For some years, Yorta Yorta man Jason Tamiru’s job was to help secure “thousands of bones, hundreds of people” from museums, institutions and private collectors around the world. As a cultural heritage officer for Indigenous nations in north-west Victoria, Tamiru would organise burial ceremonies and inter the remains back on Country. “It’s a duty, mate,” says the theatre director. “A role I took on with honour.”

The bones of children and babies “hit you right in the soul and the spirit”, he says. He vividly recalls the return of perhaps the most widely known Indigenous infant: the “Jaara baby”, originally buried in the hollow of a tree in the mid-19th century near the town of Charlton. Wrapped in possum skins, the baby was reportedly discovered in 1904 by an axeman felling timber. It wasn’t until almost a century later, in 2003, that the Melbourne Museum returned the remains to the Dja Dja Wurrung people.

“We put the baby back into a tree, back on Country, including all its belongings,” says Tamiru. The baby was wrapped in a new possum skin cloak and given a new rattle. Traditional tree burials are “very sacred” and reburying the bones of ancestors reconnects cultural lines by “absolutely awakening those spirits”, he says.

But the remains of thousands more ancestors are still being sought by Indigenous nations across Australia, despite the existence of a federally funded program for more than 30 years to repatriate them from collections in Australia and across the world. Their bodies ended up in universities, medical schools and in the hands of private collectors across the US, UK and Europe, but museums cannot be forced to return human remains. In Australia, more than 2,850 ancestors have been returned to custodianship of their communities, but the eight museums involved in the Indigenous repatriation program since 1990 still hold about 10,500 First Nations ancestral remains. The South Australian Museum alone collected the remains of about 4,600 mostly Indigenous people.

It is “heartbreaking” for First Nations people when their ancestors’ remains are withheld, says Tamiru, whose experiences in repatriation inform a new play, The Return, which Tamiru is directing at Melbourne’s Malthouse theatre as part of the Rising festival. “Institutions labelled us with letters and numbers and dehumanised us. When we connected with these places, we humanised the people they had in there.”

“It was a massive industry at the beginning of colonisation, snatching people we had laid to rest from their graves. This place was a goldmine for collectors and grave robbers. There was good money to be made from this business. A lot of people, especially those mad scientists, they believed we [Indigenous people] weren’t going to be here today, and they wanted to get as much information as they could. They were fascinated about who we are, where we come from, and they saw us as the missing link to history.”

When the Jaara baby was returned to the Dja Dja Wurrung for reburial in 2003, a former Melbourne Museum curator, the anthropologist Alan West, wrote a scathing memo in which he objected to the return of the remains when cataloguing was still incomplete: “The action is referred to as repatriation, but this term is really a smokescreen to hide the museum’s facilitation of unashamed vandalism,” he wrote. In 2006, the Victorian government mandated the Victorian Aboriginal Heritage Council as a statutory authority to oversee Indigenous cultural heritage, including strong legal protection for Aboriginal human remains within the state.

“It’s all about museums and us forming true relationships, so they can put connections to what they have,” says Tamiru. “Once people have that human connection, they become a bit softer, much more open in handing back. Some institutions are still living in the dark ages; they question who owns this information, they question who owns this piece of mankind. They don’t understand this is actually part of our family, and we need to get them back home.”

Tamiru approached playwright John Harvey, who is of Saibai Island (Torres Strait) and English descent, to write The Return. The pair first met years ago when Tamiru was producing Deadly Funny, a platform he created for Indigenous standup comedians. It wasn’t until years later that Harvey learned Tamiru had helped bring ancestral remains back home. “I thought, ‘Wow, that is massive’,” Harvey says. “I can’t imagine how tough that must be as an Indigenous man to work and walk in that space.”

Harvey says the greatest challenge in writing The Return, which takes place over two centuries and interweaves three narratives – a bone collector, a museum creator and a repatriation officer – was to make clear, as per Tamiru’s wishes, that this was not one person’s story but rather the story of many.

As he learned while researching, the emotional impact is deepened when you know that one body might be shared among anthropologists and anatomists in disparate institutions, using different filing systems. One ancestor’s bones might be scattered between Edinburgh and Washington, to meet the historical “thirst” of anthropologists and anatomists.

And even if the remains are found, or finally gathered together from across the world, “there’s a lot of deep research and resources that have to go into finding out the provenance of remains”, Harvey says. In January, the Australian government announced that it would build a new cultural precinct known as Ngurra – a word meaning home, belonging and place of inclusion – which will be dedicated to returned remains whose provenance is unknown and who therefore cannot be reburied on their own Country.

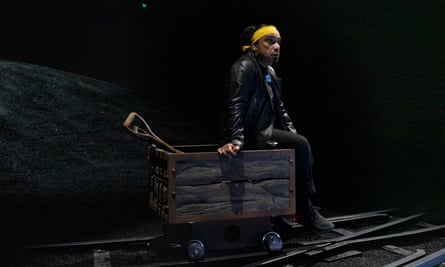

Indigenous actors, including Jimi Bani, Ghenoa Gela and Guy Simon, each play several roles in The Return, including non-Indigenous characters; Tamiru says he cast only First Nations actors to “challenge stereotypes” of who gets represented on stage. The western paternalistic idea of ownership of Indigenous bodies endures, says Tamiru, but he senses growing support from museums and politicians.

“People are starting to learn and understand and educate themselves about our history, about who we are in our identity,” he says. “Through that maturity they understand there is a history here, and a culture, and there are some ghosts in the history that are now awakened and need to be put to bed.”

The Return opens at the Malthouse’s Merlyn theatre on 18 May, in Melbourne. The Rising festival begins on 1 June.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion