Bias

The Accidental Racist

How we unintentionally offend teammates and other sports participants.

Posted August 22, 2020 Reviewed by Kaja Perina

Racism smacked me in the face for the first time in 1964.

I was 12 years old, attending summer camp in upper-middle-class suburbia. My camp group—the “Panthers”—were sitting in a van waiting to be driven to some off-campus activity. We were gabbing, laughing, and carrying on as 12-year-old boys do, when it happened—an ugliness I’ll never forget.

THE JOKE

A camper—whose name will not be identified—told a horribly racist joke. Seated directly across from me was the only black kid in the Panthers. One of the best liked kids in our group, he was happily engaged in our boyish banter. When the joke was told his gleefulness flipped to profound sadness —a look forever burned into my memory.

The van erupted in laughter, except for the victim and me. We were silenced, he in perceived anguish, me in hurt and shock.

Ironically, “the joke” incident occurred within days of the signing into law of the Civil Rights Act of 1964—on July 2—by President Lyndon B. Johnson, and the June 21 abduction and murders of Freedom Summer civil rights workers James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner in Neshoba County, Mississippi.

It was a summer of protests and rioting—triggered by racial injustice—rocking America.

Sound familiar?

WHAT DOES THIS HAVE TO DO WITH SPORTS?

Sports and teams—like everything else—is no place for racism. We define racism—here—as disrespectful, and/or hurtful behavior—often accidental and unintended—triggered by some perceived difference in another person.

The focus—here—is not the systemic or institutional racism highlighted in the media, but rather, instances of interpersonal racism.

Sports participation requires respectful interaction with teammates, coaches, opponents, officials, etc. These people are not going to be exactly like you. They will be of different ages, nationalities, genders, religions, cultures, color, and a few other things. Participants must accept these differences and, respectfully, get along for sports to work.

“The joke”—and the look on my campmate’s face—taught a critical life lesson. We must be aware that what we say and do could be racially—or otherwise—offensive. At times, we all behave in a manner that unintentionally injures. Listen with open mind to those offended and be willing to change.

THE VICTIM

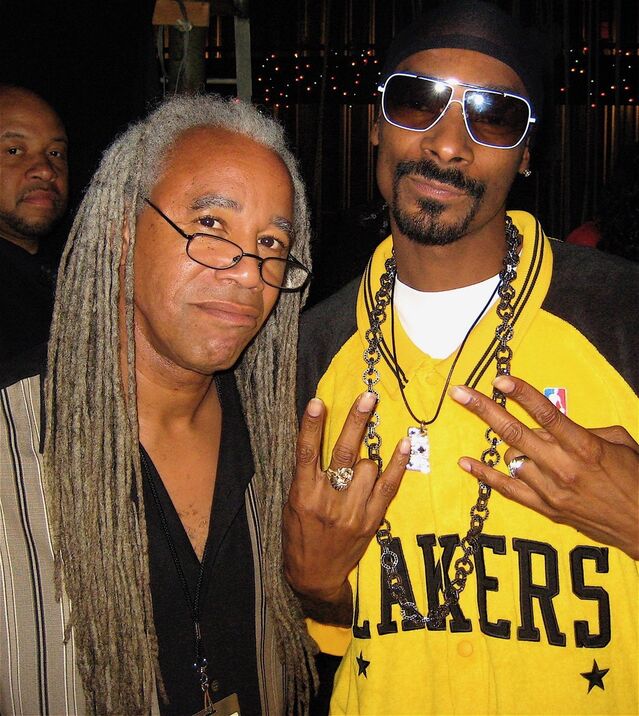

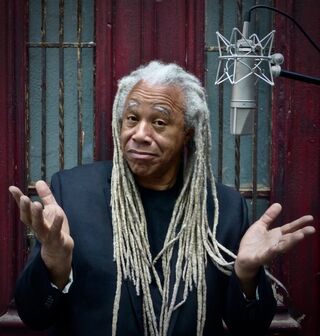

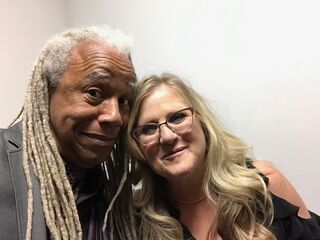

Recently, I decided to find the victim of “the joke.” A Google search quickly revealed a pleasant surprise—my old camp pal is famous.

He is David Fennoy— “Fanny” Fennoy to us 12-year-old day campers. My nickname was “Uncle Udy”—don’t ask.

Fennoy—living in Los Angeles—is a superstar in the video game/cartoon Voice Acting world. He’s the voice of Lee Everett in The Walking Dead and Bo Jackson in ProStars. His video game resume is endless, including characters in World of War Craft, Dota 2, Grand Theft Auto, and Minecraft. He played football at Macalester College (MN).

A call to Fennoy’s agent resulted in a return call from “Fanny” within minutes. After a reunion catch-up, I explained the reason for my call, sharing the camp van story. A three-hour discussion about racism began.

THE DISCUSSION

Fennoy asked to hear the joke. After much coaxing, I relented.

He grunted in disgust at the n-word punchline and to my confused surprise, didn’t remember a thing about the incident. How could he forget?

“I heard so many of them (racist jokes) they just all blend together,” Fennoy explained. “I stopped hearing them, mostly, when I went to Howard University,” an Historically Black College and University (HBCU). He attended Howard after Macalester.

“Up until then I was one of few black people around a bunch of white people,” he continued. Fennoy attended a private, suburban high school, but lived in an inner-city neighborhood of Cleveland, Ohio.

It wasn’t just insulting jokes Fennoy endured in his younger days. There was a daily barrage of other offensive comments and behaviors, mostly not intended to be offensive— “without rancor,” as he put it.

“There were certain comments I didn’t quite understand at the time. I wasn’t sophisticated enough to get them,” Fennoy reflected. “When I went to the private (predominantly white) high school, I would hear things like ‘oh, you’re different from other black people.’ What they’re thinking is their image of who black people are, which was not a positive one.”

“It’s like ‘Oh, here’s one that lifted himself up beyond his people,’ That’s not what they would actually say,” Fennoy clarified. “They would say ‘you’re different.’ They are thinking ‘I know a couple of black people that have got an education and a career, but they’re different.’ “

Fennoy emphasized that these comments were not of distain nor dislike, but of ignorance. “I don’t think they were in full knowledge of what they were saying,” he explained.

Fennoy and I agreed that the “The joke” at summer camp was not intended to offend. The boy who told it was our friend and only 12 years old. It was “without rancor”—an act of ignorance—but still hurtful.

OTHER EXAMPLES OF “RACISM WITHOUT RANCOR”

“I don’t see color” is a common line from people trying to show (unsuccessfully) open-minded unity.

“Don’t tell me you don’t see color,” Fennoy exclaimed. “Yes, you do! That’s b******t. I don’t think people that say that have antipathy for black people, but they are clearly the people that see it (antipathy) but are in denial about it.”

Hint: Saying “I don’t see color”—and similar remarks—is insulting and showcases ignorance.

And then there’s the n-word.

“Rappers are using the n-word all the time,” Fennoy said. “A lot of white kids love rap, so when they’re singing along, out it comes (the n-word). And they may even—among themselves—call each other the n-word. They (white kids) have black friends that they feel they can use the n-word with. Some of their black friends are going to say it’s okay, and some of their black friends are not going to be okay.”

“This can be confusing territory,” said Fennoy. “You’re the white guy and maybe you’ve hung with a bunch of black people for years. You got used to them calling you that (the n-word), and you calling them that, but when you’re in a different group you can’t do that.”

“Don’t use the n-word—ever,” advised Fennoy.

You might think it’s cool, you might think it’s chummy. It’s neither. Don’t risk insulting people for a few moments of thinking you are cool. And of course, there is always the risk of a beat down.

Another form of unintended, accidental racism is when white people start talking or behaving differently then they usually do because they are interacting with someone black.

“You’ve got the white, middle class kid who grew up in the suburbs,” Fennoy explained. “He’s been listening to rap and when he and his white buddies get together they use the n-word and act what they think is black and then they get around black kids with that mess and think they’re connecting with them.”

You are not connecting—you’re being racist and looking foolish. “Use your brain and just be yourself,” advised Fennoy.

Then we have the infamous “some of my best friends are black.”

“Invariably, people that say that are referring to somebody that delivers something for them, or works for them, or somebody they know that they had a meaningless, pleasant conversation with,” Fennoy said. “They’ve never had them over for dinner, they’ve never been to their house.”

You’re not ingratiating yourself, you’re being annoying,

LESSON UP

“I’m not concerned with your liking me or disliking me. All I ask is that you respect me as a human being,” said Baseball Hall-of-Famer and integration icon Jackie Robinson.

The misbehaviors discussed serve as disrespectful, daily reminders to black people that they are viewed and treated differently than other human beings.

Such behavior—not maliciously intended—offends and interferes with success. Being a team requires an all-for-one, and one-for-all approach, not differential treatment based on race, religion, politics, etc.

Strive to treat teammates, coaches, officials, opponents, and anyone else in your life the same—respectfully—regardless of differences.

When we accidentally disrespect, listen openly to those offended, take responsibility, learn, and change your behavior. Defensiveness, denial of responsibility, and failure to change, worsens the situation and contributes to team divisiveness.

Don’t wait to be told you did something disrespectful. Be aware of your behavior, and when in doubt, ask if you have offended and let it be known you are open to being told of your miscue.

“Use your brain and just be yourself,” as David Fennoy would say.