared to other types of coping (e.g. imagining a better future).22 | Anyone can support youth in their coping strategies. Individuals who work with youth, including educators, counselors, and health professionals, can make it clear that their office is a safe space for youth by perhaps displaying affirming posters and LGBT-friendly paraphernalia. It may also be useful to help LGBTQ youth explore positive coping skills such as seeking out LGBTQ resources, practicing mindfulness, and talking to supportive individuals in their life.Almost 50% of LGBTQ youth selectively decide which parents and teachers and in what contexts they disclose their sexual orientation or gender identity.23 |

Looking Ahead

Future research should do more to acknowledge and identify positive factors in the lived experiences of LGBTQ youth in order to provide the knowledge necessary for improving their real-world outcomes. Currently, there is a dearth of studies that examine how LGBTQ youth experience life beyond their negative experiences. Research shows that LGBTQ youth are disproportionally impacted by poor mental health outcomes, yet many LGBTQ youth are resilient and thriving. By understanding not just what places LGBTQ youth at risk, but also what reduces their risk, we can better understand their experiences and support their mental health.

The Trevor Project is committed to leveraging our crisis services, peer support, advocacy, education, and research programs to better understand and foster resilience to support the mental health of LGBTQ youth. For example, our 24/7 TrevorLifeline, TrevorText, and TrevorChat can provide youth with high quality support in moments of crisis, while our peer-support network TrevorSpace offers a supportive environment as well as role models. Our education and advocacy teams work to improve school and community environments for youth through targeted trainings and promotion of inclusive policies. And our research team will also be increasing our focus on understanding resilience among LGBTQ youth through initiatives such as our national surveys of LGBTQ youth.

| References1. Kann L, McManus T, William H, et al. Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance — United States, 2017. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2018;67(SS-8):1-114. 2. Russell ST. Beyond Risk: Resilience in the Lives of Sexual Minority Youth. J Gay Lesbian Issues Educ. 2005;2(3):5-18. doi:10.1300/J367v02n03_02 3. Meyer IH. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychol Bull. 2003;129(5):674-697. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674 4. Masten A. Ordinary Magic: Resilience in Development. New York, NY, US: Guilford Press; 2014. 5. Liu RT, Mustanski B. Suicidal Ideation and Self-Harm in Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Youth. Am J Prev Med. 2012;42(3):221-228. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2011.10.023 6. Mustanski B, Newcomb ME, Garofalo R. Mental Health of Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Youths: A Developmental Resiliency Perspective. J Gay Lesbian Soc Serv. 2011;23(2):204-225. doi:10.1080/10538720.2011.561474 7. Ryan C, Russell S, Huebner D, Diaz R, Sanchez J. Family Acceptance in Adolescence and the Health of LGBT Young Adults. J Child Adolesc Psychiatr Nurs. 2010;23(4):205-213. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6171.2010.00246.x 8. Needham BL, Austin EL. Sexual orientation, parental support, and health during the transition to young adulthood. J Youth Adolesc. 2010;39(10):1189-1198. 9. Murdock T, Bolch MB. Risk and protective factors for poor school adjustment in lesbian, gay, and bisexual (LGB) high school youth: Variable and person-centered analyses. Psychol Sch. 2005;42(2):159-172. doi:10.1002/pits.20054 10. Kosciw J., Greytak EA, Zongrone AD, Clark CM, Truong NL. The 2017 National School Climate Survey: The Experiences of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer Youth in Our Nation’s Schools. New York: GLSEN; 2018:1-168. 11. Asakura K. Paving Pathways Through the Pain: A Grounded Theory of Resilience Among Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans, and Queer Youth. J Res Adolesc. 2017;27(3):521-536. doi:10.1111/jora.12291 12. Gillig T, T Murphy S. Fostering Support for LGBTQ Youth? The Effects of a Gay Adolescent Media Portrayal on Young Viewers. Int J Commun. 2016;10:3828-3850. 13. Gomillion SC, Giuliano TA. The Influence of Media Role Models on Gay, Lesbian, and Bisexual Identity. J Homosex. 2011;58(3):330-354. doi:10.1080/00918369.2011.546729 14. Griffin P. LGBT equality in sports: Celebrating our successes and facing our challenges. In: Cunningham GB, ed. Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity in Sport: Essays from Activists, Coaches, and Scholars. College Station, TX: Center for Sport Management Research and Education; 2012:1-12. 15. Iannotta JG, Kane MJ. Sexual stories as resistance narratives in women’s sports: Reconceptualizing identity performance. Sociol Sports J. 2002;19(4):347-369. 16. Hatzenbuehler ML, Birkett M, Van Wagenen A, Meyer IH. Protective school climates and reduced risk for suicide ideation in sexual minority youths. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(2):279-286. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2013.301508 17. Weinhardt LS, Stevens P, Xie H, et al. Transgender and Gender Nonconforming Youths’ Public Facilities Use and Psychological Well-Being: A Mixed-Method Study. Transgender Health. 2017;2(1):140-150. doi:10.1089/trgh.2017.0020 18. Russell ST, Pollitt AM, Li G, Grossman AH. Chosen name use is linked to reduced depressive symptoms, suicidal ideation, and suicidal behavior among transgender youth. J Adolesc Health. 2018;63(4):503-505. 19. Heck NC, Flentje A, Cochran BN. Offsetting Risks: High School Gay-Straight Alliances and Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender (LGBT) Youth. Sch Psychol Q. 2011;26(2):161-174. 20. Hatzenbuehler ML. The social environment and suicide attempts in lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth. Pediatrics. 2011;127(5):896-903. 21. Durso LE, Gates GJ. Serving Our Youth: Findings from a National Survey of Service Providers Working with Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Youth Who Are Homeless or at Risk of Becoming Homeless. Los Angeles, CA: The WIlliams Institute with True Colors Fund and The Palette Fund; 2012. 22. Toomey RB, Ryan C, Diaz RM, Russell ST. Coping With Sexual Orientation-Related Minority Stress. J Homosex. 2018;65(4):484-500. doi:10.1080/00918369.2017.1321888 23. Human Rights Campaign Foundation. 2018 LGBTQ Youth Report. Washington, DC https://assets2.hrc.org/files/assets/resources/2018-YouthReport-NoVid.pdf?_ga=2.92754269.1758005609.1558478278-1737775507.1556739719. |

For more information please contact: [email protected]