Maybe if he'd been born a boomer or a millennial, and grown up with the generational message that you can be whatever you want to be and things will work out, Zack Bauders, 21, would've given more thought to making a living as a professional photographer, like his father. He's certainly got the talent.

His work includes a great action shot he snapped of former Navy quarterback Keenan Reynold, mid-stride, his arm cocked for the throw. He also took a moody picture of a nighttime meteor shower over a mountain and a stream, and contributed regularly to local magazines in his hometown of Philadelphia.

But Bauders didn't graduate from the University of Texas last month with a degree in photography or anything related to the visual arts. Instead he chose actuarial science—a vocation, he believes, that will ensure he always has a well-paying job analyzing risk and calculating rates for insurance companies. To him, the virtual guarantee of future work was one of the career's most appealing attributes. "If you had told me I would be a successful nature photographer or landscape photographer, I would have done it in a heartbeat," he says. "But that's not a sure thing. I knew I was good at math and I could apply those skills and get rewarded for it."

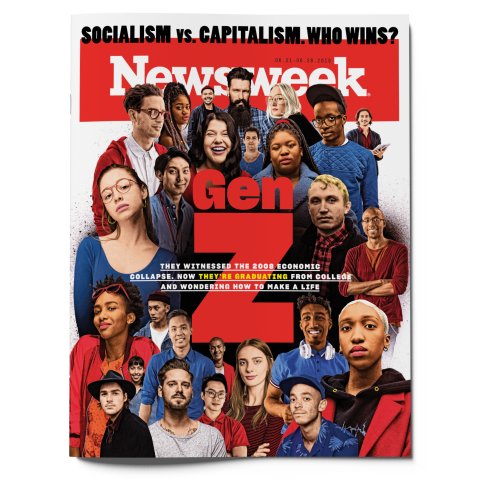

Now that members of Generation Z are graduating college this spring—the most commonly-accepted definition says this generation was born after 1995, give or take a year—the attention has been rising steadily in recent weeks. GenZs are about to hit the streets looking for work in a labor market that's tighter than it's been in decades. And employers are planning on hiring about 17 percent more new graduates for jobs in the U.S. this year than last, according to a survey conducted by the National Association of Colleges and Employers. Everybody wants to know how the people who will soon inhabit those empty office cubicles will differ from those who came before them.

If "entitled" is the most common adjective, fairly or not, applied to millennials (those born between 1981 and 1995), the catchwords for Generation Z are practical and cautious. According to the career counselors and experts who study them, Generation Zs are clear-eyed, economic pragmatists. Despite graduating into the best economy in the past 50 years, Gen Zs know what an economic train wreck looks like. They were impressionable kids during the crash of 2008, when many of their parents lost their jobs or their life savings or both. They aren't interested in taking any chances. The booming economy seems to have done little to assuage this underlying generational sense of anxious urgency, especially for those who have college debt. College loan balances in the U.S. now stand at a record $1.5 trillion, according to the Federal Reserve.

One survey from Accenture found that 88 percent of graduating seniors this year chose their major with a job in mind. In a 2019 survey of University of Georgia students, meanwhile, the career office found the most desirable trait in a future employer was the ability to offer secure employment (followed by professional development and training, and then inspiring purpose). Job security or stability was the second most important career goal (work-life balance was number one), followed by a sense of being dedicated to a cause or to feel good about serving the greater good.

That's a big change from the previous generation. "Millennials wanted more flexibility in their lives," notes Tanya Michelsen, Associate Director of YouthSight, a UK-based brand manager that conducts regular 60-day surveys of British youth, in findings that might just as well apply to American youth. "Generation Z are looking for more certainty and stability, because of the rise of the gig economy. They have trouble seeing a financial future and they are quite risk averse."

What does this mean for the future of this year's graduating class? Will uncertainty and rapid change turn them into a lost generation of anxiety-ridden neurotics, terrified of losing their place in a world of political instability and rampant income inequality? Will they be trapped between the lofty hopes and dreams of their parents and the reality of a shrinking economy and looming climate catastrophe? Or will these constraints spur them to become the most industrious and high-achieving generation in decades? Will it be one or the other—or both? This is the contradiction of Generation Z.

Anxious and Insecure

Alyson Pisarcik, 22, graduated last month from Penn State with a degree in Security Risk Analysis and a minor in Information Science Technology. She says the growing size of her college loans persuaded her early on to set aside her "obsession" with political science and dreams of working for the UN, once she learned of the meager salary she could expect. Now, even though she has secured a job at Accenture, a big consulting company, the looming debt remains a constant source of worry for her.

"Now that I'm leaving college I'm stressed 24/7 thinking about, 'I have to pay this monthly, do I have enough money to move into the city?' All of that stuff that is now encompassed into my life. I know that the loans are always going to be there. It makes you a more stressed person."

Mental health seems to be a theme with Generation Z. College seniors, in a survey last fall by the American Psychological Association, reported the worst mental health of any generation: 91 percent of young adults said they had felt physical or emotional symptoms associated with stress, such as depression or anxiety. They are carrying this anxiety into the workplace. About 54 percent of workers under 23 say they felt anxious because of stress over the past month—topping even avocado-toast-munching millennials (40 percent) and higher than the national average of 34 percent.

The numbers could be pointing to a rise in mental health problems due to the stress of coming of age in the world as it currently is. Or it could have something to do with a newfound willingness to talk about mental health. Experts can be found in either camp, which means both factors are probably at work.

"One of my roommates was going through depression at school," says Pisarcik. "My other one had it younger in life, she was talking about how she didn't want to flip back into it. People are definitely very open talking about what they are mentally going through, more because you feel like everyone is going through stress and stuff like that. You don't feel you're the odd man out if you're going through something."

In colleges across the nation, health services workers are besieged by stressed-out students in need of mental health support. Career counselors say they are busier than they have ever been. Scott Williams, Executive Director of career services at the University of Georgia, has noticed that students are engaging with his offices earlier in their college careers, both in making appointments and in career fairs.

Bob Orndorff, who heads the career services office at Penn State University, has seen a significant increase in demand. Over each of the last two academic years, he says, career coaching appointments have been close to "maxed out." Students are coming in younger, as early as freshman year, with a greater sense of urgency. They are responding to the stress of increased expectations: It's now assumed that a student will seek to participate in at least one internship, and perhaps more.

Much of this anxiety undoubtedly comes from parents, who seem more worried than ever about getting all they can for their kids from their investment of sky-high tuition. Career staff are increasingly being called in for various admissions events to talk to parents and also as part of new student orientation, says Orndorff, a 30-year veteran. Students and their parents on college tours throw around terms like ROI, or return on investment, that would have elicited quizzical looks a generation ago.

With the rate of college graduation higher than it used to be, and the competition for white collar jobs more fierce than ever, a college degree is no longer enough to ensure a dream job.

"I think the old days of saying, 'Well, if I just go to college, I'm set,' are gone," says Orndorff. "Now, I think they've woken up and they see that their older brothers and sisters are graduating with a lot of debt and entering a tough job market out there, that if they don't really lean into trying to find an internship or two or three, they are not going to set themselves apart."

Opinions about what's behind this general rise in anxiety vary widely. But most agree that a combination of factors are at play. Roberta Katz, senior research scholar at Stanford University, who spent the last two years researching a book about Generation Z, says the insecurity that seems to be one of the defining hallmarks of this generation is a function of a quicker pace of change, and the fact that change is unrelenting. For instance, the gig economy has made it harder to predict where you will end up and how long you will stay in your present job. And increasingly wired and globally-connected companies have changed the traditional office culture, making the workplace itself seem portable and less permanent. "We are in the midst of redoing our society," says Katz, "and it's happening really fast and in a really messy way."

These issues have taken a toll on Generation Z. "We need to respect these kids because they are dealing with bigger concerns than we have appreciated," she says. "They are growing up in a different environment. They are really well aware of climate change. They are dealing with threats of gun violence that are very real. And the pace of change is like nothing we have experienced."

Kelley Bishop, head of career services at the University of Maryland, says the most important factor that differentiates the outlook of the kids he sees today from those who came before them have to do with the attitude of their parents. Most millennials, he notes, were parented by boomers—a generation that felt privileged and empowered, growing up in the post-World War II baby boom, raised to be the "Me" generation. The boomer outlook is evident in the iconic film The Graduate, in which 21-year-old protagonist Benjamin Braddock (played by Dustin Hoffman) sleeps with a friend of his parents and falls in love with her daughter. But it all works out in the end, when he breaks up the daughter's wedding and they run off together, chucking caution and the conventional lifestyle of their parents to the wind.

Likewise, boomer parents gave their kids the message that they could do what they wanted and it would all work out; every kid got a trophy, win or lose.

But Generation Z wasn't raised by boomers. They are the children of the famously brooding Generation X, a generation of cynics with a distinctly different outlook than that of those who came before them. The mood of Generation Xers was better captured in movies like "Reality Bites," the 1994 film directed by Ben Stiller, starring Stiller Wynona Rider and Ethan Hawke, in which recent college graduates adjust to a new reality of menial, demoralizing jobs, and worry about contracting AIDS.

"Gen Xers talk about having been latchkey kids, growing up when they were young," Bishop says. "And so there's definitely going to a much more sense of, 'You need to be resilient, you need to learn the ropes, you need to be cautious, you need to be aware, because you may get seriously disappointed'."

He notes that unlike millennials, many in the generation coming up do not "have the same utter trust in the adults to figure everything out and that that they'll make sure everything works perfectly."

Economic Train Wreck

If you ask members of Generation Z themselves, they are most likely to offer a different answer for their anxiety and caution: a hangover from watching the slow motion disaster of graduating millennials, whose boomer-parent-fed hopes and dreams collided with a harsh economic reality. Bauders, who spends a lot of time on Reddit, says his approach to college and career prep has been molded to a large degree by stories about "the doom and gloom of millennials and how they're barely scraping by" and "how awful it is" for kids in their late 20s.

"If I went into college with absolutely no plan, then I would have absolutely no skills to offer in the job market, and then right about now I'd just be going home to live with my mom and go work at a grocery store," he says.

That may be an overstatement in today's hot economy. But it wouldn't have been far off-base a couple years ago. Many millennials did come of age and enter the workforce at the height of a crippling economic recession. And "the long-term effects of this slow start for millennials will be a factor in American society for decades," Michael Dimock, president of the Pew Research Center wrote in an article last January, comparing the conditions Gen Z will face to their older brothers and sisters.

Just in case anyone should forget what the specter haunting today's youth looked like, Dimock pointed to a 2012 Pew report that quantified the disproportionate share of the post-subprime bubble misery shouldered by the millennials. Back then only about 54 percent of young adults between the ages of 18 to 24 were employed, the lowest level since the government began collecting data in 1948. Those with jobs had experienced a greater drop in weekly earnings than any other age group over the previous four years. And the gap in employment between young adults and all those of working age was 15 percent—the widest in recorded history. About half of millennials surveyed said they had taken jobs they didn't want to pay the bills, more than a third said they had gone back to school because of the economy and one in four said they had moved back in with their parents.

"The poor economic climate affected their life choices, future earnings and entrance into adulthood in a way that may not be the case for their younger counterparts, wrote Dimock.

Kyle LeScoezec, who graduated from Ohio State University with a major in business and a minor in engineering this May, says the events of 2008 produced a "healthy pessimistic attitude" that "things aren't always going to work out." He was around 10 or 11 at the time, and recalls his father, who was a financial advisor, having sleepless nights and being constantly on edge. Many of his clients, LeScoezec recalls, were calling him "wondering what's happened to all their money."

By the time he arrived on campus a few years later, LeScoezec, a native of Cleveland, already had an idea of what he wanted to do, choosing Ohio State because it would allow him to study both business and engineering through its integrated Business and engineering program. He has done several internships—including at large and small companies. And for the past year and a half he has been interning at a technology startup in downtown Columbus and starts a job there full-time after graduation.

Even many of those who have decided to pursue seemingly riskier vocations, it seems, have a backup plan. Standing at the ice machine in the hallway outside the basketball courts at the University of Bridgeport gym in Connecticut on a recent day, Katrell Thompson-Nickey, 22, talked about his dreams of parlaying his music major into a lucrative career working as an audio engineer and a songwriter. Just in case that doesn't work out, however, he is pursuing a masters in music education.

