Isaac, thank you for taking the time to talk with me today. It’s so good to get to learn from you, especially at an exciting moment in your scholarly life.

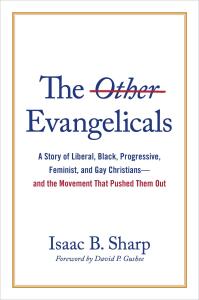

Your new book The Other Evangelicals: A Story of Liberal, Black, Progressive, Feminist and Gay Christians—and the Movement that Pushed them Out is coming out with Eerdman’s Press this Spring. Why did you decide to write this book?

Thanks for interviewing me! After working on this project for many years now, this is the first chance I’ve had to talk about it publicly and I appreciate the interest.

So, the book is based in part on my dissertation, which involved a much longer exploration of various kinds of evangelicals that have been largely overlooked in many of the standard pictures of twentieth century evangelicalism. I decided to write the book because I think there are a lot of people out there who will be interested in the stories I’m telling. I decided to write the dissertation for a lot of reasons! One reason is because I was convinced that U.S. American evangelicalism is a more complex phenomenon than many scholars and public commentators alike often acknowledge. Another reason was the discovery that there were a lot of fascinating, surprising, and untold or woefully under-told stories in evangelical history—stories that I felt could help shed light on the evolution of what it means to be evangelical in the contemporary U.S. context.

Yes, it’s a more diverse category than we are used to thinking of it as. What is the main argument then of The Other Evangelicals?

The main argument goes something like this: most standard accounts focus primarily on the emergence and rise to predominance of an interdenominational evangelical movement associated with an extensive sub-culture of flagship institutions, parachurch organizations, individual churches, and/or entire denominations. The standard version of the story usually (and rightly!) emphasizes the outsized influence of powerful evangelical figureheads like Billy Graham and Carl Henry, as well as bellwether institutions like Christianity Today, Fuller Seminary, and the National Association of Evangelicals. The usual story is a true story. This version of evangelicalism really did become the mainstream version. Over time, it also became increasingly known for its theological, social, and political conservatism, as well as its ideological and cultural homogeneity. But conventional versions of the story simultaneously tend to overlook the question of how it is that the mainstream version became mainstream.

This mainstream version of evangelicalism, the prevailing vision of what it means to be an official, capital-E evangelical, was shaped over time by a series of powerful leaders and largely self-appointed gatekeepers who policed the boundaries of evangelical identity, shaping it in their own image along the way. One of the most effective ways they did so, I argue, was by marginalizing divergent views and/or excommunicating dissenters who they believed were not evangelical enough. Another way of saying it might be that the usual story is about the “winners.” I argue that the “losers”—those who didn’t quite fit the mold for one reason or another—tell us as much about how mainstream evangelicalism became what it did as the winners.

That’s fascinating. So much of it is about power, isn’t it? But many of the arguments are theological in nature, right? I’m thinking here of the conflict between fundamentalists and modernists raging on in the post WWII era. Why has that real battle for the mantle of evangelicalism been so forgotten, do you think?

Oh that’s a great question! I think the answer depends in part on which battle you mean, because there were—and still are!—a variety of internecine struggles over who gets to claim the evangelical mantle. When it comes to the fundamentalist-modernist struggle over the evangelical name, which indeed lasted much longer than it often seems, I think one of the main reasons it has been forgotten is that, in the end, the “modernists” or “liberals” ultimately gave up. The fundamentalists and their heirs staked a decisive claim on the evangelical name, fought hard for their right to do so, and kept defending the territory on precisely those terms. Over time, the liberals and modernists arguably lost interest in the label and stopped challenging fundamentalism’s descendants for the right to claim it. A related reason, I think, is that historians of evangelicalism have often seemingly decided that the early twentieth century fundamentalists were legitimate representatives of the “historic evangelical tradition” and that modernists/liberals were not—that the fundamentalists were the “real” evangelicals.

Your book analyzes several groups of “Other” evangelicals in its chapters: Liberal, Black, Progressive, Feminist and Gay Christians. Why did you decide to structure it that way? And how did you handle overlapping identities?

Another great question—one that I occasionally struggled with during the research and writing in fact. Some of the structure was based on divisions that were more straightforward and self-evident. For instance, many if not most of the figures that I profiled in the Black evangelicals chapter or the Feminist evangelicals chapter were involved with particular organizations—like the National Black Evangelical Association (NBEA) or Evangelical Women’s Caucus (EWC)—that were significant factors in intra-evangelical struggles over evangelical identity. In other cases, there were figures who could have appeared in a few different chapters. Some were involved in multiple struggles, others were most closely affiliated with one specific movement, but in most cases, the decision ultimately came down to organizing the chapters and the figures profiled therein around specific arguments about what it means to be evangelical.

In developing what that meant, why did these groups have to be pushed out? Are there no possibilities for these groups to coexist within evangelicalism?

In almost every case, they never really were pushed out—at least not completely. In many sectors of the contemporary evangelical world, it is entirely possible to find folks who still identify, for instance, as progressive or feminist, and Black evangelicals and LGBTQIA evangelicals absolutely still exist of course. It’s the coexistence piece that I’d emphasize. Even though any number of these “kinds” of evangelicals still coexist within evangelicalism, I suspect that many contemporary evangelicals who might fit into one or more of these groups would likely admit that in some way, shape, or form they have often been made to feel like they are the only one. That’s by design. The powerbrokers in previous (and current) evangelical generations worked hard to marginalize feminist ideas, for one example, so that an evangelical who believes in the full equality of women in the year 2023 might not even know about books making feminist arguments from an explicitly evangelical perspective that were published decades ago.

Hmm, I imagine some readers might find that surprising. What surprised you in researching and writing this book?

One of the most surprising pieces of the puzzle was just how perennial certain kinds of arguments have been in the last century or so of evangelical history. Contemporary evangelicals are currently embroiled in a few different debates over the nature and limits of evangelical identity. But many of those very same controversies—over evangelicalism and race, over the role and place of evangelical women, over evangelical politics—have appeared countless times before. It really was stunning to see how certain arguments over the degree to which “real” evangelicals can reach divergent interpretations on any number of issues have cropped up time and again. It’s almost as though fiercely disagreeing over what it means to be evangelical has become one of the most determinative aspects of evangelical identity!

Wow, yes. And that seems to also be why taking a historical lens regarding these questions is so important. Writing a work of history like this is a major feat in and of itself. I’m curious–knowing that books can take on unexpected lives of their own– is there a response you’re hoping for, from evangelicals or others? What would you like folks to take away from your work?

I hope that there will be a few different kinds of audiences, and if there are, I expect that their reactions and takeaways might differ a great deal! I hope that the book challenges some of the prevailing assumptions about evangelicalism among scholarly and popular audiences alike. I hope it helps complicate overly-simple pictures of who evangelicals are, what evangelicalism is like, and how and why evangelical culture took on some of its most defining characteristics. I don’t imagine that everyone will like what the book says, and I know that there will be those who disagree with its conclusions. But I hope there are also readers who see themselves or their communities in the stories I tried to faithfully recount. I hope there is someone out there who feels less alone after reading it. At least in my experience, writing a work of history is an inescapable reminder of its contingency, that things might not have turned out the way they did, and I hope that readers can experience that as well.

I love that. I sometimes say to my students that history is a story that we are still in! Thanks for the reminder. Finally, for the many people who want to keep up with you, where can we find you?

The easiest and most frequent place to find me online is on Twitter @isaacbsharp.

Wonderful! Thank you for taking the time today. Can’t wait to read your book. Y’all go pre-order! (Amazon or Barnes & Noble)