Food Deserts in the United States

What is a food desert?

Food deserts are geographic areas where residents have few to no convenient options for securing affordable and healthy foods — especially fresh fruits and vegetables. Disproportionately found in high-poverty areas, food deserts create extra, everyday hurdles that can make it harder for kids, families and communities to grow healthy and strong.

Where are food deserts located?

Generally speaking, food deserts are more common in areas with:

- smaller populations;

- higher rates of abandoned or vacant homes; and

- residents who have lower levels of education, lower incomes, and higher rates of unemployment.

Food deserts are also a disproportionate reality for Black communities, according to a 2014 study from Johns Hopkins University. The study compared U.S. census tracts of similar poverty levels and found that, in urban areas, Black communities had the fewest supermarkets, white communities had the most, and multiracial communities fell in the middle of the supermarket count spectrum.

How are food deserts identified?

Researchers consider a variety of factors when identifying food deserts, including:

- Access to food, as measured by distance to a store or by the number of stores in an area.

- Household resources, including family income or vehicle availability.

- Neighborhood resources, such as the average income of the neighborhood and the availability of public transportation.

One way that the U.S. Department of Agriculture identifies food deserts is by searching for low-income, low-access census tracts.

In low-access census tracts, a significant share (33% or more) of residents must travel an inconvenient distance to reach the nearest supermarket or grocery store (at least 1 mile in urban areas and 10 miles in rural areas).

In low-income census tracts, the local poverty rate is at least 20% or the median-family income is at most 80% of the statewide median family income.

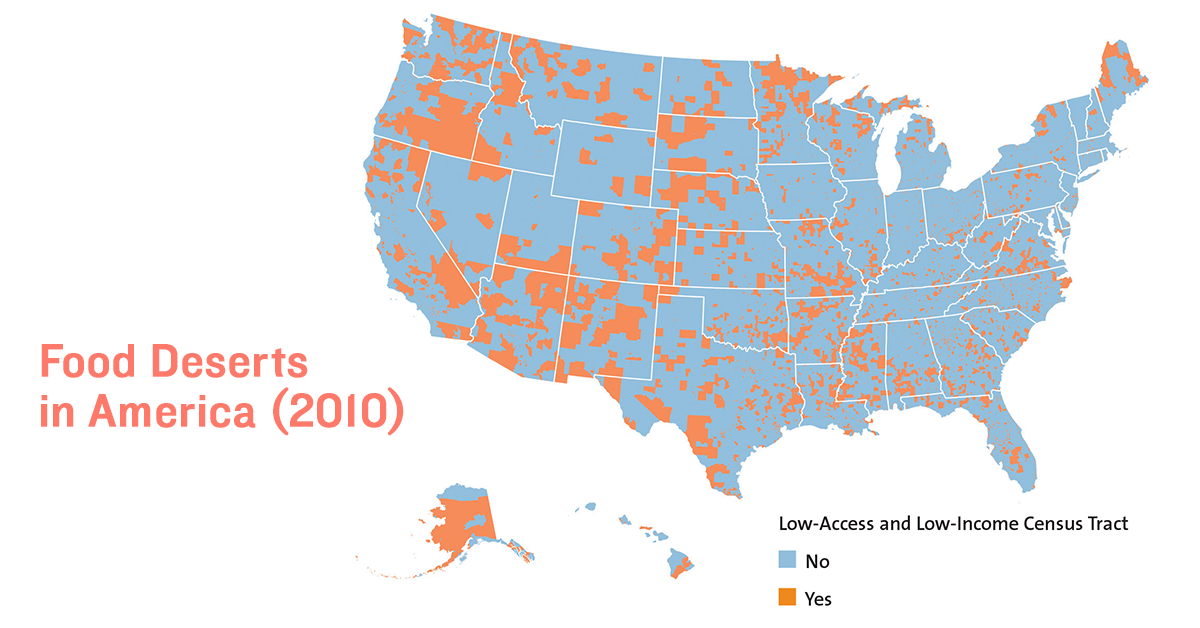

Mapping food deserts in the United States

Source: The Food at Home report by Enterprise Community Partners

How many Americans live in food deserts?

Nearly 39.5 million people — 12.8% of the U.S. population — were living in low-income and low-access areas, according to the USDA’s most recent food access research report, published in 2017.

Within this group, researchers estimated that 19 million people — or 6.2% of the nation’s total population — had limited access to a supermarket or grocery store.

Why do food deserts exist?

There is no single cause of food deserts, but there are several contributing factors. Among them:

- Transportation challenges — Low-income families are less likely to have reliable transportation, which can prevent residents from traveling longer distances to buy groceries.

- Convenience food — Low-income families are more likely to live in communities populated by smaller corner stores, convenience markets and fast food vendors with limited healthy food options.

- Added risks — Opening a supermarket or grocery store chain is an investment risk, and this risk can grow to prohibitive proportions in lower-income neighborhoods. For example: The purchasing power of customers in these communities — including families enrolled in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program — can change dramatically over the course of a month. At the same time, the threat of higher crime rates, whether real or perceived, can raise a business’s insurance fees and security costs.

- Income inequality — Healthy food costs more. When researchers from Brown University and Harvard University studied diet patterns and costs, they found that the healthiest diets — meals rich in vegetables, fruits, fish and nuts — were, on average, $1.50 more expensive per day than diets rich in processed foods, meats and refined grains. For families living paycheck to paycheck, the higher cost of healthy food could make it inaccessible even when it’s readily available.

How has the coronavirus pandemic impacted food access?

The coronavirus pandemic injected even more challenges — both logistical and financial — into the complex field of food access.

As COVID-19 cases rose across the country, restaurants, corner stores and food markets — among other businesses — closed their doors or reduced their operating hours. Residents who relied on public transportation for fetching groceries faced additional hurdles, including new travel restrictions and scaled-back service schedules.

Beyond making it harder to get to the grocery store, the pandemic also kicked off an economic crisis that made it harder for some families to afford groceries. In fact, nearly 10% of parents with only young children — kids ages five and under — reported having insufficient food for their families and insufficient resources to purchase more, according to a fall 2020 food insecurity update from Brookings.

What solutions to food deserts can be pursued?

Environmental, policy and individual factors shape eating habits and patterns — both personally and collectively, according to Joel Gittelsohn, a public health expert at Johns Hopkins University. Within this complex landscape, some strategies for alleviating food desert conditions include:

- Incentivizing grocery stores and supermarkets in underserved areas.

- Funding city-wide programs to encourage healthier eating.

- Extending support for small, corner-type stores and neighborhood-based farmers markets.

- Partnering with the community when selecting food desert measurements, policies, and interventions.

- Expanding pilot efforts allowing customers to use Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program benefits to purchase groceries online.

Casey Foundation resources on food insecurity and food access

The Kids, Families and COVID-19 KIDS COUNT® policy report highlights pandemic pain points, including the uptick in food insecurity across the United States.

Food at Home, a Casey-funded report, explores leveraging affordable housing as a platform to overcome nutritional challenges. The publication touches on food deserts and their impact on communities across the United States.

A September 2019 Data Snapshot shares recommended moves that leaders can take to help families in high-poverty, low-opportunity communities thrive.

National statistics on kids and food insecurity, via the KIDS COUNT Data Center.