COLUMBUS, New Mexico — A fourth-generation rancher who once viewed the border wall project as a blessing now faces a nightmare after construction was stopped 1 mile before being finished, leaving a hole right in his backyard through which he fears immigrants will be funneled.

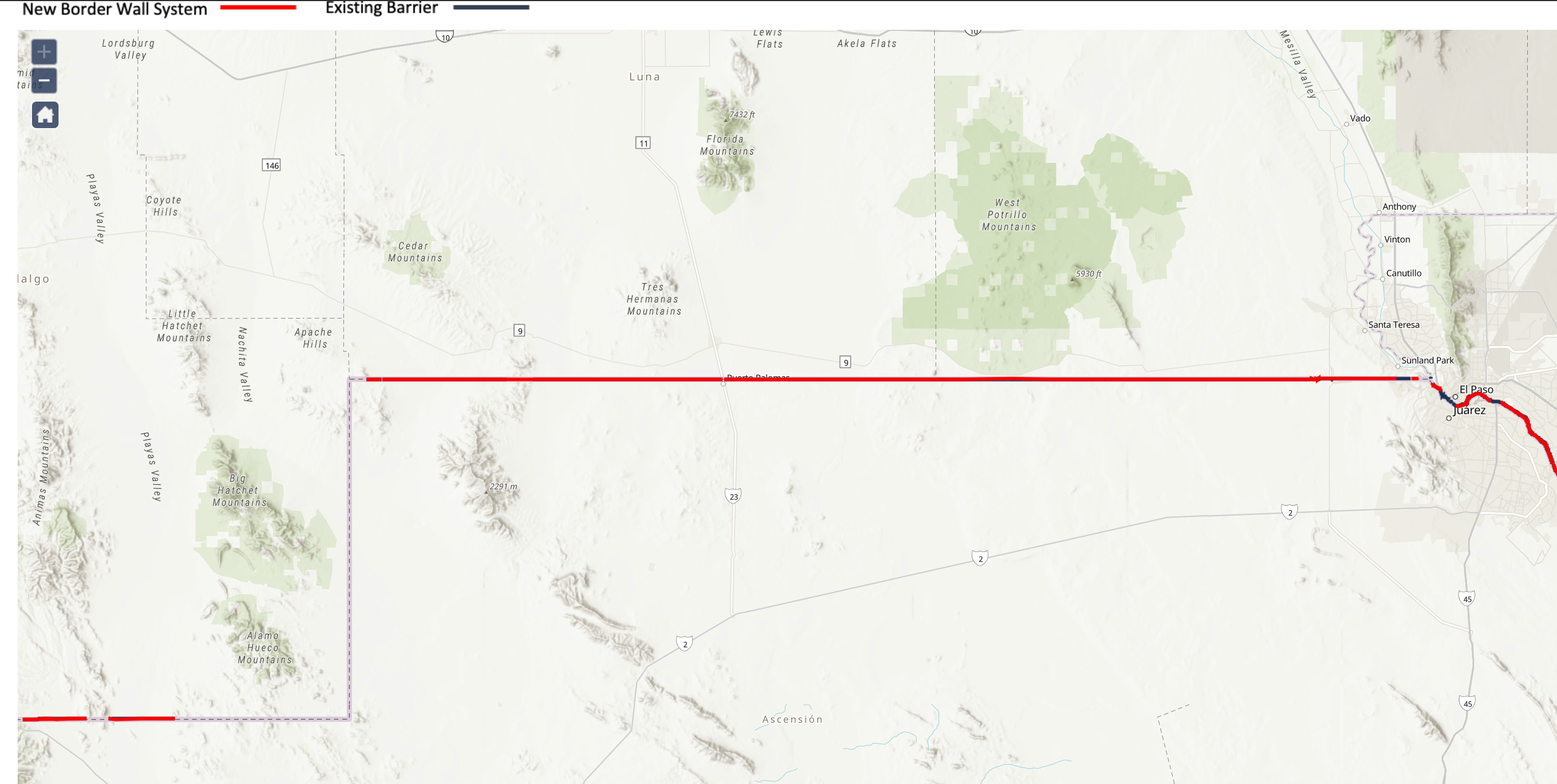

A wall project originating near El Paso, Texas, came to an abrupt end last week near Hermanas, New Mexico, less than a mile short of where it was slated to connect to another wall. Landowner Russell Johnson said President Biden has set his family up as the first spot in the 90 miles to El Paso where people will try to sneak into the country, and Johnson is scared for his wife and kids.

For decades, Johnson’s parents, grandparents, and great grandparents have dealt with the realities of living with nothing more than a barbed wire fence dividing both countries. He is gravely concerned now, having already started to see an uptick in people crossing along his 8.5 miles of border-front property over the past several months.

“Traffic has been picking up,” Johnson told the Washington Examiner during a tour of the land. “Even as the wall construction was happening, it’s been funneling traffic as they keep closing the wall up.”

Relief, and then a nightmare

This specific wall project started just west of Sunland Park, New Mexico, the first suburb to the west of El Paso. It was to run approximately 90 miles west and end where another wall project was being completed. But on Jan. 20, Biden signed an executive order halting all border wall system construction projects on the 1,950-mile southern border.

On Jan. 21, construction crews dropped their tools and parked their machines — leaving the final three-quarters of a mile of border wall unfinished.

Johnson was in disbelief that the workers had come so far and could not finish the final 1%.

“Why are you stopping it now, especially when it’s so close to being finished?” Johnson asked rhetorically. “And it’s under contract. It’s going to cost the taxpayer more for them to pull out and not finish it. So just let them finish it.”

