Dialogue

Cannon, Williams, and Womanist Survival

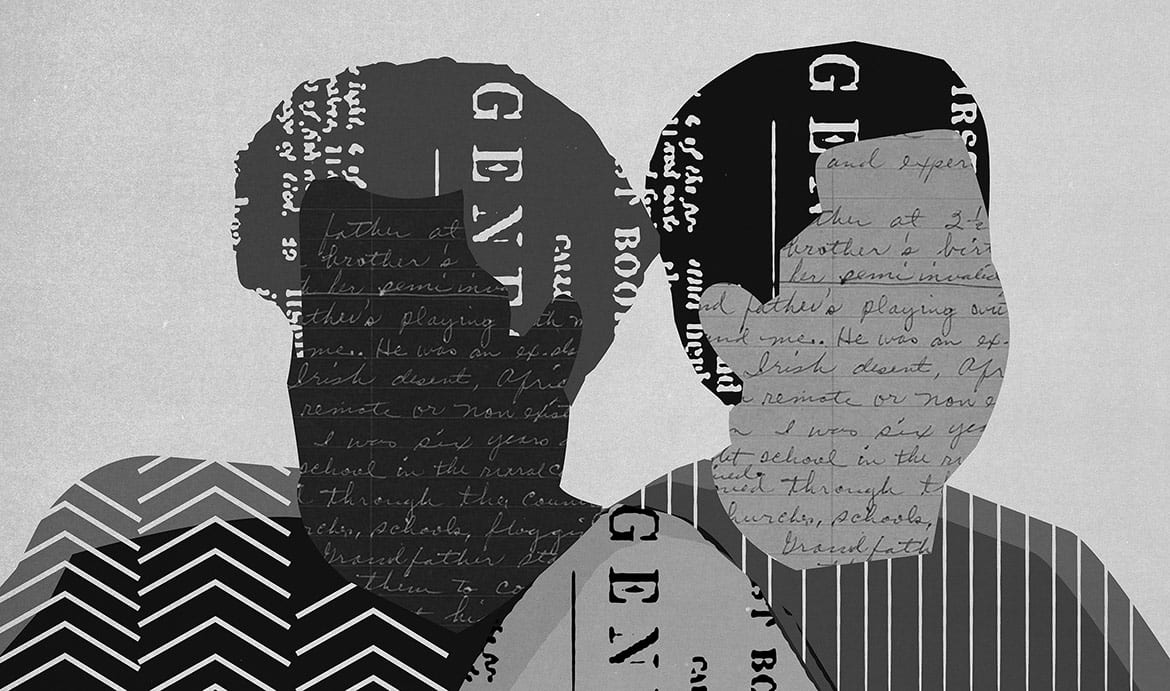

Illustration by Mark Harris

By Gary Dorrien

The womanist intervention in Black theology was coming for years before it yielded a critical mass of womanist and Black feminist theologians. I witnessed the incubation period in the 1970s when I was studying at Harvard Divinity School, Union Theological Seminary, and Princeton Theological Seminary. White women were entering theological education in large numbers then, but we had few Black female classmates. All the Black theologians we studied were male and all the female theologians were white, as a proverbial saying later put it; at Union the chasm was remarked upon.

Sometimes Black women pointed to the absence of people like themselves in Black theology. More often, others raised the issue in their presence, which was better than not raising it but was usually problematic. Our Black female classmates were often asked to declare whether their race or gender took higher priority for them. The womanist tradition they created refused to make an either/or answer. Womanists said they could not identify with the heroic male radicalism of Black liberation theology or the sisterhood-universalism of white feminist theology. If they were going to enter the theological academy and the ordained ministry, they had to theologize out of their own experiences as Black women who had survived multiple intersecting forms of denigration.

