When I set out to write my first book, I wanted to write a book that examined the very nature of facts and how we turn them into stories. To do this, I knew, I would have to get every fact that was verifiable correct. The more you want to ask the big, shifty questions, the more your foundation must be rock solid.

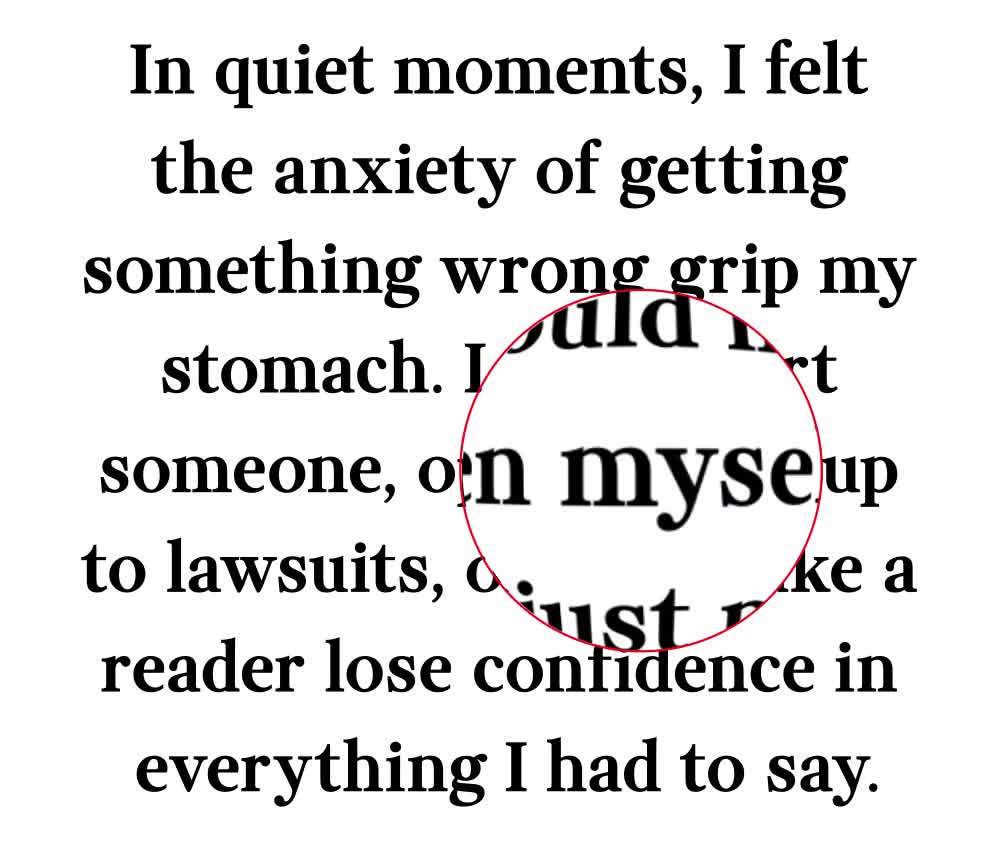

My book, The Third Rainbow Girl: The Long Life of a Double Murder in Appalachia, concerns the deaths of two people who have many living family members, the incarceration of a living man, and a protracted emotional and social trauma of enormous meaning to a great many real and living people in a region with enormous (rightful) distrust of media and journalists. I’d done my best to get the facts correct as I wrote, but I had thousands of pages of archival documents, photos, trial transcripts, and newspaper clippings, as well as hours of interviews. The text had been through too many revisions, both large and sentence-level, for me to count. In quiet moments, I felt the anxiety of getting something wrong grip my stomach. I could hurt someone, open myself up to lawsuits, or just make a reader lose confidence in everything I had to say. Getting my book fact checked was not optional.

Fact checking is a comprehensive process in which, according to the definitive book on the subject, a trained checker does the following: “Read for accuracy”; “Research the facts”; “Assess sources: people, newspapers and magazines, books, the Internet, etc”; “Check quotations”; and “Look out for and avoid plagiarism.” Though I had worked as a fact checker in two small newsrooms, did I trust myself to do the exhaustive and detailed work of checking my own nonfiction book? I did not.

From reading up on the subject and talking to friends who had published books of nonfiction, I knew that I would be responsible for hiring and paying a freelance fact checker myself. This is the norm, not the exception; in almost all book contracts, it is the writer’s legal responsibility, not the publisher’s, to deliver a factually accurate text.

