When Marjane Satrapi began drawing again, depicting the violence recently enacted by Iran’s Revolutionary Guards, she was so disturbed that she felt physical pain. “I get finger cramps when I have to draw them,” she shudders.

It is 24 years since Satrapi’s bestselling comic-book masterpiece, Persepolis, transformed western readers’ image of Iran. Her graphic memoir was told through the eyes of a cheeky, outspoken young girl growing up during and after the 1979 Islamic revolution, buying Kim Wilde cassettes on the black market, and trying to make sense of arrests, torture, the “morality police” and the carnage of the Iran-Iraq war, before being brutally uprooted to Europe, alone, aged 14, because her parents felt she would be safer there.

Millions of copies of Persepolis have been sold, making Satrapi one of the biggest-selling Iranian authors of all time and the first woman to be nominated for an animated feature Oscar for the hit film adaptation. Her cartoons were in demand from newspapers around the world, but she stopped drawing them in 2004, moving to other forms of storytelling and subject matter. She made five feature films, including the acclaimed 2020 Radioactive, about Marie Curie’s pioneering scientific research. But for years after Persepolis, the international press hankered after the expressive face of her nine-year-old cartoon alter ego. “Each time, they’d say, ‘But we want the little girl.’ And I was like, ‘The little girl has grown up,’” she says.

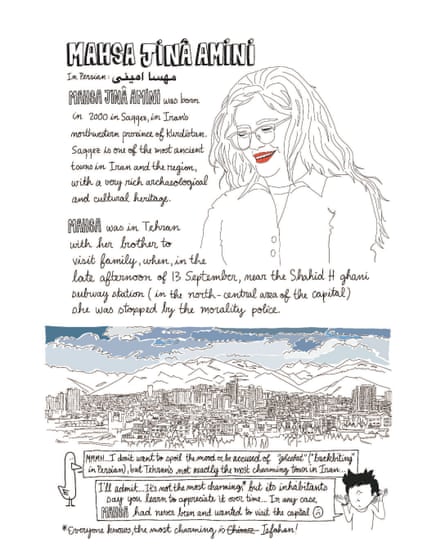

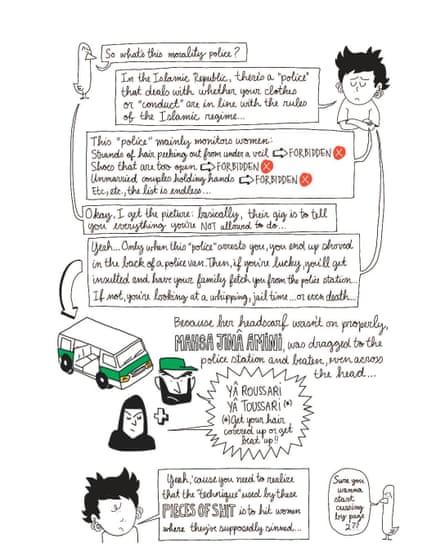

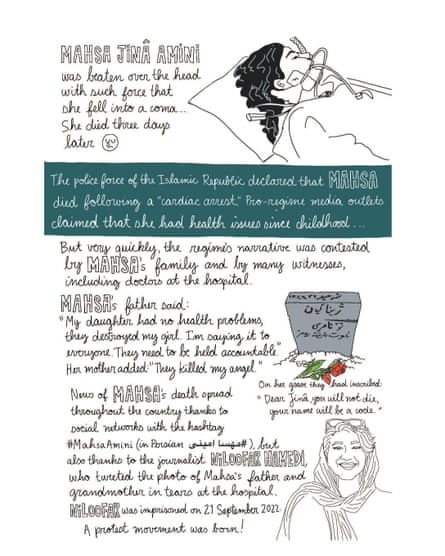

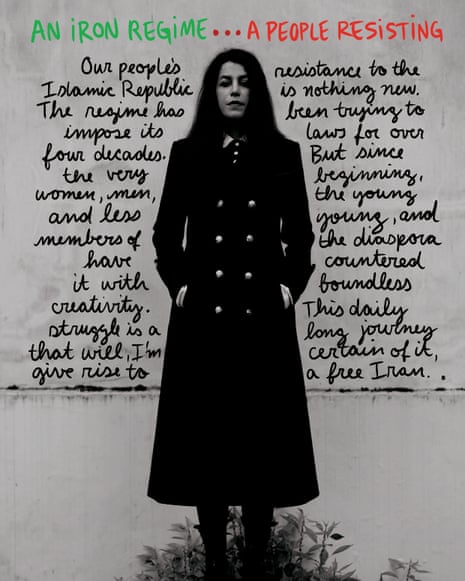

Now, Satrapi has – exceptionally – returned to her drawing board to tell a story she feels is so important that only the comic-book narrative will work. Woman, Life, Freedom, coordinated by Satrapi, is a collective book by 17 Iranian and international comic-book artists, working with Iranian academics and researchers. They have come together to tell the story of how the death in custody of Mahsa Amini, a 22-year-old Kurdish-Iranian woman detained for allegedly not properly wearing the Islamic headscarf in 2022, has led to the largest wave of popular unrest in recent years in Iran. The Iranian authorities’ insistence that Amini died from natural causes, amid her family’s allegations that she was beaten, sparked protests against the clerical establishment that have grown into a broad movement to challenge the theocracy that has ruled Iran since 1979.