All four founders of womanist theology earned doctoral degrees at Union Thological Seminary in the 1980s or early 1990s— Jacquelyn Grant, Katie G. Cannon, Delores S. Williams, and Kelly Brown Douglas.1 Though they were too spread out from each other to have taken classes together, these womanist founders worked together and supported each other, defying the competitive ethos of the academy. They wrote about seeking wholeness in one’s life, being attuned to the God within, working for justice, and building peaceable communities that enable all people to flourish. Cannon, Williams, Douglas, and Emilie Townes identified womanism with the view that theologies of redemptive suffering are pernicious. If this contradicted Martin Luther King Jr., the Black liberation theology of James Cone, and most of the Black church tradition, most of the womanist founders were willing to say so. But womanists were not one-view-only on any subject, and nearly all womanists of the first and second generations were committed to the church.

Katie G. Cannon grew up in Kannapolis, North Carolina, near Charlotte. Her father was a truck driver; her mother worked as a domestic; for college she went to Barber-Scotia College; and for seminary she went to Johnson C. Smith in Atlanta. She was a legendarily buoyant and expressive teller of her story, which I heard many times. There were different versions, depending on the audience and occasion. To womanist gatherings, Cannon embraced her role as the mother of womanist ethics. To church groups she aimed at the next generation coming up. To my doctoral students she once urged that no job is worth feeling depressed or put upon. If it turns out that being an academic doesn’t bring you joy, please find another line of work; we don’t need even more desultory professors!

Her class at Johnson C. Smith had four women, a first for the seminary. All were single, in their early 20s. At first, the seminary housed the women in guest rooms in a male dormitory, not knowing what else to do with them. Then they were moved into trailers behind the married-student apartments. One-third of the seminarians were Vietnam veterans, one-third were trying to avoid being sent to Vietnam, and it felt to Cannon that the other one-third had been raised all their lives to be ministers. Hardly anyone supported the women for being there. Even Christian Education directors were supposed to be male. Cannon majored in Hebrew scripture, which took her to Israel, where she was verbally accosted by racists who told her to go home. She had never been called the n-word until she got to Israel. There she heard it many times. Cannon was stunned and gasping, driven to the wilderness. Years later, telling this story, she would say, “You know, in a situation like that, you hold onto God for dear life.”

In seminary, Cannon held onto God through the Hebrew Bible. In 1974 she enrolled at Union to get a PhD in it, not realizing that Hebrew Bible was the most old-school of Union’s doctoral fields. Union Seminary felt unapproachably elitist to her—the professors and the students. In certain contexts, telling this story, Cannon would say, “I had no understanding of white culture or educational culture. None. None. None. Students from Bangladesh were more acculturated than I was.” She was a stranger who didn’t belong. The white world was alien to her, and white academic culture felt impossibly alien. This section of her story would run long or short depending on the audience. Cannon knew what it meant to students when she opened up on this subject, but she would cut it short if she spotted professors she didn’t know. In 2005 and 2006, Union president Joe Hough and I asked her to join the Union faculty. The first time she said that teaching at the other Union Theological Seminary, in Richmond, Virginia, kept her close enough to her family. The second time she added, “Gary, my wounds from Union are deep.”

The wounds were deepest from her first year, when she had no friends and no one in Hebrew Bible would take her as an advisee. Two hang-in-there decisions kept Cannon at Union long enough for womanism to bloom. Roger Shinn and Beverly Harrison invited her to join them in Christian ethics, and Cannon reluctantly said, well, OK. She had no interest in ethics and grieved at giving up her dream. At the same time, she made an appointment with her roommate’s therapist, a white female psychologist on Third Avenue, who told Cannon she had to learn how to engage the white world in a way that made it tolerable. When Cannon got to this part she would nearly always say, “I had to make sense of this big ball of whiteness that was scaring the hell out of me.” Cannon was surprised that the therapist’s emphasis on individual freedom and equal rights for women made some kind of sense. She befriended a few white feminists at Union and shuddered at finding her community of support among them. Cannon was learning to live with the pain, trauma, irony, and contradictions of her past and present, which she would soon call womanist survival.