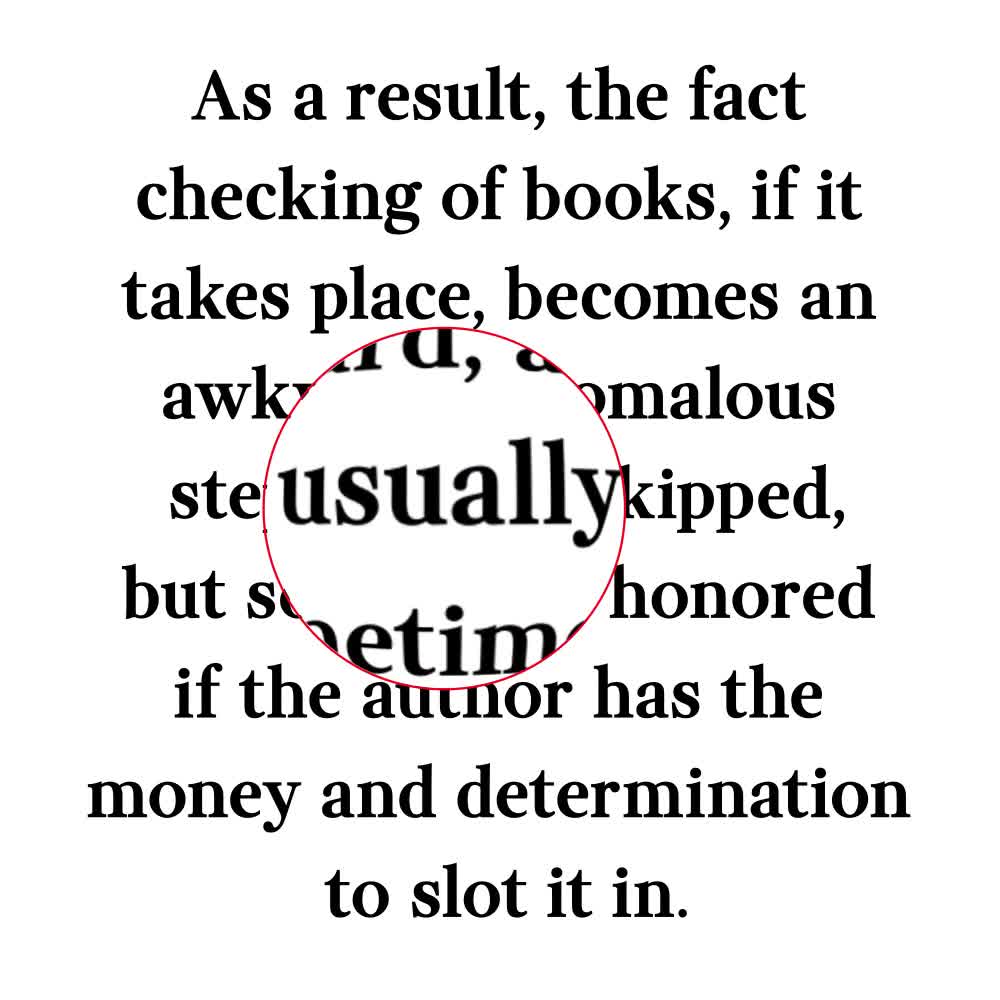

As a result, most nonfiction books are not fact checked; if they are, it is at the author’s expense. Publishers have said for years that it would be cost-prohibitive for them to provide fact checking for every nonfiction book; they tend to speak publicly about a book’s facts only if a book includes errors that lead to a public scandal and threaten their bottom line. Recent controversies over books containing factual errors by Jill Abramson, Naomi Wolf, and, further back, James Frey, come to mind.

Editors who acquire nonfiction books and work closely with authors subscribe to ideas of factual accuracy, but are usually not trained journalists, meaning that they might be unfamiliar with the fundamentals of reporting and fact checking (there are some exceptions to this norm, including recently named publisher of Simon & Schuster and former New York Times writer Dana Canedy). Despite the common sense idea that books are the longer and more permanent version of magazine articles, there is an informal division of church and state between the worlds of book publishing and magazine journalism. The latter is subjected to rigorous fact checking, while the former is not.

There are some reasons for this, including that authors of books are more typically considered experts on their material, while a journalist writing a single article on a topic may not be held to that same standard. Further, magazines typically own the copyright to all pieces they publish, while a book’s copyright remains with the author. All of this contributes to the sense that the magazine is responsible for the accuracy of the words published in their pages, while for a book, it’s the author.

