How will airlines rebuild their route maps after the coronavirus?

The sun is streaming through the windows and over rows of chairs. Several people are seated. One is reading, another looks at a phone. A teenager wears headphones to drown out the world. A plane sits outside, several more tails visible in the distance. A gate agent calls passengers for Flight 123 to New York. It's a travel day like every other in mid-summer, 2021.

Yes, 2021. That's when airline planners think commercial air travel will begin to look "normal" again worldwide after recovering from the novel coronavirus pandemic.

For now, airlines are in triage mode, pulling down thousands of daily flights from their schedules in somewhat orderly fashion as passenger numbers plummet. On April 2, the Transportation Security Administration (TSA) screened just 5% of the number of travelers that passed through checkpoints a year ago.

"This is 9/11, SARS and the Great Recession all rolled into one," is how Delta Air Lines CEO Ed Bastian described the crisis to employees at the end of March.

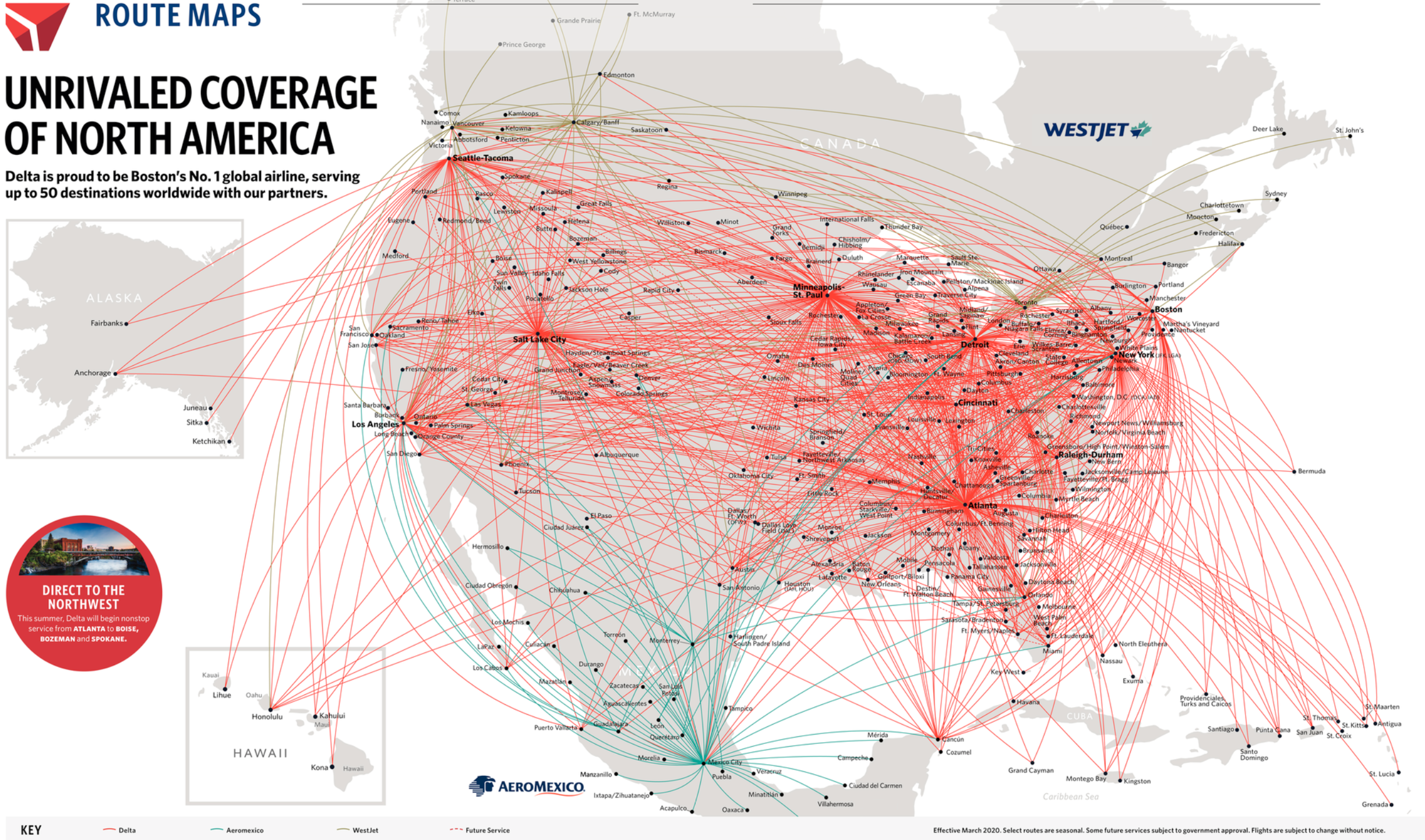

Airline maps, like the airlines themselves, will come out the crisis smaller and leaner than when they went in. It will be a hard reset, so to speak, with each carrier really reevaluating what works and what does not in their networks. Networks formed largely by stapling together the maps of six different carriers into today's "Big 3" U.S. airlines.