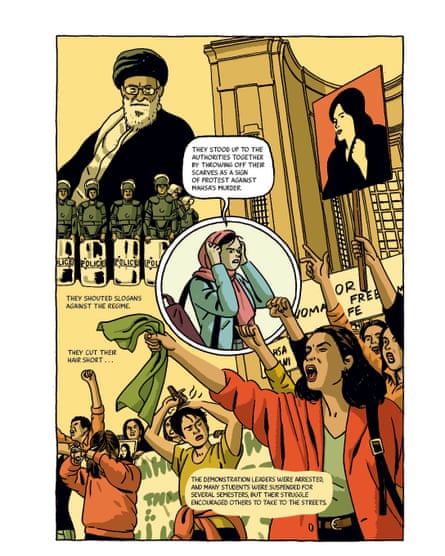

From images of crowds chanting the slogan “Woman, Life, Freedom”, to women removing their mandatory headscarves, and of the regime’s brutal crackdown and the young Iranian men who have been executed after taking part in the protests, the book honours the dead and depicts a young generation’s protest, its deep-rooted desire for freedom and equality.

“I call it a revolution,” Satrapi says. “It’s not a revolt, it’s not a movement, it’s a proper revolution. I’ve said it many times and nobody says the contrary: I think it’s the first really feminist revolution … and it is supported by men.”

Sparking a revolution:

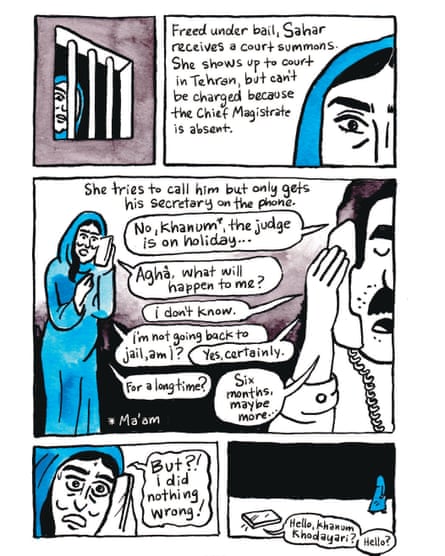

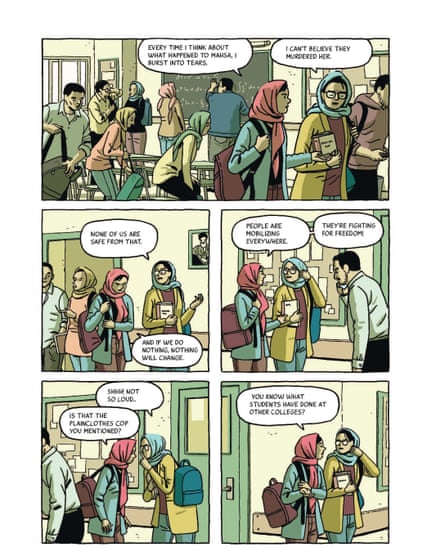

Bahareh Akrami & Farid Vahid

The aim of making a comic book was twofold. First, “to explain things for the non-Iranian audience”, she says. The economic, political and social context of the protests in Iran is told through the everyday stories of the young women and men who have been demonstrating, from male and female students defiantly standing together in university canteens, to pupils mysteriously falling ill from toxic gas in girls’ schools, which many feared was a deliberate state tactic to keep them at home and stop them demonstrating. The book also shows the prison sentences and hangings meted out amid the bloody crackdown, inspiring yet more demonstrations, which have crossed social class and gender, spreading across the country.

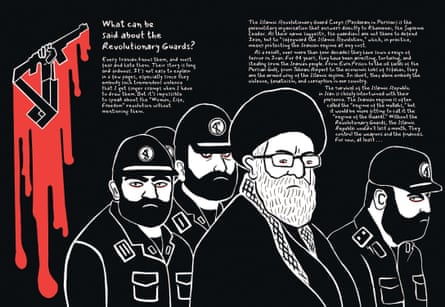

But Satrapi also wanted to reassure young Iranians that they were being heard and supported by the world outside. “If they kill you and the whole world doesn’t care, how is that? This is the whole thing I’m asking: just recognise this.” Satrapi insisted on making the book available online in Persian for free. She says the involvement of major international names in comic-book art, such as Joann Sfar and Paco Roca, working alongside Iranians including Shabnam Adiban, was also intended to send a message of solidarity. Satrapi, who created the cover art of women and men with their hair in flames, and a double-page spread on Iran’s Revolutionary Guards, sees the artists who have taken part as a kind of “international cultural brigade”, helping the cause through art.

