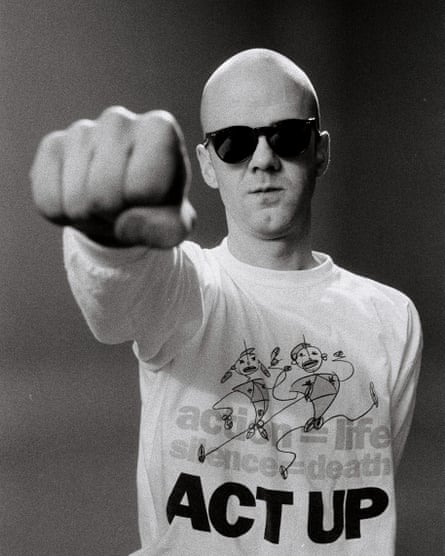

If activism is all about getting attention, then Act Up, you could say, screamed the loudest. As the Aids crisis deepened, this global network of campaigners used whatever tools they deemed necessary to wake the world up to their plight: “die-ins”, sprawling across the floors of corporations and churches; litres of fake blood chucked over the steps of town halls; a great many public snogs. And they had a thing for big condoms: a pièce de résistance was a huge pink sheath covering the obelisk on Paris’s Place de la Concorde.

This is the story of 120 Beats Per Minute. Winner of the Grand Prix at Cannes last year, the French film gives a fictionalised account of the country’s branch of Act Up (Aids Coalition to Unleash Power) in the early 90s, as young campaigners protested against government apathy at their plight.

The film’s director, 55-year-old Robin Campillo, was once part of the organisation and faithfully portrays the urgency of the group: they debate and argue, they protest and party, they cry, they have sex, they smoke and, inevitably, sometimes they die. For viewers whose knowledge of Aids movies are limited to Tom Hanks tastefully fading away in Philadelphia, it will come as quite a shock.

120 Beats Per Minute is all the more remarkable for the fact that many say the film portrays exactly what it was like. Will Nutland, who attended Act Up Paris meetings, says: “This feels like someone has just grabbed me and pulled me back.”

But the film is also, it has to be said, gloriously French, with everyone huffing and puffing away. Which leads to a question: while 120 BPM tells the story of the French movement – and the 2012 documentary How to Survive a Plague charts the actions of the original New York branch (founded by Larry Kramer in 1987) – what did Britons do as the Aids crisis deepened?

Lisa Power was at the very first meeting of Act Up London in late 1988. Her memories of the session, held in the basement of the now-defunct Gay and Lesbian Centre, are that it was “dimly lit” and had “cheap beer”. She remembers 15 or 20 people being present. “I’m pretty sure Peter Tatchell was there because one thing you can guarantee at the end of the 80s is that if somebody was founding something, Peter Tatchell and I would turn up to it.” In the 30 years since, Power has become a powerful LGBT advocate (she helped set up Stonewall). Tatchell is well known for his uncompromising activism, for instance with the protest group OutRage! Sure enough, Tatchell confirms he was there, but remembers things differently: “My recollection is that about 50 or 60 people were present. It was pretty crowded.”

A lot of Act Up’s history is only patchily recorded, not least for the awful reason that many activists have since died. Emotions about that time still run high. Most were animated by what Power calls “a blinding sense of urgency – because there were lots of people dying and they wanted to make a mark”.

Today, when in the affluent, white, western world at least, the Aids crisis has largely abated, it’s hard to recall the horror and confusion of the time – and the levels of prejudice. 120 BPM encapsulates this moment. Within the LGBT community, the ructions were as diverse as the people themselves. Tatchell, though, now manages to sum up Act Up London’s ethos: “It targeted anyone and everyone who was failing to address the HIV crisis.”

The group, as with all other chapters, specialised in direct, nonviolent action, aided by striking visuals. The aim, Tatchell says, was to “raise public awareness and put powerful people on the spot. It was also a psychological morale boost for people with the virus.”