Beverly Harrison urged Cannon to write from her own experience, but Cannon couldn’t trust Harrison. She wrote a paper sprinkled with quotes from Kierkegaard and Wittgenstein. Harrison wrote back: please stop with the Kierkegaard and Wittgenstein business. The same thing happened on a subsequent paper, this time adorned with quotes from Niebuhr and Tillich. Harrison grew emphatic; we already know about Niebuhr and Tillich. When Cannon told this story to students, she accentuated Harrison’s phrase, “we got that already.” Harrison said the academy doesn’t know what you know. Cannon was incredulous—did Harrison really want her to write about Black women in Kannapolis? Harrison said, yes, the oral tradition you’ve heard all your life, that’s what social ethics and the academy need. Cannon fretted that this white woman must be out to destroy her. Who would give her a PhD for writing about the sayings of her mother and grandmother?

Alice Walker was already writing womanist prose before she coined the term womanism in 1979. Walker drew attention to a mostly forgotten Black novelist of the 1930s, Zora Neale Hurston. In 1982 Walker published The Color Purple, a cultural landmark that sang and soared through Celie’s luminous folk voice. The following year, Walker famously wrote that a womanist is a Black feminist or feminist of color who is always in charge, often considered to be willful, loves other women, is committed to survival and the wholeness of people, and loves herself. Walker named the ethic and sensibility by which many Black women entering the theological academy named themselves, supported each other, and marked their nonidentification with existing theological perspectives. Cannon read herself into social ethics through Walker and Hurston. Walker was a spiritual humanist and Hurston looked down on religion, but they opened a gold mine of riches for Cannon and many others.

Carter Heyward was a classmate of Cannon’s at Union and later her faculty colleague at the Episcopal Divinity School. In 1982 Cannon told Heyward she felt compelled to complete her doctorate to repay the Black women who nurtured her and were counting on her. She said it tormented her to realize how little was written about Black women and their wisdom. She was patching together what little she could find. For five weekends she met with seven feminist theologians called together by Heyward and calling themselves the Mud Flower Collective. The others were Harrison, Delores Williams, Mary Pellauer, Ada María Isasi-Díaz, Nancy Richardson, and one more who dropped out at book time. They vowed to trust each other enough to have difficult, painful, honest discussions worth having. There had to be a level playing field, even though Harrison was a major figure in social ethics and half the group had dissertations to complete. They succeeded, trusting each other enough to bruise each other’s feelings and to pioneer a model of dialogical feminist theology. Harrison later recalled that the Mud Flower group helped her work through the paralyzing guilt about racism that thwarted her from breaking its power over her.

The discussions produced a book titled God’s Fierce Whimsy. For many years Cannon met people at conferences who told her they admired the book and were helped by it. Yet aside from Christianity and Crisis, a magazine closely connected to Union, the book received exactly two reviews. The Jesuit magazine America ran a polite notice, the journal Lesbian Contradictions ran an actual review, and that was it. Cannon was shocked. It was her first experience of a possibility she had not previously considered, which later played a role in her lecture circuit story: What if you make an important intervention and they just ignore you?

She graduated from Union in 1983, joined the faculty at EDS, self-identified as a womanist for the first time in 1985, and published the book version of her dissertation in 1988, Black Womanist Ethics. White Americans, she wrote, prize self-reliance, frugality, and industry, virtues that facilitate their success. White theologians describe a self with a wide capacity for moral agency, taking for granted that each person is free and self-determining, which underwrites the white Christian idea that voluntary suffering is an exemplary moral norm. Cannon said none of this applies to Black Americans, especially to Black women. To internalize white values is to legitimate the power that whites hold over Blacks, thereby worsening the cycle of humiliation. In racist America, she wrote, the game is rigged against African Americans who try to climb a career ladder. Even when they adopt white individualism and frugality, they are put down anyway. Moreover, suffering is not a choice or a desirable norm for African Americans, especially for Black women. Suffering is a repugnant everyday reality to overcome.

Literary scholar Mary Burgher wrote that Black women writers turned their lost innocence into “invisible dignity,” sustained a “quiet grace” despite being refused the possibility of feminine delicacy, and converted their unchosen responsibilities into “unshouted courage.”2 Cannon said that perfectly describes the virtues of womanist spirituality. Hurston portrayed virtue as a robust, self-respecting, feisty affirmation of one’s life and of life itself. She was long on “unctuousness,” one of Walker’s favorite words—the virtue of taking the good and bad together in stride.