Satrapi, 54, is based in Paris, and hasn’t returned to Iran since the success of Persepolis. She calculates she has lived only 18 years of her life in her home country. Woman, Life, Freedom doesn’t overlook the difficult position of the vast diaspora of about 8 million Iranians living outside Iran, many of whom have supported protests. Iranians abroad have no place telling people what to do, she says. All they can do is amplify the message coming from the streets of Iran, not rewrite or dictate it. “We can be the loudspeaker, that’s all,” she says. “If we think that we are anything else but a loudspeaker we better not talk – it’s a matter of decency.”

Satrapi argues that her comic-book art has always had one central aim: to humanise Iranians. She abhors what she calls “a hidden racism” in the west that views Iranians as people who are not culturally suited to human rights. She says western film festivals love Iranian cinema when it depicts a country “stuck in the dark ages”, with shots of “a hillside and a donkey”. “A tree … A woman … An apple,” she whispers dramatically. “Fuck that, we live in cities, we have very complicated problems.” Persepolis, in its honesty about messy family relationships, with images of city life and leftwingers driving Cadillacs, was ultimately about making the reader reflect – “Oh, they’re actually human beings like us,” she says. This new book, too, is about “being considered a human being, and not just this axis of evil, these fanatics. Because the government isn’t representative of us.”

When Satrapi heard news of Amini’s death in custody and the start of the protests, she was staggered by the differences between today’s more educated younger generation and her own. “I thought, ‘My god, they are fucking fearless,’” she says.

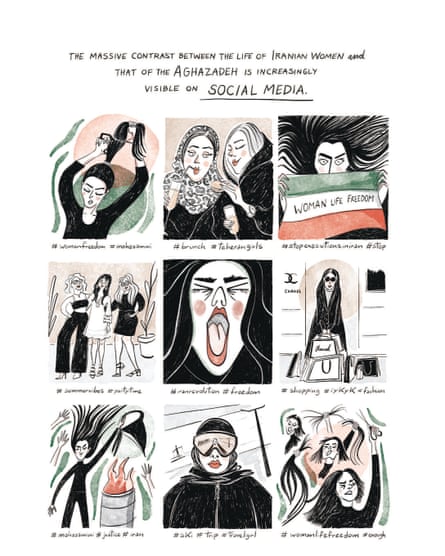

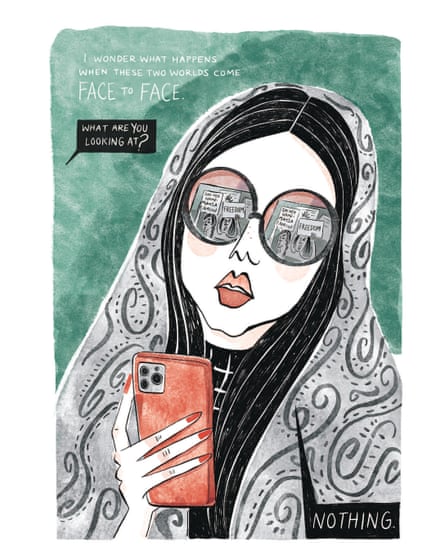

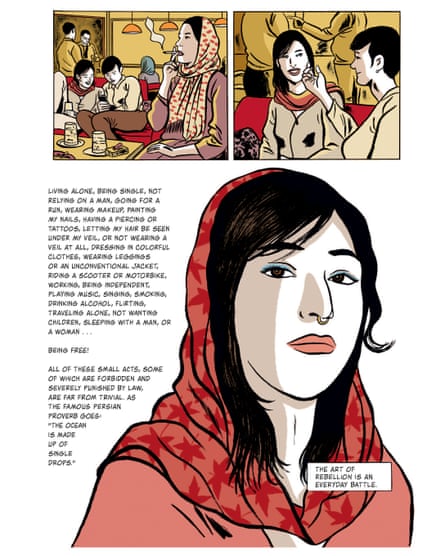

Her own generation, traumatised by the Iran-Iraq war and terrified of arrest by the “morality police”, were always mentally preparing to be taken political prisoner, Satrapi says. Living a kind of split life, they would sneak out to buy black-market western videotapes from men with suitcases in Tehran. They had one identity inside the home and another outside in the street. By contrast, “today’s youth has said, ‘Fuck it, we don’t want to live that way: inside and outside, I want to be me.’ And what they are asking, really, is to be able to wear what they want, to be able to sing what they want, to be able to write what they want, to have the freedom to think.”