Theresa Cardinal Brown, immigration and cross-border policy director at the Washington-based think tank Bipartisan Policy Center, said the Biden administration should have considered the ramifications of not finishing the project.

“When you take an action at that level, there are on-the-ground consequences. And if you haven’t done a good job figuring out what those consequences are, it overtakes the policy,” Brown said. “Is Border Patrol going to surge resources to that gap?”

CBP did not comment on where the project ended and did not state if it will send more agents to the gap in the wall.

Growing up on the border

The family ranch sits 3 miles north of the border, directly above the gap in the wall. The ranch extends from one mountain range to another.

Johnson has grown up here and spent nearly all his life living here. He said people running over the border in his backyard peaked around 2005.

“There was 500 people crossing that a day, and then, in 2006, that went up to over 1,000 people a day,” Johnson said. “It was nothing to see people just walking down the road. I mean, there was so many people crossing, and Border Patrol was so overwhelmed, that they couldn’t catch them all.”

He has never had his home broken into but said that family and friends have, including one instance in which all the guns in the home were stolen and another in which his parents’ liquor cabinet was “wiped out.”

The barbed wire fence

Migrants and smugglers looking to get over the border use Mexican roads that go right up to the border, then walk a short distance to the barbed wire fence and either climb over or slide under it. Vehicles would drive through or pull the fence down then proceed across.

“What’s really bad about the drive-throughs — they destroy the fence when they do it, which allows Mexican cattle to come north and commingle with our cattle, which we don’t know what the vaccination protocols are over there and everything, what diseases they may or may not have, could be bringing them over here. Or our cattle go south. And when that happens, we don’t ever get them back,” he said.

In 2008, a 4-foot-tall steel fence was installed along parts of the border to stop vehicle crossings. But Russell said people used ramps to drive over the fence, and it did nothing to stop pedestrians. The mountains still had only barbed wire fencing, which vehicles were now driving through to avoid the short steel fences. He says he redid the fence seven or eight times last year.

New steel fence fails to stop border crossers

In 2011, Johnson left the family business and joined the Border Patrol. He said that he is proud of his work but that people in the southwest “hate” agents and that it can be challenging to find a job afterward. He left the Border Patrol in 2016 when former President Barack Obama was still in office and returned to ranching because his father needed help. He and his family moved into his current home five years ago.

Over the past several years, southeastern New Mexico has been one of the busiest parts of the southern border for illegal migration and smuggling contraband. He has seen consistent activity over the past two years. He mentions an incident in which a red pick-up truck crashed into a ditch after the driver tried to race over the border and get away. It was carrying 10 people.

Cameras on his property that are meant to catch game crossing instead show example after example of adult men walking through his ranch.

For all the incidents the camera does catch, there are likely many more that go unseen simply because of the expanse of the ranch.

He carries a gun for self-defense, adding that cellphones do not get service out here, Border Patrol is hard to come by, the sheriff’s department is spread thin, and it is hard to explain your location to someone unfamiliar with the land.

Where is Border Patrol?

The main road that runs through this region is New Mexico 9, a one-lane highway. The closest town is Columbus, whose 1,100 residents are 20 miles to the east. Russell drives 50 miles to go to Walmart, and he does not get phone reception while away from his home, so the family relies on a powerful walkie-talkie system to communicate. His uncle and parents’ families live on their property, but not within walking distance. His other closest neighbor is 16 miles in the other direction.

His extended family and he all live south of the highway. He lamented how Border Patrol agents tend to stay on the highway, not south of it, adding that they are “having a hard time getting Border Patrol to actually patrol the border itself.” It is one of the reasons he feels vulnerable.

His greatest concern with the gap in the wall is the abandoned Mexican village directly on the other side of where construction was halted.

“That spot has been a high threat because of the proximity of that village. It’s an excellent staging ground for people coming across,” he said. “It would take nothing for them to start sending [people or contraband] right through.”

Living cautiously

For the Johnsons, it is sort of a wait-and-see in the coming weeks and months how drug and human smugglers react to the gap and if it becomes a big problem.

“Hope for the best. Plan for the worst,” his wife, Brandy, who has a military background, says is her motto.

Their children are not allowed outside in the yard without their parents.

His wife says there have been suspicious events in the last few weeks, including a random group picnicking in front of their house. She will not read or use her phone when waiting at the spot by their house where the bus picks up the children. She tries to do the same outdoor chores at different times or different days so not to fall into a pattern in case others are watching from the mountain behind their home.

“Having a daughter with windows open at nighttime — I’m like, ‘People are out there. I tell her [they’re] camping, and they can see us, and we need to not have windows and stuff open.’ It’s weird because it’s stuff that you would do if you lived in the city, but we live in the middle of nowhere,” she said.

They say the problem is manageable, but they fear it could become dangerous if the gap in the wall funnels most statewide traffic to their backyard.

“Is it dangerous out here? Yes, it’s dangerous. Am I scared? No. My biggest fear is their safety,” Johnson said, pointing to his family as we stand around the kitchen talking. “But if you’re scared that bad, then you need to leave. But this is our family. This is our business. This is our heritage. You work around it. But I don’t want to say that I’m scared — you’re just cautious.”

The Johnsons said they want to work with lawmakers regardless of what side of the aisle they are on, and they want the hole in the wall filled.

“In New Mexico, we’re very heavily Democratic,” said Johnson, pausing before adding, “How can we find a similar goal?”