Cannon conceived womanist ethics as a corrective enterprise that works within and outside the guild, interpreting traditional paradigms from the perspectives of previously excluded Black female subjects.

Cannon conceived womanist ethics as a corrective enterprise that works within and outside the guild, interpreting traditional paradigms from the perspectives of previously excluded Black female subjects. As a critical enterprise, it points to the silencing and denigration of Black women, including the sexist content of Black male preaching. As a constructive enterprise, it describes the genius of Black women in creatively shaping their destinies. Cannon defended womanism valiantly from what she called “golden-boy mind-guards in professional learned societies.” In her chapter in the showcase forum, Stacey M. Floyd-Thomas’s reader Deeper Shades of Purple (2006), Cannon said the academy was structured to ignore and demean womanist scholarship:

From 1983 until now, storms of opposition, bigotry, and suspicion mount. . . . Womanist projects in our various disciplines of study are punctuated with utter silence in the sacred halls of the majority of the accredited colleges, universities, and seminaries. . . . Far too many of our professional colleagues, who are defenders of androcentric, heteropatriarchal, malestream, white supremacist culture, experience our very presence as colleagues as a cruel joke.3

This same academy somehow believed it had surpassed womanist scholarship about blackness and Black female identity. Townes, Douglas, and a few other womanists half-welcomed the French deconstructionist tide that swept the US American academy in the 1990s. Cannon was much more dubious of it for deriding identity concepts and the appeal to personal experience. She said there are far worse things to oppose than essentializing a racial or gender identity. Womanism was born in the refusal of Black women to choose between their racial and gender identities. Being Black and female were profoundly and equally important to her. She felt she had barely withstood one form of being marginalized only to be pushed aside by the next academic fashion. Cannon said if younger Black women favored hip-hop, hybrid identities, and poststructuralist jargon, she would not tell them they had a moral obligation to be womanists. Womanism is a self-naming sensibility, she would say, but please don’t call yourselves post-womanists, a term that repulsed her. What matters is to actualize the definition of womanism, not to show up those who came before you.

Whenever she got rolling on this point, Cannon would say that the idea of building on the wisdom of ordinary Black women cannot be wrong or outdated. She was a legendary teacher who strove to make every voice in the classroom heard, encouraging students to “fill the container” with whatever they brought to the course. Cannon was not there to penalize them with a bad grade for something they did not learn. That approach had never worked for her and she didn’t believe in it, no matter how many colleagues and deans admonished her to hand out some C grades. To the end of her days, Cannon told stories of being chided on this subject at every place she ever taught. She disliked the anxiously radical, white, sometimes toxic culture of EDS. She was much happier when she moved to Temple University in 1992, where she mentored Stacey Floyd-Thomas and Angela Sims as doctoral students. From 2001 until her death in 2018, Cannon taught at Union Theological Seminary in Richmond, which changed its name in 2010 to Union Presbyterian Seminary.

At womanist gatherings, buoyant-Cannon took over, spreading cheer, welcoming newcomers, teasing old-timers, being the founder-mother, and urging one and all: “You have to do the work that your soul requires.” This deep-down conviction was her mainstay and maxim. Cannon never tired of saying that the call to teach was like a fire in her bones. To her, womanism was a way of knowing; the classroom was the ideal place to investigate what sustains life and wholeness. She was all in, giving the best she had, remembering where and how she entered, owning what her constellation of particularities made her, and expecting no less of everyone else.

Of the original womanist thinkers, Delores Williams is the most influential, partly because she accentuated her negations. Williams and her husband, Robert C. Williams, raised four children while he taught religion and philosophy successively at Central State University, Oberlin College, Wagner College, Vassar College, Fisk University, and Vanderbilt University, later serving as academic vice-president at Muhlenberg College. Robert Williams was teaching at Vanderbilt in 1977 when Delores Williams began her doctoral program at Union. In 1987 he died of a heart attack at the age of 51. Delores Williams is an extremely private person, a reticence I shall respect in this discussion. The void that her husband left upon dying so suddenly must have been searing for her. In 1990 she graduated with a dissertation titled, “A Study of the Analogous Relation between African-American Women’s Experience and Hagar’s Experience.” Three years later the book version, immediately a landmark in the field, bore a perfect gem of a title, Sisters in the Wilderness, and was replete with a stunning cover photo of three young head-scarfed Black women.

Williams was a magnet for Union students long before she joined the Union faculty. She didn’t sound like any other Union professor but like the archetypal strong, overcoming, keep-it-real womanist mother. Her first advisor was Cone, but they did not get along and she switched to theologian Tom Driver. In the late 1980s, while writing her dissertation and teaching at Fisk University, Williams told stories about being asked to explain feminism to groups of Black Christian women. One woman told her that feminism was like a size-five dress in a fancy store. It looked pretty in the window, “but there just ain’t enough in it to fit me.” Another observed that every victory for feminism in US American history reinforced white supremacy, so how was the pro-feminist Williams not an advocate of white supremacy? Williams replied that she wanted to believe that the new feminism was better than the old one, but she couldn’t pretend to actually believe it: “The failure of white feminists to emphasize the substantial difference between their patriarchally-derived-privileged-oppression and black women’s demonically-derived-annihilistic-oppression renders black women invisible in feminist thought and action.”4

That was a foretaste of Sisters in the Wilderness. Williams said she drew strength from watching Black women hold together their families and churches. But it grieved her that many Black women were colonized by the Black churches they loved. Even Black liberation theology shackled Black women. Liberation theologians, Williams acknowledged, have one strand of the Bible that supports their position—God delivering the Hebrew slaves from bondage in Egypt and Jesus describing himself as the liberator of the poor and oppressed. But Williams pointed to a second tradition of Black American biblical appropriation that emphasizes female activity, plays down male authority, and revolves around Hagar—a female slave of African descent forced to be a surrogate mother. She detailed the parallels between the Hagar story and the story of African American women. Black women were abused by white men, raped by white men, and forced by white men to serve as sexual surrogates for white women, much like Hagar. Williams said the Hagar-centered tradition of biblical appropriation cannot be called liberationist or any part of a liberation hermeneutic. Hagar fled from slavery and God tracked her down in the wilderness, telling her to return to Sarah and slavery. God helped Hagar and her son Ishmael survive her doomed escape to freedom. Later in the story, God helped Hagar and Ishmael figure out how to survive their banishment from the home of Abraham and Sarah. Certainly, Williams observed, the Hagar story shows God helping Hagar to survive and to achieve a minimal quality of life by her initiative. But it has nothing to do with liberation.

Williams stressed that taking seriously the Hagar tradition precludes any claim that God always works to liberate the oppressed. In the Bible, slavery is a taken-for-granted feature of ancient society, except when Hebrews are enslaved. Williams admonished that Cone and other liberationists worked with only one strand of the Bible, looking past the fates of the oppressed in it.

Liberation theology, she argued, does not work for Black women. It does not fit them and it leaves them out, rendering them invisible. Williams did not say that liberation theologians should stop appealing to Moses and Luke 4. She said they need a second hermeneutical lens that makes visible the victims screened out by liberation theology. It is a womanist hermeneutic of “identification-ascertainment” operating in three modes—subjective, communal, and objective. In the subjective mode, the theologian analyzes her own faith journey to discover with which biblical figures and elements she identifies. In the communal mode, the theologian analyzes the faith journey of her religious community, looking for the biases in church sermons, songs, testimonies, and rituals. In the objective mode, the theologian gathers the yield of her research, drawing a conclusion based on the evidence.

Williams charged that Black liberation theology shared with Black denominational churches a tendency to overuse a self-serving approach to the Bible. The exodus from Egypt is a holistic story with liberating elements and the extermination of the Canaanites and the taking of their land. Liberation theologians needed to linger over God’s sanctioned genocide in the promised land of Canaan. It cannot be, Williams said, that Black theology should fix on the same texts and tropes that worked during the abolitionist period. If Black religious experience has not changed since the Civil War, the implications are disastrous for Black women.

If racial oppression created the Black experience, and blackness is a qualitative, symbolic, and (in some renderings) sacred aspect of it, what are the active constituents of the Black experience? Williams discerned four answers in the regnant Black theologies. The horizontal encounter is the interaction between Blacks and whites that yields Black suffering. The vertical encounter is the meeting between God and oppressed people that sustains hope and meaning. Transformations of consciousness are positive when they enhance the collective self-worth of oppressed people and negative when oppressed people lose hope and identity. An epistemological process of processing data and determining modes of action takes place in all three of these categories. Cone conceived the horizontal encounter as unremittingly hostile to Blacks, emphasized the church’s vertical encounter with God in relation to God’s liberating activity in the world, and touted liberationist consciousness as a way of knowing. J. Deotis Roberts conceived the horizontal encounter as both negative and positive, agreed with Cone that the vertical encounter is the most salient feature of the Black experience, contended that Black experience is affected by certain transformations of consciousness, and described reconciliation as intrinsic to the gospel.

Williams called for a Black theology that pays attention to the “re/production history” of Black women. The survival strategies of Black women created modes of resistance, sustenance, and uplift that saved and enabled entire Black communities.

Williams countered that Cone and Roberts were more alike than not, both employing the androcentric language of struggle that suffuses Black art, religion, and culture, yielding the masculine concepts of personality and victimization that pervade Black liberation theology. Williams called for a Black theology that pays attention to the “re/production history” of Black women. The survival strategies of Black women created modes of resistance, sustenance, and uplift that saved and enabled entire Black communities. The re/productive history is the context in which Black women and Black men together survive the wilderness experience. Williams argued that the contrasts between liberation theology and womanist theology run across the spectrum of categories. In liberation theology, the horizontal encounter features Black males facing off against white males. In the womanist wilderness, horizontal encounters are mostly female-male and female-female. In liberation theology, Black people suffer almost entirely at the hands of whites. In the womanist wilderness, there is no evading the suffering that Black women experience in their families. In liberationist renderings of the encounter with God, God confers divine sanction on sexist gender roles, moral norms, and cultural forms. In the womanist encounter with God in the wilderness, women are empowered to persevere in spite of trouble and to find a way where no way is apparent.

Williams argued that atonement theology and preaching harm Black women. The image of a surrogate God, she said, does not hold saving power for Black women; instead, it reinforces the very exploitation that Black women have experienced as surrogates. She ran through the classic atonement theories and rejected all of them. If Jesus is saving for Black women, it cannot be as a surrogate or an example of sacrificial love. Jesus is saving to Black women only because he resisted being victimized, providing a model of resistance for oppressed people.

Jesus came to show people how to live, not to be crucified for their sake. Nothing in the cross, Williams said, is redeeming; it is an image of defilement. The same God who did not will the condemnation of Black women to surrogate slavery did not will the execution of Jesus. Williams reasoned that the redemptive vision of Jesus was ministerial, devoted to righting the relations between body, mind, and spirit on individual and communal levels. Jesus cast out demons, performed healings, called people to wholeness, and raised the dead. He conquered sin when he was tempted in the wilderness, not when imperial power tortured him to death on a cross. The ministerial life of Jesus and his resurrection are what is saving in Christianity. Williams urged Black churchwomen to confront their exploitation, including the roles that the cross-theology of suffering contributed to it.

Driver retired from Union in 1991 and Williams took his position, an appointment weighted with historic significance. She and Harrison co-taught the course “Emergent Issues in Feminist and Womanist Theologies,” assigning chapters of what became Sisters in the Wilderness. Shortly after the book was published in 1993, Williams played a featured role at a storied liberal Christian conference in November 1993 in Minneapolis titled, “Reimagining: A Global Theological Conference by Women; for Men and Women.” Over two thousand participants crowded into the Minneapolis Convention Center. Many speakers said quotable things that shocked readers of denominational magazines, but Williams was by far the most quoted speaker. She told the conference that Black Americans were well acquainted with the imperative of reimagining Jesus. The white Jesus who condoned slavery and racism could not be a savior to Black people. Williams rehearsed her signature argument that Jesus conquered sin in the wilderness, not on the cross. In the post-lecture discussion, someone asked how atonement doctrine should be reimagined. What is the good theory of atonement that the church should teach? She said there is no such thing: “I don’t think we need folks hanging on crosses, and blood dripping, and weird stuff. We need the sustenance, the faith, the candles to light.”

The conference set off a furor against the sponsors and speakers that raged for months. Afterward, when Williams spoke to church groups, she knew her reputation preceded her. She wanted to be known for the painstaking argument she made in Sisters in the Wilderness for a second hermeneutic, not for an offhand remark that sounded flippant out of context. It was a cruel irony for someone so intensely private. As usual, her friends were never quite sure how much it bothered her. Williams kept her feelings to herself, concentrating on her classroom teaching.

Her public life revolved around Union students, who loved her. They crowded into her classes, laughing when she said that teaching at Union was not a bad job, but if she ever hit the lottery, she would resign instantly. Second-generation womanists JoAnne Terrell and Marcia Riggs lauded Williams as a “womanist’s womanist.” Linda Thomas, whom Williams taught as a teaching assistant from 1979 to 1981, said Williams made it possible for her to become a professor by showing her how to be a womanist professor. Lakisha NyHemia Williams, representing the last generation that Williams taught at Union, said she was “the bridge that carried us over,” partly because she was “among the bravest of us.”

Williams retired in 2004 and returned to Louisville. Though students pleaded with her to hang on a bit longer, she was done with Union and told friends she would answer no more calls from the institution after she left. At Union she had become the symbol of the womanist alternative to liberation theology, the one who epitomized womanism in thought and style. Sisters in the Wilderness had a movement spirit, a realigning argument, an ambitious reach, and a perfect title. It brilliantly called for theologies that spotlighted the invisible women, Canaanites, Native Americans, Palestinians, and lesbian-gay-bisexual-transgender-queer persons obscured in canonical liberation theology. Today, many students who come to Union to learn about womanism know only about Williams when they arrive. To them, womanism is the interpretive theological argument that she expounded. Above all, as Lakisha Williams registered, Williams is a symbol of bravery. After she retired, much of the graduate school traffic moved from theology to religious studies, often combined with African/African American studies. Many who take this route consider Williams to be their forerunner.

Many in this latter group let go of Hagar and the Bible, too, reclaiming only the sources within African and African American experience that value the thriving of Black women—in literature, poetry, speeches, stories, spirituals, blues, R&B, rap, hip-hop, jazz, African oracles, and art. Some count Williams as their last stop out of theology. But Williams was emphatically a theologian who wanted Black women to convert the Black churches to womanist theology. She inspired many Black women to enter the ministry with this aim. However well and good it may be to influence the Religious Studies Department, the womanist founders aimed much higher by aiming to change the Black Church.

Notes:

- Union Theological Seminary was a major contributor to the revival of Protestant theology in the 1930s and 1940s through the work of such distinguished faculty as Paul Tillich and Reinhold Niebuhr. It also played an important role in the ecumenical movement and the development of neo-orthodoxy. James H. Cone, considered to be the founder of Black liberation theology, began his long tenure at Union in 1969, and womanist theology was birthed among Union doctoral students in the mid- to late 1980s.

- Mary Burgher, “Images of Self and Race in the Autobiographies of Black Women,” in Sturdy Black Bridges, ed. Roseann Bell et al. (Anchor, 1979), 113.

- Katie G. Cannon, “Structured Academic Amnesia,” in Deeper Shades of Purple, ed. Stacey M. Floyd-Thomas (New York University Press, 2006), 22, 23.

- Delores S. Williams, “The Color of Feminism: Or Speaking the Black Woman’s Tongue,” Journal of Religious Thought 43, no. 1 (1986): 42–58.

Gary Dorrien teaches at Union Theological Seminary and Columbia University. His many books include his first volume on the Black social gospel tradition, The New Abolition, which won the Grawemeyer Award; and his second volume, Breaking White Supremacy, which won the American Library Association Award. This article is based on volume three, A Darkly Radiant Vision, to be published in 2023 by Yale University Press.

Please follow our Commentary Guidelines when engaging in discussion on this site.