"Ideally everybody wants to have a career that you are happy in, but also something that they are stable in," he says. "They want those two things, in their ideal job. I can really pursue what I want to do after this. But I need to have this backup in place now instead of trying to do this in 20 years when I have a family and a lot more responsibilities."

Another Great Generation

There is an upside to this generational caution and pragmatism. Gen Z may just turn out to be the most competent, productive and high achieving generation we've seen in a while. In addition to being the most diverse generation in American history, they also are on track to be the most educated.

In many ways, the same skills they have brought to bear as they have meticulously plotted out their college careers with an eye on a stable job will make them highly effective in the workplace. Gen Zs may be cautious, but they are by no means unempowered. Many are socially conscious and optimistic about the impact they can have. Even more than millennials, employers report, "mission" is important to these recent college graduates and potential employers make sure to articulate it—whether it's curing cancer for Merck, building rockets and weapons to protect the national security at Lockheed Martin, or using technology to improve the lives of those in the developing world and solve problems at IBM. (See Wanted: Cautious Grads Seeking Adventure.)

McKinsey & Company, the consulting firm, conducted extensive research on the current crop of graduates a few years ago in preparation for their arrival as future hires. "Overall they were very hopeful, they felt they have a role to play in changing things they felt were unfair or wrong—and felt they had some agency and could make changes," says Caitlin Storhaug, Director of Global Recruiting Communications & Marketing.

Employers are optimistic about the current crop of potential employees. Once Gen Zs achieve their goal of stable employment, a spirit of exploration and adventure begins to emerge, according to Storhaug and other potential employers. They consistently report a desire to explore different roles, work on career and skills development and move within whatever company they land at.

Gen Zs also bring a technological savvy to the workplace. If Millennials were known as early adopters of social media and other aspects of the digital age—and perhaps for oversharing personal information to their own detriment—Gen Zs are the first true "digital natives." They have learned the perils of digital footprints and online oversharing by watching their older brothers and sisters. They are more careful about curating their digital presence and using it to build a personal brand.

Many of his friends at UT, notes Bauders, have two Instagram accounts: a publicly available one that can be seen by future employers and a private account under a fake name they share only with a few select friends. The practice is so common, there's even a name for it: Gen Zers call their private accounts "finstas," a mashup of "fake Instagram account."

The wild card for employers is to what extent Gen Zs will take an entrepreneurial path rather than a corporate one. Big corporations, which have few qualms about "downsizing" employees when it suits them, are no longer assumed to be the stable alternative. Many Gen Zs, like Elizabeth "Ella" Dana, 22, have already gotten a head start running their own businesses.

In typical Generation-Z fashion, Dana had already built her own business by the time she graduated this year with a double major in film, television and media and the Italian Language from Fairfield University. Over the past two years, she took a series of pragmatic, well-planned steps to ensure that she won't end up living in her parent's basement. She steadily accumulated a roster of freelance clients that now provides cash flow for her company, Ella Creative, which is focused on social media management, photo video content creation and brand work for small companies.

Most of Dana's friends are looking for traditional 9-to-5 jobs to pay off crippling student debt. But many "creatives" have chosen instead to pursue their chosen careers as a "side hustle." Dana, who does not have student loans, prefers to build a business of her own in part because she feels it is more stable in the long term. The idea that a 9-to-5 job will provide stability, she says, is a myth.

Dana got this impression, she says, from listening to podcasts and through personal experience. Her uncle worked at GE in Connecticut and now has to commute more than a hour each way into New York City because the company decided to move. Dana's aunt was out of work for a year when the company downsized.

"If you work for someone else, a lot of people think that, oh that's secure, I have a job, a nine to five, it's going to be there," she says. "But at any point, you can get fired. You can get laid off. Companies are downsizing. If you work for yourself, you're in charge of that. You go out and you find the work, and you're in charge of whether you have a job or not to a certain extent. Obviously, you need to find the work. But at any point if you work for a company, they can let you go, and that job's gone."

Dana's assessment is certainly clear-eyed and pragmatic, and she has an action plan to match. Sounds like a typical Gen Z.