In 120 BPM, activists chuck fake blood at medical researchers; the documentary How to Survive a Plague revisits a memorable moment when protesters placed a huge canvas condom over Senator Jesse Helms’s house. Act Up London’s actions seem a little less outrageous. “Paris were frankly a bunch of complete maniacs,” says Power with affection, while “there was a British sense of humour about the actions here”. She recalls one of the very first, outside Pentonville prison, where they blew up condoms and bounced them over the prison walls, to protest against the fact that prisoners weren’t allowed them. Tatchell was there, too, but again remembers things differently. “They weren’t blown up – they were catapulted over the wall.”

Nutland, meanwhile, helped set up Act Up Norwich (the group had branches across the country). They catapulted condoms over the wall of Norwich prison, only for their catapults to be confiscated by the police. “The policewoman who took them was called PC Dyke.”

Another activist, Ash Kotak, recalls an action involving the singer Jimmy Somerville, who was a vital figurehead, championing and funding the cause. He chained himself to railings at the House of Commons. “I asked him: ‘What was that like, Jimmy?’ He said: ‘I rather liked it.’”

Their collective humour, though, can’t mask the intensity of feeling of the time, and the fraught, divergent reactions it prompted. In 120 BPM, there is a scene in which a man, having helped his lover die, almost immediately has sex with another activist in the deathbed. “There was a sense of things you did that, looking back now, may have seemed quite weird,” says Nutland, “but when I watched that scene, I was like, yep! You fucked the grief out.”

Also ringing true in the film are ecstatic scenes where the characters go out clubbing; dancing to the era’s classic house music. Many activists said that it was just a bit of fun, but also a means of survival – intense fun for an intense time. It is one of the few facts that everyone agrees on.

Because there were downsides. Many activists recall Act Up being mired in arguments and discord. While the groups were ostensibly democratic, this could mean it was, at times, hard to agree on what to do. Tatchell says that the group benefited from its “accessibility and spontaneity”, but some are more ambivalent. “They would have said it was an open democracy, but it was pretty much a meritocracy, plus who shouted the loudest,” says Power. Others say it was shambolic.

In short, a British 120 BPM would look the same, but different. Despite this, there were subtle and important differences between Act Up in different countries. Britain was, everyone agrees, relatively lucky to have the NHS, which reacted well to the crisis – for this, and many other reasons, people never mobilised around the movement in quite the same way as in the US or France. It could even be just a matter of national temperament, the Brits opting to be less politicised and more focused on things such as providing care. However, most do believe that Act Up in Britain paved the way for more “respectable”, or at least organised, advocacy groups to make their case in the corridors of power. Tatchell calls them “the shock troops in the battle against HIV”.

The London branch fizzled out in the 90s, thanks to disagreements over their methods, on whether to take corporate money and where the fight should go next after treatment started to become available. A nadir for them, says Nutland, was when members trashed a stall set up by the Terrence Higgins Trust at an international Act Up meeting in Amsterdam in 1992 – they disagreed over whether lesbians should use dental dams during sex. “I also think one of the problems was that we never spent any time doing any medium- to long-term thinking,” he says. Everyone was just young and angry, he says. And many thought they would soon be dead.

Yet the Act Up London group was revived in 2012, facing new challenges: the rise of infection among certain minorities; the ongoing stigma for those infected; and the urgent need to save the NHS, as services face continued cuts.

The new Act Up still carries out actions – they dumped half a tonne of manure on the doorstep of Ukip’s headquarters after Nigel Farage said that people with HIV should be barred from entering the UK. “The gravity of the situation demands a grassroots, mischievous, creative, disobedient, fantastical group,” says Dan Glass, who pushed for the revival. “We have other groups, but we need to be on the streets.”

Others feel the fight is best fought elsewhere. Nutland has instead cofounded Prepster, which advocates the use of PrEP, a drug that has had startling success in cutting down rates of HIV infection. In a landscape transformed by the internet and social media, he argues, street actions still have a place, but it needs to be a lot more strategic, and fit alongside what else is happening.

Lisa Power tends to agree. But what even makes a good activist, anyway? She pauses. “You need to be a bit of a drama queen – but not too much.” Whether “too much” of a drama queen is a paradox, she doesn’t explain. But the activists in 120 BPM, scrapping and screaming for their lives, would definitely have something to say.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion