Christopher Tucker, who has died aged 81, was a pioneering special makeup effects artist for screen and stage who designed the face masks for John Hurt in the film version of The Elephant Man and Michael Crawford in the West End musical The Phantom of the Opera.

It was because of Tucker that the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences created an Oscar for best makeup in 1981 – a year after widespread criticism that his remarkable prosthetics skills had gone unrecognised with an award for The Elephant Man (1980).

David Lynch, who directed the film – about Joseph Merrick, renamed John in the film, a real-life 19th-century performer in a circus “freak show” – tried doing the makeup prosthetics himself, but was clearly out of his depth.

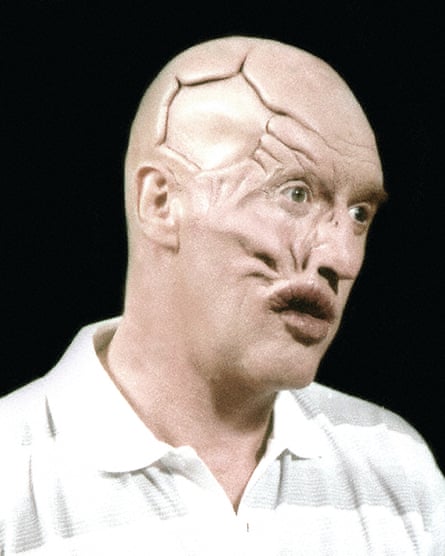

Just a week before shooting was due to begin, Tucker was hired. He began by working with photographs and Merrick’s skeleton, transported to his home from the Royal London hospital’s museum. “The deformity was severe,” said Tucker. “The normal average circumference around the head is about 22.5 inches. The Elephant Man’s was 36 inches. The neck was grossly deformed, giving him a collar size of 30 or more. It was a matter of transferring as much of that as we could into John Hurt.”

He worked painstakingly against the clock, at one time putting in a working “day” of 49 hours. The face mask comprised 15 overlapping sections, with the “joins” not obvious to audiences. “I didn’t want them to think about the makeup,” said Tucker. “I wanted them to watch the performance.” Lynch acknowledged: “Christopher Tucker saved the day.”

Creating the mask for another character with a disfigured face, the ghost who haunts the Paris Opera House in Andrew Lloyd Webber’s musical The Phantom of the Opera, opening at Her Majesty’s theatre, London, in 1986, highlighted the challenges involved in allowing the performer to function.

Layers of latex were applied to Crawford’s face, with two wigs, a radio microphone and contact lenses fitted before the vertical half-face mask was added. The ears, nose and mouth had to be kept clear and, to give Crawford a Rudolph Valentino look on the exposed side of his face – presenting the romantic aspect needed – Tucker designed extra prostheses to straighten his nose.

Not only was there discomfort and a three-hour makeup session before and after performances – eventually reduced to two hours – but Crawford could be in costume for 12 hours on days with matinee performances. He quickly learned to drink tea and soup through a straw.

Tucker received official recognition from the UK film world when Bafta made its first presentation of a best makeup award in 1983. The honour went to him, along with Sarah Monzani and Michèle Burke, for their work on the 1981 Canadian-French film La Guerre du Feu (Quest for Fire), a prehistoric fantasy. It included making dentures to snap on over the actors’ own teeth. “Primitive man’s teeth were rather different to modern teeth,” Tucker observed.

However, he was overlooked in the US again when the film won the best makeup Oscar but the rules allowed only two names to be attached to the nomination – Monzani and Burke.

He received other Bafta nominations, for best makeup and best special visual effects, for the 1984 gothic horror film The Company of Wolves. His tasks included transforming the actor Stephen Rea into a wolf as he clutches his face and rips off his own skin – a deliberately laboured and bitingly realistic scene with muscles expanding and contracting – as well as creating wolves bursting out of the mouths of characters.

Christopher was born in Hertford to Leslie Tucker, a solicitor, and Leila (nee Ison). After moving around various schools, he trained as an opera singer at the Guildhall School of Music and Drama in London.

With his bass voice, he performed character roles and grew interested in the makeup. For Verdi’s Rigoletto, he wanted a larger nose, so made one. When his talent became known in the TV and film world, his first makeup credit came on the big screen with Julius Caesar (1970), starring John Gielgud and Charlton Heston. He left his career as an opera singer in 1974.

Tucker showed a skill for ageing actors, from Derek Jacobi and others in the BBC’s 13-part I, Claudius (1976), to Ronald Pickup in the mini-series Einstein (1984). Pickup said the initially “frightening experience buried beneath [a] prosthetic” was leavened by Tucker’s black sense of humour.

This quality proved apposite when he designed the face of the obese bon vivant Mr Creosote, one of the characters played by Terry Jones in the 1983 Monty Python film The Meaning of Life. He also made masks for David Niven in Old Dracula (1974), Gregory Peck and Laurence Olivier in The Boys from Brazil (1978), Angela Lansbury in The Company of Wolves, and Daryl Hannah in High Spirits (1988).

Tucker was on the team that brought to life the Mos Eisley cantina bar scene, featuring various alien races, early in the first Star Wars film (1977, later retitled Star Wars: Episode IV – A New Hope). The humanoid Ponda Baba and a giant praying mantis were his creations.

Later, the Royal Shakespeare Company commissioned him to create the nose for Jacobi’s Cyrano de Bergerac (Barbican theatre, 1983) and the hump for Antony Sher’s Richard III (Royal Shakespeare theatre, 1984). He worked on Phantom of the Opera shows around the globe for 35 years.

A return to the world of opera came when he created the head and body parts for the Egyptian pharaoh of the title in Akhnaten (1983), by Philip Glass.

Tucker’s first marriage, to Marian Flint in 1971, ended in divorce. He is survived by his second wife, Sinikka Ikaheimo, whom he married in 2013 after more than 30 years together, and his brother, Lynton.