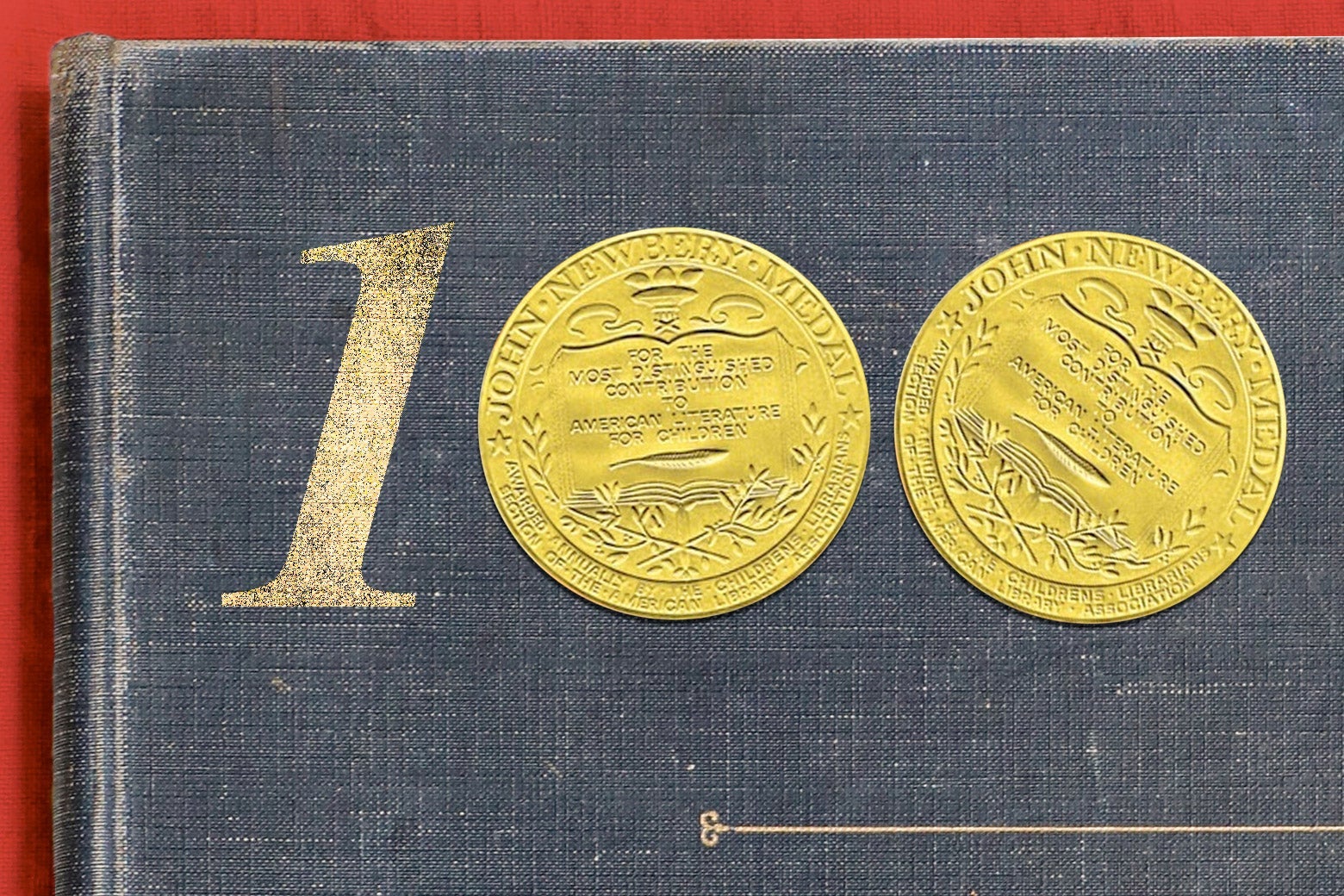

The Newbery Award is celebrating its 100th anniversary in 2022. Such milestones are times of celebration, and merchandising, but also of reflection. Many people perceive the medal as a permanent seal of approval. Bookstores and online algorithms display award winners prominently, and those shiny gold medals on the covers communicate the books’ prestige. On the eve of its second century, the Newbery is now a venerable institution, and its age lends credibility. But are all 100 winning titles worthwhile reading today?

Launched in 1922, the John Newbery Medal was designed to create instant classics, the prize standing in for the test of time in an inspired effort to create an American children’s canon. And it did. Today, nearly all medal winners remain in print, and they appear on library shelves and K–12 curricula in disproportionate numbers. Their frequently refreshed book covers also make them appear indistinguishable from contemporary fiction. In their appealing repackaging, the books represent the perfect combination of old and new, tapping into adult nostalgia and offering the American Library Association’s assurance of literary quality.

In contrast with many adult novels that won accolades decades ago, prize-winning children’s books can have especially long lives. Do the math: Your teacher assigned a 25-year old-book because it was a “timeless Newbery.” And now that book is in your child’s hands, and it’s, what, 50 or 60 years old? That’s in part because there is a common misconception that childhood itself is universal and static. Any childhood “first,” from that first lost tooth to the first time behind the wheel, can feel immutable. Are kids’ experiences really that different than they were a generation ago?

But the world has changed, and the idea of a “typical” child has been blown apart. Many of us are increasingly aware that American childhoods can look very different from one another, varying with race and ethnicity, geographic location, economic status, and many other factors. This has always been true, of course, but until very recently, the imagined child reader was monolithic. So your favorite Newbery from childhood may now seem out of touch, hopelessly uncool. Worse yet, it may feature offensive viewpoints and stereotypes.

Some readers may reject older titles for their objectionable content. But some people feel that recent medal books threaten a long-cherished vision of a universal American childhood experience—a vision they still hold dear. This was the case recently when schools in Katy, Texas, retracted (then subsequently reinstated) an invitation for author Jerry Craft to speak. Craft’s 2020 medal winner, New Kid, depicts a Black boy’s first year in a predominantly white prep school, where he faces frequent microaggressions. Concerned that some readers might experience white guilt, agitators claimed the book ran afoul of Texas’ ban on teaching critical race theory.

The fact that New Kid sits on the same library shelf of Newbery winners as Hugh Lofting’s blatantly racist 1923 medalist, The Voyages of Doctor Dolittle, shows that the award has succeeded in its canon-making project. But the bigger—and arguably more lasting—accomplishment of the Newbery has been stimulating the production of children’s literature in the U.S. Children’s publishing is flourishing, with 32,000 new books for youth published each year, as opposed to 450 at the Newbery’s inception—and many of these titles are of astounding quality. To find those standouts, many people rely on the Newbery and other awards as a baseline filter.

The criterion of prizing for the Newbery (the “most distinguished contribution to American literature for children”) is the same as it was a century ago, but the librarians choosing the books are not as they were. While the earliest children’s librarians saw themselves as gatekeepers for Literature, today’s Youth Services professionals see themselves as information facilitators and youth advocates. The first and 99th Newbery winners present a visual snapshot of the change. The Story of Mankind, by Hendrik Willem van Loon, is a Eurocentric outline history, and history is the most highbrow of genres—especially for youth. New Kid, with its diverse cast of characters, springs from the other end of the genre hierarchy: It is a graphic novel. “A comic!” we imagine the 1922 prize-givers exclaiming in pearl-clutching horror.

The books and the prize-givers have changed, but the mechanism of Newbery prizing has stayed the same: Librarians choose the winners, authors get a career boost, and publishers reap the financial rewards. Plus, the Newbery helps kid lit capture the media’s eye: The intensely secretive selection process culminates in a dramatic, livestreamed announcement of the year’s winner. (This year’s will take place Monday.) The Newbery makes aspirationally high art for children into news.

This is what Newbery founder Frederic Melcher had in mind: Librarians’ professional neutrality would keep prizing above the taint of commercialism, benefiting publishers’ bottom lines and also, of course, children’s minds and spirits. The prize was about building a junior American canon, books that cultivated readers and inspired the highest ideals of democratic citizenship in the nation’s youth. But the result was a canon that is overwhelmingly white and often marked by a colonialist worldview. Today, the Newbery’s mission increasingly encompasses an awareness of past failures to think about all children as future leaders.

Newbery Award Selection committees have responded to the growing influence of the We Need Diverse Books movement and the calls to redress historical misrepresentations by awarding the prize to more diverse titles. Publishers, too, have signed on: As more books by underrepresented authors have captured Newbery gold, the industry has released increasingly diverse stories by an expanding pool of authors. Yet publishers also remain committed to their profitable backlists. They have sought to refresh and remedy older titles that don’t sit well with current sensibilities, especially in regards to race.

Publishers have tried a number of tactics to rebrand older Newbery titles for today’s readers. Recent examples include books repackaged with forewords that tackle the collective discomfort head-on. The 1974 Newbery winner, Paula Fox’s The Slave Dancer, has been criticized for its white authorship and racist framing. But in his 2016 foreword, Newbery Medalist Christopher Paul Curtis, who is Black, places the novel in his own “pantheon of great books” without denying the novel’s centering of the white experience or its painful (if historically accurate) use of racial slurs.

Some introductions serve an entirely different purpose: rekindling child interest. For the 75th anniversary of Esther Forbes’ Johnny Tremain, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt commissioned a foreword by cartoonist Nathan Hale. Set on the eve of the American Revolution, the 1944 medal winner is a staple of school curricula, but no longer flies off bookstore shelves. Hale’s foreword, presented in graphic novel format, orients readers to Forbes’ characters and leisurely narrative style, bridging the gap between the 1940s and 2020s. But Hale’s kid-friendly character guide ignores enslaved characters, who are not central to Forbes’ narrative. In Forbes’s story, Johnny’s transformation into an American patriot involves embracing egalitarianism, but this shift does not extend to enslaved people. This new introduction sidesteps the issue: Its aim is simply to keep the book circulating.

Is that the right approach? Should Newbery gold grant perpetual special status? Or should Newbery winners be treated like any other texts, abandoned when child readers stop reaching for them? Some argue that it’s time to let older Newbery titles fade away. It used to be that Newbery books never went out of print and that libraries had designated shelves of award-winning titles. Books were adorned with Newbery spine stickers, and librarians prepared flyers listing all the Newbery Medal winners by year. But in some places, these practices are being rethought in favor of collections that retain current and popular titles but allow others to be culled.

But what about those books that children continue to seek and teachers assign? It’s past time, many scholars believe, for 20th-century youth classics to be contextualized in the way that 19th-century classics are, with critical scholarship that moves beyond assertions of the books’ aesthetic value. We need critical editions that provide historical context that is accessible to the teachers, librarians, and parents who share these texts with children. (One of the authors of this piece has produced such an edition: Sara L. Schwebel’s Island of the Blue Dolphins: The Complete Reader’s Edition situates Scott O’Dell’s 1961 Newbery winner within the “Vanishing Indian” tradition, demonstrating how the book has participated in the projects of settler colonialism and national mythmaking.)

Fiction authors and illustrators are also revisiting Newbery classics. Responding to art with art, they are crafting stories that are in dialogue with Newbery winners, even as they address the pressing issues of today. The most Newbery of examples is Rebecca Stead’s 2010 medalist, When You Reach Me, a “remix” of the beloved 1963 Newbery winner, Madeleine L’Engle’s A Wrinkle in Time. Similarly, the protagonists of Varian Johnson’s 2018 puzzle mystery, The Parker Inheritance, (a Coretta Scott King Award winner) treat Ellen Raskin’s 1979 Medal winner, The Westing Game, as a key to unlocking their own set of cryptic clues. Both of these award-winning takes respond to contemporary conversations about racism. P. Craig Russell’s 2019 graphic novel adaptation of The Giver functions in a similar way: The ’50s-inspired drawings mean that today’s readers cannot miss the whiteness of the dystopian vision Lois Lowry created in her 1994 Newbery novel.

Some artistic responses are more direct efforts to correct and rewrite. Linda Sue Park’s 2020 Prairie Lotus brings an Asian American girl to a Dakota town straight out of Laura Ingalls Wilder’s 1942 Newbery Honor Book, Little Town on the Prairie. Eric Elliott’s 2013 Dear Miss Karana, originally written in Chamtéela (an Indigenous California language), narrates a Chamtéela (Luiseño) girl’s identification with the protagonist of Island of the Blue Dolphins as well as the conflicted feelings she experiences as she learns more about the real woman who inspired the story. All of these projects—the riffs and the rewrites—solidify the Newbery winners’ place in the canon. They are markers of books that have become classics, stories we continue to debate and reinvent.

This flourishing of activity demonstrates that the Newbery is alive and well at 100. Another marker of vitality is the way Newbery committees are now leveraging the medal’s power to hasten the diversification of children’s literature. The prizegivers know that the award influences publishing trends. Certainly, such trends can shift. The 1980s should give us pause: The turn to diverse authors and subjects in the 1970s, an outgrowth of the civil rights movement, evaporated in the more conservative decade that followed. Yet demographic shifts and changing conceptions of librarians’ professional purpose make a turn away from diversity seem less likely today. And regardless, one thing is clear: We’ve now seen that the Newbery has the capacity to change the canon at lightning speed.

We can’t yet know which recent Newbery winners will fuel decades of debate and inspire creative output of their own, making the transition from “classics by means of prizing” to classics in their own right. But surely some will. What does this mean for the bulging Newbery canon? With a century’s worth of winners, the gold-medal bookshelf is beginning to sag. Some number of the first century’s medalists will necessarily be dislodged from their spots, clearing the way for recent titles that better reflect the concerns, experiences, and preferences of today’s youth. Because when it comes to the canon that matters—the books that circulate for decades—it’s the reading public that shapes and reshapes the Newbery “canon within a canon.”