“It’s really interesting from a sociological point of view. Because when I grew up, if you had a question, Mum and Dad would answer it – family beliefs went from one generation to the other. And it takes lots of courage and guts to say, ‘I’m not the education that I received, the beliefs they gave me: I don’t want them.’” This generation’s young people, she says, are connected to their peers. “They find their own solutions to their problems, discussing with kids their age, finding the answers on social media. It’s a break with tradition. It’s a break with family stories, because they make up their own minds … And, you know, human nature is made for freedom. With this youth, we might have better days.”

Feared and Hated:

Marjane Satrapi

The book is also about exposing the mechanisms of state violence. Since traditional media can’t get access to tell the story on the ground, and the small everyday acts of personal protest have dropped out of international headlines, the authors wanted to make them real through drawings. “When you’re a young Iranian person and you go out and do something as insignificant as taking off your scarf, as a girl, or, as a boy, wearing bermuda shorts, you can be stopped, beaten up, raped, go to jail,” she says. “And people have been killed, after which their parents protested, and then the parents were put in jail for five, six, seven years. And then the family’s lawyer who defended the cause also ended up going to jail for five, six, seven years. As soon as you open your mouth, you go to jail.”

Comic-book art was the most impactful medium for the project, Satrapi says. “Because the drawing is part of the writing. Instead of saying, ‘Oh, this girl was standing in the middle of the square holding her scarf and setting it alight while other people around her were supporting her’, you make a drawing and all of it is said … A drawing of an angry face looks the same, no matter your ethnicity, background, culture. So, on the emotional side, you can really nail the thing.”

But returning to the drawing board brought back what had been so difficult about creating her memoir two decades ago. “When I made Persepolis, I physically ached. Because you have to remember things. I had managed to put some of it away, and then, when you have to go and dig it out, it’s like a big shit pile. You’ve put it somewhere it doesn’t smell any more, and here you are shooting at it with a shotgun and the shit comes all over you. It’s smelly. Physically, it’s difficult … It literally hurts.” She pauses, takes a drag of her cigarette, and then sends herself up for sounding soft. “I sound like La Dame aux Camélias!” If Satrapi paid a price for Persepolis in being unable to return to Iran, she is resolute about never complaining. “It would be indecent … others are in much harder situations.”

But Satrapi is convinced that the protests over Amini’s death and the “Woman, Life, Freedom” slogan have paved the way for long-term change in Iran. “I never thought this regime would fall in a year,” she says. “I always knew that the regime would have the means and the capacity to destroy the movement one more time. But next time, or the one after, it’s going to be the end. You cannot have a society that is more than 85% against you, that is modern and wants equality, if you have a mentality from the middle ages – albeit with modern weapons – and expect to rule them for ever.

“Never forget, all the dictatorships are the same,” she adds. “A night before they fall, everyone says: they are so solid, it’s impossible they can fall. Then they fall, and everyone asks: how could they have held for so long?”

after newsletter promotion

For Satrapi, the book was about giving people an insight into “something huge that’s going on. Every single thing we are talking about: the war in Ukraine, Gaza, Houthis in the Red Sea – all of that is related to what is happening in Iran.” She feels Iran’s influence on geopolitics is like an octopus, with the west always grappling with its arms, “but actually they are just arms, the head is what is happening in Iran itself”.

She is adamant that her brief return to comic-book art will be only for this project. “This was a really special book, and that’s it,” she says. She will continue her film work and subject matter beyond Iran, always cautious to avoid pigeonholing. “When you are Iranian, what people expect from you is to talk about murder, mayhem, misery, veils and the atom bomb. If you’re an English director, do you always have to make films about the miners’ strike or the queen? No. You can also make comedy. Expecting us to stick to a certain subject is taking our humanity away from us … We’re not only suffering – we’re human, we like to laugh and think up surreal stories, too.”

The only thing that counts as an artist, she says, is freedom to do surprising work. You cannot repeat the same thing. “Otherwise I’d finish up like Jimi Hendrix, playing Hey Joe over and over again … ”

Creating Woman, Life, Freedom was about taking action through art. “At the start I was reposting on Instagram, which gave me the good conscience that I was doing something, but actually it was nothing,” she says. “The only thing I can do is cultural work … This book is a message to the Iranian people to say, listen, you are not alone.”

Male Turf:

Coco & Jean-Pierre Perrin

The Rich Kids of the Regime:

Patricia Bolanos & Farid Vahid

Rebelling at Twenty:

Paco Roca & Farid Vahid

The Art of Rebellion:

Deloupy & Farid Vahid

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion