Spirituality

Is the “God Spot” Rooted Far Below Our Brain’s Thinking Cap?

Spirituality and religiosity may be tied to circuits rooted in the brainstem.

Posted July 3, 2021 Reviewed by Vanessa Lancaster

Key points

- For decades, there's been an ongoing debate about whether or not spirituality and religiosity are tied to a specific "God Spot" in the brain.

- In 2012, a neurotheology-based study concluded that "spiritual experiences are likely associated with different parts of the brain."

- New research (2021) suggests that the brain's "God Spot" may be rooted in neural circuits tied to the periaqueductal gray area of the brainstem.

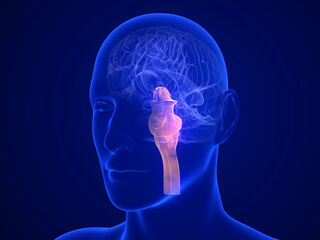

According to a new study, spirituality and religiosity may be tied to neural circuits within the periaqueductal gray (PAG) region of the brainstem (Ferguson et al., 2021).

"Our results suggest that spirituality and religiosity are rooted in fundamental, neurobiological dynamics and deeply woven into our neuro-fabric," stated first author Michael Ferguson in a July 1 news release. "We were astonished to find that this brain circuit for spirituality is centered in one of the most evolutionarily preserved structures in the brain."

Ferguson et al. used a technique called "lesion network mapping" to investigate whether or not they could pinpoint a neural circuit for spirituality and religiosity in 193 patients with brain lesions. This technique was applied to two different brain lesion datasets (N1 = 88; N2 = 105) "to test whether lesion locations associated with spiritual and religious belief map to a specific human brain circuit."

"We found that brain lesions associated with self-reported spirituality map to a brain circuit centered on the periaqueductal gray," the authors explain in their abstract. "Intersection of lesion locations with this same circuit aligned with self-reported religiosity in an independent dataset, as well as prior reports of lesions associated with hyper-religiosity."

Based on these findings, Ferguson et al. conclude: "[Our] findings suggest that spirituality and religiosity map to a common brain circuit centered on the periaqueductal gray, a brainstem region previously implicated in fear conditioning, pain modulation, and altruistic behavior."

Hyper-Religiosity or Lack of Spirituality Map to Different PAG Nodes

The first dataset included 88 neurosurgical patients who underwent brain surgery to remove lesions widely distributed throughout the brain. They also answered questions about "spiritual acceptance" before and after surgery.

The second dataset included 105 combat veterans with lesions related to traumatic brain injury from the Vietnam War. These patients responded to surveys with questions about their religiosity (e.g., "Do you consider yourself a religious person? Yes or No?").

Using lesion network mapping, the BWH team found that self-reported spirituality or religiosity mapped directly to specific brain circuits centered on the PAG. Interestingly, this PAG circuit includes "positive" and "negative" nodes. Almost like an "on/off" switch, brain lesions that disrupted specific nodes appeared to increase or decrease self-reported religious and spiritual beliefs.

A review of existing literature by the researchers also unearthed "several case reports of patients who became hyper-religious after experiencing brain lesions that affected the negative nodes of the [PAG] circuit." Conversely, legions that disrupted other nodes in the PAG region of the brainstem appeared to decrease spirituality and religiosity.

Does a Single, Localized "God Spot" Exist in the Human Brain? Probably Not.

A previous study (Johnstone et al., 2012) of brain injury patients by researchers at the University of Missouri-Columbia was able to replicate earlier studies from that era suggesting "that a frontal-parietal circuit is related to spiritual-religious experiences." The authors also speculated that a "decreased focus on the self (i.e., selflessness), associated with decreased right parietal lobe (RPL) functioning, serves as the primary neuropsychological foundation for spiritual transcendence."

About a decade ago, Johnstone et al. wrote: "Increased frontal lobe functioning also appears to be related to more frequent religious practices (and spiritual experiences to a lesser extent)." However, they also noted that "the specific neuropsychological process/mechanism [of spiritual transcendence] remains uncertain."

"We have found a neuropsychological basis for spirituality, but it's not isolated to one specific area of the brain," first author Brick Johnstone said in an April 2012 news release. "Spirituality is a much more dynamic concept that uses many parts of the brain. Certain parts of the brain play more predominant roles, but they all work together to facilitate individuals' spiritual experiences."

In an August 2012 Psychology Today blog post, Nigel Barber reported on this study. He concluded that "spiritual experiences use many different parts of the brain: the God spot is functional rather than anatomical."

The "God Spot" May Have Functional Roots Connected to Our Reptilian Brain

Accumulating evidence suggests that the functional connectivity between cortical regions in the cerebrum and subcortical regions located beneath the cerebral cortex plays a previously underestimated role in whole-brain cognition. (See, "My Decades-Long Quest to Decode a Quirky 'Super 8' Brain Map.")

Based on my ongoing interest in cerebral and non-cerebral functional connectivity, a fascinating aspect of the latest (2021) research into spirituality and religiosity from Harvard Medical School is the possibility that hyper-religious beliefs or a lack of spirituality may be tied to specific neural circuits rooted in subcortical "non-thinking" parts of our reptilian brain. Of course, much more research is needed to understand better how all of these neural networks are interconnected.

In the recent BWH news release, Ferguson cautions against "over-interpreting" his team's findings and notes that both datasets used for their analysis didn't provide much information about different patient's childhood and upbringing, influencing spirituality and religiosity in adulthood.

Additionally, both datasets only included patients from predominantly Christian cultures. Moving forward, in an attempt to better understand the generalizability of their latest results, the Brigham researchers acknowledge that they "would need to replicate their study across many backgrounds."

Soon, Ferguson also wants to investigate if their recent findings related to neural circuits in the PAG being linked to spirituality and religiosity might have clinical applications.

"Only recently have medicine and spirituality been fractionated from one another. There seems to be this perennial union between healing and spirituality across cultures and civilizations," Ferguson concluded. "I'm interested in the degree to which our understanding of brain circuits could help craft scientifically grounded, clinically-translatable questions about how healing and spirituality can co-inform each other."

References

Michael A. Ferguson, Frederic L.W.V.J. Schaper, Alexander Cohen, Shan Siddiqi, Sarah M. Merrill, Jared A. Nielsen, Jordan Grafman, Cosimo Urgesi, Franco Fabbro, Michael D. Fox. "A Neural Circuit for Spirituality and Religiosity Derived from Patients with Brain Lesions." Biological Psychiatry (First published: June 29, 2021) DOI: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2021.06.016

Brick Johnstone, Angela Bodlinga, Dan Cohenb, Shawn E. Christc & Andrew Wegrzync. Right Parietal Lobe-Related “Selflessness” as the Neuropsychological Basis of Spiritual Transcendence." International Journal of the Psychology of Religion (First published: April 18, 2012) DOI: 10.1080/10508619.2012.657524