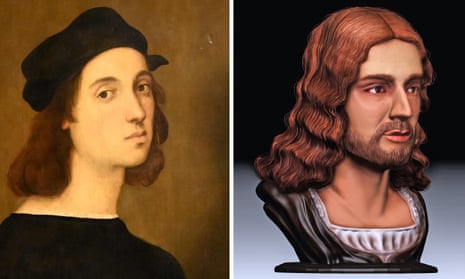

Italian art experts have created a 3D reconstruction of the face of the Renaissance artist Raphael, which they say proves he was buried at the Pantheon in Rome.

Raffaello Sanzio died in Rome in 1520 at the age of 37, eight days after contracting a fever.

The experts at Rome’s Tor Vergata University created the 3D reconstruction by using a plaster cast of his skull that was made after his body was exhumed in 1833. They then compared it with portraits of the artist that were painted by his contemporaries, as well as self-portraits, and concluded that there was a clear match.

It was not certain whether the exhumed remains belonged to Raphael, as other skeletons were also found at the time. Some of them belonged to his students; others were not identified.

Olga Rickards, a molecular anthropologist at Tor Vergata University, said: “This research provides, for the first time, concrete proof that the skeleton exhumed from the Pantheon in 1833 belonged to Raffaello Sanzio and opens the paths towards possible future molecular studies aimed at validating this identity.”

Several museums in Italy are holding exhibitions to commemorate the 500th anniversary of Raphael’s death. The biggest exhibit is taking place at Rome’s Scuderie del Quirinale, where more than 200 of his works are on show.

According to popular myth, the painter died of syphilis. A study by historians, however, published in July, ruled out syphilis, as well as malaria and typhoid, concluding instead that bloodletting, the ancient practice of withdrawing blood as a treatment for disease, contributed to his death. They said he was probably suffering from pneumonia and that bloodletting weakened him further.