Get coronavirus travel updates. Stay on top of industry impacts, flight cancellations, and more.

Airlines will be smaller

"We're going to be smaller coming out of this. Certainly quite a bit smaller than when we went into it, and we'll have the opportunity to grow," Delta Chief Financial Officer Paul Jacobson told employees on March 19. The sentiment is shared by others in the industry.

How much smaller is the question. After 9/11, Delta flew 7% less capacity in 2002 than in 2001, but 12% less than in 2000 — the last full year prior to the attacks -- according the U.S. Bureau of Transportation Statistics data via Cirium. But, as Bastian said, the COVID-19 crisis is worse than 9/11 and the cuts will be deeper.

The $2 trillion CARES Act aid package includes strings to ensure airlines maintain connectivity across the country. To receive the aid, carriers must keep serving all of the destinations they served as of March 1, though they are allowed to pare back schedules to as little as one daily flight to any city they previously served daily. That's one daily flight per destination, not per route.

In the short term, these pared-back schedules will likely look something like what United has done in Spokane (GEG). The Star Alliance carrier has cancelled four daily flights — to Chicago-O'Hare (ORD) and San Francisco (SFO) — and kept just flight between the eastern Washington city and Denver (DEN).

Multiply what United did in Spokane, effectively an 80% cut, across every city in America and you get a sense of the scale of potential service reductions.

Related: United Airlines CEO warns of a smaller carrier post-coronavirus

Fewer frequencies

Airlines are already slashing flights, or frequencies, while maintaining connectivity at their largest hubs. Travelers can still connect through major airports like Atlanta (ATL), Chicago and Dallas/Fort Worth (DFW), but with fewer — in many cases far fewer — flights to choose from.

It is much easier for an airline to fill a plane at a hub, which benefits both from local flyers and from passengers coming and going from other cities.

Frequency reductions with continued connectivity through major hubs will feature in carriers' schedules as they recover. Cutting the number of "banks," specified periods of time when a number of flights are coordinated to arrive and depart to facilitate passenger transfers, is low-hanging fruit when it comes to rapidly cutting an airline's capacity but not its map.

How many flyers really want to take American's 5:30 a.m. departure from Washington Reagan National (DCA) to Charlotte (CLT)?

Related: American Airlines' summer schedule rebounds in some hubs, but not all

"In a slow recovery, I don't think you initially restore the primary hub to the same level of frequency as before," Kevin Healy, president and CEO of Campbell-Hill Aviation Group, an air service advisory firm, said in an interview. "You ensure that you have the necessary amount of network breadth and connectivity."

Healy knows what he is talking about. He led AirTran Airways' planning team during the recoveries from both 9/11 and the Great Recession. After 9/11, the airline initially cut its schedule by 20%, he said. It reduced frequencies but maintained service to every destination in its network.

In other words, AirTran maintained connectivity over Atlanta and its broader route network, while achieving capacity cuts simply by thinning schedules on many of its routes there.

Not all hubs will come back equally

Each airline has a set of hubs that are at the core of its map. For American, that includes Charlotte and Dallas/Fort Worth. At Delta, it's Atlanta and Detroit and, for United, it's Chicago and Denver. These are the backbones of their domestic flight networks that millions of passengers traverse every year.

The coronavirus recovery will be something of a back-to-hub-basics for airlines. At American this could mean that its Charlotte, Dallas/Fort Worth and Washington Reagan National (DCA) hubs, where management has focused new growth in since 2018, come back first.

"That's where American has been growing and will probably grow there [again]," said Brett Snyder, founder of the travel service Cranky Concierge and author of the Cranky Flier blog, in an interview. "It's the stuff around the edges that will go."

Asked what American's "edges" could be, Snyder pointed to Los Angeles (LAX) as a possibility. The hub has underperformed financially for the airline since its rapid build-up there after American's merger with US Airways in 2013. Executives even acknowledged at the outset of the coronavirus crisis that the carrier could permanently end service to China from the airport, a move that would be a setback for the carrier's long-held desire to build a gateway to Asia in Los Angeles.

Related: American could drop ambition of Los Angeles gateway to Asia in wake of coronavirus

"Think of DCA, LaGuardia, LAX and JFK as spoke-like in May," American vice president of network planning Brian Znotins told TPG on the airline's schedule next month. A spoke is a destination that only has flights to an airline's hubs.

Asked what the longer-term plans are for these hubs-turned-spokes, Znotins said: "One thing I've learned through this crisis is trying to forecast the pace and severity of the way things will be, no one can do that. We're just going to try to remain as flexible as possible so we can drive capacity where it's needed the most."

Some hubs may not come back at all. This was a repeated theme of past airline industry crises. US Airways dropped its MetroJet operation and Baltimore/Washington (BWI) hub after 9/11, and United and Delta closed hubs in Cleveland (CLE) and Memphis (MEM), respectively, following the Great Recession.

JetBlue Airways' Long Beach (LGB) base could fall into this category. The New York-based carrier has slashed what was once its main West Coast base in half in recent years. And earlier in March, the airline moved forward plans to end three more routes there amid its coronavirus-driven schedule reductions.

Related: JetBlue drops Oakland, shrinks Long Beach amid broader route shakeup

View this post on Instagram

Strategic hot spots

"You'll see many of the things which were labelled 'strategic,' in other words money-losing, pre-crisis on the chopping block," a senior airline planner told TPG. They were one of several high-level airline executives who spoke of potential map changes on condition of anonymity as they were not authorized to discuss the possible changes.

Strategic growth can refer to numerous moves carriers made in recent years. For Alaska Airlines, it could be some of the mid-continent flying from California added after its 2016 merger with Virgin America and already being pared back before COVID-19. For Delta, it could be its secondary transatlantic gateway in Boston. And for United, it could be re-evaluating some of its overlapping international services.

Los Angeles comes up frequently as an airport where the coronavirus could reshape airline service. American, Delta and United all call it a hub, though none of them controlled even a fifth of the airport's 88.1 million passengers last year, LAX data shows. Alaska and Southwest Airlines also maintain sizable presences there.

Who might cry uncle there is anyone's guess. So far, American has pared its LAX schedule the most in April, according to Cirium schedules. However, not all of the cuts being made by Delta, Southwest and United have been fully loaded into schedules. Delta is investing billions of dollars to rebuild Terminals 2 and 3 at the airport but benefits from two other western hubs. United sits in the No. 3 spot at LAX, where much of its flying overlaps with its strong Pacific gateway just up the coast in San Francisco (SFO).

Boston and Seattle are other hot spots of U.S. airline competition. Delta and JetBlue are facing off in Boston, while Alaska and Delta are duking it out in Seattle with American joining the fray at the 11th hour. Looking at the basics, Boston is core to JetBlue and Seattle is home for Alaska. Delta plays second fiddle at both airports and may focus more on its own core hubs if forced to retrench.

That said, Delta is not a carrier that backs down lightly. "Delta's a ruthless competitor," Healy says.

Related: Delta to emerge a much 'smaller' airline from coronavirus crisis

Spokes

Airlines' spoke routes are seen as less consequential to their maps post-crisis. The very nature of being a spoke — be it Delta's service between Indianapolis (IND) and Paris Charles de Gaulle (CDG) or JetBlue's flight between Buffalo (BUF) and Los Angeles — means an airline can maintain the breadth and depth of its hub-focused network with or without those so-called "point-to-point" routes.

Craig Jenks, head of the New York-based Airline/Aircraft Projects consultancy, has analyzed the market between Europe and the U.S. for years. He said that after previous slowdowns, U.S. airlines have repeatedly retrenched to serving major cities, like London or Paris, and partner hubs in Europe while dropping routes to secondary destinations, like Lyon (LYS), France. He anticipates a similar shift in transatlantic flying once the coronavirus crisis passes.

American, just days after TPG spoke to Jenks, published a summer schedule that suspends all of its seasonal routes to secondary European destinations. Now off the schedule until at least 2021 are the airline's planned flights to places like Berlin (TXL), Casablanca (CMN) — due to be its first ever route to Africa — and Prague in the Czech Republic (PRG).

The future of domestic spokes is an open question. Cutting them only moves the needle a little for airlines that are looking for double-digit reductions, but such routes are also not core to their network strategy.

Take for example Delta's focus city in Raleigh/Durham (RDU). All of the flights from the North Carolina airport to non-Delta hubs add up to about 50 daily departures in July. That's only about 10 fewer departures than the average bank at its Atlanta hub, according to Cirium.

Instead, Delta could cut one bank in Atlanta and achieve about the same capacity savings as chopping its Raleigh/Durham focus city.

The calculus for deciding which spokes get cut and which ones stay will likely be some kind of trade-off involving available aircraft — older jets are being retired early in large numbers — profitability, and market-specific sales relationships and recovery expectations.

"Airlines are going to ask, 'Do we really need to fly this?'" said one of the airline executives. "Everyone is going to contract. Hubs are going to be smaller... [and] airlines are going to be forced back into their core."

Related: It may be years until passenger demand returns to 2019 levels for US airlines