A spokesperson for Hachette Book Group, one of the “Big Five” publishing houses and the publisher of my book, shared this statement with me: "We do have procedures in place to ensure that certain nonfiction books and some fiction books are vetted for libel and other legal issues. Relevant facts may be reviewed during the vetting process as necessary.” But ultimately, the spokesperson emphasized, “The responsibility for the accuracy of the text does rest on the author; we do rely on their expertise or research for accuracy." (Inquiries to Penguin Random House, HarperCollins, Simon & Schuster, and Macmillan went unanswered).

Yet readers and some editors often mistakenly believe that the fact checking of nonfiction books happens somewhere in the typical copyediting process, and in the case of more news-heavy or potentially controversial books, the legal process. But this is not so. These processes may catch contradictions of date and season, name misspellings, or, depending on the copyeditor, glaring errors in research, but they are fundamentally designed to make sure that the book is readable and won’t open the publisher up to lawsuits—not to ensure rigorous accuracy.

Now that the dust has settled and my book has come out, I’ve become curious about whether my experience was typical of nonfiction writers struggling to find a pathway for the fact checking of their books. What I learned made me both more hopeful for the future of fact checking and angrier about the ways that the current publishing landscape keeps both writers and fact checkers disempowered.

Hachette Books, an imprint of Hachette Book Group, bought my book in October 2017. They paid me $50,000 in the first of three installments constituting an advance against royalties. That first payment netted to around $29,000 after agent commission and taxes. This money was supposed to cover the cost of the time it would take me to write the book, as well as all additional research and reporting—to say nothing of the years of research and reporting conducted on my own dime before the book’s sale. I spent about $2,500 on the trial transcript of the case spotlighted in my book, and about $2,000 on travel and reporting. I have no children or adult dependents, and I am in reasonably good health without major medical bills, so I was able to live relatively frugally on the remainder during the period between sale and “delivery” of the completed manuscript to my editor.

My contract stipulated, “The Author warrants, represents and covenants... all statements contained in the Work as published are true or based on reasonable research for accuracy,” and that my book could not plagiarize any other work, “or give rise to a claim of libel or defamation, or invasion of the rights of privacy or of publicity of any party, or violate any law or regulation.” My wonderful editor at Hachette understood from the beginning that it was my intention to get the book fact checked, but confirmed to me that I would have to pay for the checker myself; a legal read to protect Hachette and I from potential lawsuits would, however, be covered.

I had no idea how much money to set aside for a fact checker, so when the time arrived to hire one, I had only a few thousand dollars left. I crossed my fingers that it would be enough. I had worked with a diligent fact checker on a long and convoluted magazine piece; I arranged for her to check my book for about $3,000. My editor gave me as much clarity and notice as he could, yet it was apparent to me that there wasn’t a clear or clean place for fact-checking in the editorial process. Deadlines often changed, and things were on a tight deadline to get advance copies of my book ready for Book Expo of America. Just as we entered the small window inside which my editor had told me we needed to fact check so as not to delay the book’s publicity plan, the fact checker I had hired needed to bow out of the project. I turned to acquaintances and to Twitter.

I received about thirty quotes from freelance fact checkers, most of them young reporters who did freelance fact checking on the side to gain experience and to pay the bills, as well as a few more experienced checkers who had worked for magazines like The Atlantic and The New Yorker. Some gave me payment quotes by the hour, and others by lump sum. My book was 110K words, about a third of which were memoir and about two-thirds of which were heavily reported material with extensive interviews and archival material. The quotes to check it ranged from $1,500 to $20,000. Ultimately, I chose a very capable young journalist and freelance fact checker named Maia Hibbett, who had just gone through the The Nation's renowned fact-checking internship program and was interested in the subject matter of my book. I paid her $4,000 in three installments to check my book in about six weeks.

Hibbett was excellent—and she found mistakes. Lots of them. A few examples: using more updated census data than had been available when I started writing the book, she corrected 24,170 square miles that make up West Virginia to 24,230. She inserted the word “before” into the sentence “Small-scale coal mining had been happening sustainably in pockets of the state since before the Civil War,” noting in the margin that the coal industry in West Virginia was active by 1840. She pointed out that a quote I attributed to a police statement was not ever written down, only said in court. And on and on. But not just small errors—also major errors in timeline, law, and geography. She pointed out mistakes in my presentation of cause and effect, and in my logic of interpreting the meaning of events and statements. “The larger the mistake,” the author Susannah Cahalan told me, “the harder it is for the writer to see it.”

Hibbett and I talked on the phone every day at the height of the fact check. I talked to her while driving, while grocery shopping, while visiting my parents. There is no space in my life that that fact check did not touch. I recall very clearly that by the final week of the process, I would sit in my kitchen with her on speaker phone, my forehead down on the table, responding to her questions for three or four hours. Every writer who has ever been through a rigorous fact check knows that it is as awful as it is wonderful, as mind-canceling as it is comforting—a thing that you do because it is essential not only to make the piece true, but to make it good. The Third Rainbow Girl was immeasurably improved by this process; without it, I would have written a substantially different book.

The copyediting and legal vetting processes (with professionals hired by Hachette) ended up occurring at more or less the same time as the independent fact checking process during the month of February 2019. In the end, I was able to input fact checking changes into the clean master manuscript that was sent to the copyeditor, but it was not always clear if that would be possible. Reduced bound manuscripts, an even earlier version of an ARC, were sent out using the un-fact checked version.

After calling and emailing people I knew—almost exclusively women, for whatever that’s worth—who had published a book of nonfiction in the last five years, what became immediately and abundantly clear to me is that every author’s experience was absolutely distinct and substantively unique.

There is no industry standard for which books get fact checked—the ones that are checked get checked because someone (almost always the author) cared a more than average amount about the truth. There is no industry standard for what it means for a book to be “fact checked.” There is no industry standard for where the fact check should go in the production process of a book. And finally, there is no industry standard for how to hire a fact checker, nor how she should be paid or by whom, nor what should happen if the fact checker’s work isn’t good quality or the author refuses to pay for work already completed.

Of the 18 authors I spoke to, half had not hired a fact checker, but had instead relied on some combination of their own diligence, their publisher’s copy editing process and/or legal vetting process, as well as correcting mistakes in the paperback brought to their attention by readers of the hardback.

Literary agent Chris Parris-Lamb cites money as the main reason writers decline to fact check their books. My research suggests that this is partly true, but not the whole story. I spoke to writers publishing across the genres of memoir, essays, cultural criticism, and reported nonfiction; their reasons for not hiring a checker broke down along lines of both money and publishing experience. Regardless of genre, all of those who did not hire a checker were debut authors publishing their first book, or those who could not afford to pay a checker due to the size of their advance or other reasonable financial reasons—moving, illness in the family, a child’s school costs, etc.

Four authors I spoke to had, like me, hired a freelance fact checker to check their books either in whole or in part. Three of them found their own fact checkers, agreed on a rate, and paid their checkers directly without any assistance from their publisher. These fact checkers charged a fee ranging between $27-$45 an hour, or a flat rate of $2,000 to $10,000 depending on the book’s length, the checker’s experience, and the density of the reporting. $8,000-10,000 seems to be the going rate for a thorough and complete check by a checker who has previously checked a book published by a Big Five publishing house; this rate goes down to $3,000-5,000 for a younger checker working more collaboratively with the author.

All of the authors who hired their own checkers had informal conversations with their checkers about whether or not to call sources or check quotes against recordings, as well as what kinds of facts to focus on checking. That said, most of these authors (including me) did not sign any formal contract or written document with their checker.

One of the authors I spoke to, who agreed to speak on the condition of anonymity, hired a fact checker recommended to her publisher by another of their authors at an agreed-upon rate of $5,000.

“It looked pretty good when it first came back to me, but then I started noticing some things that I had corrected before, which she had changed to incorrect things,” the author told me by email. “Or I noticed that she had caught some errors, but she had corrected them in a way that was still wrong. And she didn't make any notes about how she had sourced her corrections, so it was nearly impossible for me to retrace her steps. And then there were all these things I'd specifically asked her to check, which she completely skipped over. It was a total mess.”

In the end, she paid the checker a kill fee of $3,000. “And then I spent five weeks nonstop fact checking the entire book myself,” she said. “Fact checking was unexpectedly the most stressful part of the whole book process.”

Only one author I spoke to had signed a contract with her checker, which she shared with me; it stipulated how either party could terminate the agreement and how much the checker would be paid if either party terminated the agreement. It did not establish a clear standard for the checker, nor clear consequences if the checker failed to deliver the services or failed to deliver the completed check on time.

Surprisingly and importantly, five authors I spoke to told me that their publishers had indeed paid for fact checking on their books. One of those authors published with Graywolf Press, a small press founded in 1974 and based in Minneapolis. The author didn’t request fact checking, but was told by her editor, Steve Woodward, that the book would be reviewed by a professional copyeditor also trained in fact checking.

“That’s the standard process we use for our nonfiction books,” says Woodward. “We don’t usually hire separate fact-checkers, but combine the process with copyediting, which helps streamline things, and we factor that into the cost.” (Graywolf typically offers significantly smaller advances than the Big Five publishing groups).

Another of the authors I spoke with is published by Bold Type Books (formerly Nation Books). Established in 2000, Bold Type Books is a joint project of the media nonprofit Type Media Center (formerly The Nation Institute) and Hachette Book Group.

"A few years ago, after conversations with our CEO, Taya Kitman, we instituted a policy that everything that came out of our shop should be fact checked,” says Katy O’Donnell, a Senior Editor at Bold Type. (A Hachette Book Group spokesperson notes that O’Donnell is employed by Type Media Center, not HBG). This change came about, she says, “partly because of public scandals and partly because of the rigorous process that all of the projects that come out of our nonprofit undergo.”

All reported books published by Bold Type are fact checked, says O’Donnell, as well as some of the memoirs, but they hope to be fact checking 100 percent of their titles, including all memoirs as well as books of history, by next year. Recently, Bold Type editor Remy Cawley snagged writer Lyz Lenz’s second book, Belabored, as well as books by Marie Claire writer Chloe Angyal and queer sportswriter Britni de la Cretaz.

“Our book went to auction and we got five offers,” says Cretaz. “That they offer fact checking was one of the major deciding factors in signing with Bold Type.”

O’Donnell says that Bold Type typically uses fact checkers who have completed Type Media Center’s internship program, which includes grueling fact-checking training. Bold Type hires the fact checker and pays them directly, meaning that no money passes through the author’s hands; the author is also not directly in touch with the fact checker. However, this practice is not officially written into the Bold Type author contract, a Bold Type author shared with me.

“If we can, we do the fact check before the manuscript goes to the copyeditor,” says O’Donnell. “But that requires authors and editors to be on time. Most of the time it ends up being simultaneous with copyediting.”

O’Donnell told me that the funding for fact checking is possible because Type Media Center's board and donors believe in the importance of facts and investigative journalism. Bold Type is currently working on a fact checking manual to be shared with their fact checkers and authors, says O’Donnell.

“Fact checkers don’t always know what is expected from a book fact check. There isn’t a clear set of standards,” O’Donnell says. This guide would “become an in-house manual for fact checking in the same way that each publishing house has its own style guide for copyedits.”

On the opposite end of the spectrum for publishers offering fact checking services lies the two original content imprints at corporate behemoth Amazon: Little A and Audible. Like Bold Type, Little A hires and pays the fact checker, while authors receive fact check edits simultaneously with copy edits. In 2018, in an unconventional move, Audible began acquiring the audio rights to the works of prominent nonfiction writers like Michael Lewis and Ada Calhoun. The goal was to produce audio books that would drop in advance of their hardback counterparts. Calhoun told me that Audible suggested and paid for the fact checking of her book; it’s no surprise that Amazon has the money.

In the realm of more traditional book publishing, Tim Duggan Books, a prestigious boutique imprint of Penguin Random House, distinguished itself by publishing rigorously reported nonfiction, with fact checking included. By all accounts, Tim Duggan Books, established in 2014, was an experiment to see if a Big Five literary imprint could feasibly make in-house fact checking a part of its model. As it turned out, the experiment was a great success.

Contractually, the writer was still legally responsible for the factuality of their text, but the imprint set aside a pot of money separate from the author’s advance for fact checking, which they then paid to the author, who personally paid the fact checker. It was not required that the author utilize this money, but it was strongly recommended, and most authors writing books rooted in research and reporting availed themselves of it. Before the copyediting process commenced, the imprint found the fact checker and connected them to the writer, but the writer and the fact checker conducted their own correspondence, similar to how a magazine fact checker and writer would operate.

Many in the industry seem to feel that fact checking will never be a standard part of the publishing process for financial reasons—publishing houses just don’t have the money. Tim Duggan Books is proof positive that a traditional literary imprint can find the money to fact check their books—a sum that may actually be less than you’d think. By having a consistent system and a small roster of checkers used routinely, publishers remove the time and labor of finding a checker, establishing parameters and trust, agreeing on a rate, and laying out a timeline—all of which is necessary each time an individual author finds and hires an individual fact checker.

Unfortunately, Tim Duggan Books was recently dissolved due to cuts and consolidations from COVID-19, though there is no reason to think that the budget for fact checking factored into this decision. Upon hearing the news, many of the imprint’s authors and supporters took to Twitter to praise its commitment to fact checking, including The New Republic’s Laura Marsh.

The cost of fact checking a nonfiction book has also gone down in the last ten years, according to an industry insider who spoke on the condition of anonymity. Google’s search algorithms, which automatically sort through hundreds of billions of webpages and rank the results based on relevance and credibility, have improved dramatically in the last ten years, and as information that would previously have been housed only in print libraries or archives is digitized, the cost will only continue to decrease.

“I’ve noticed a change even in just the past few years,” says Hilary McClellen, who has worked as a fact checker since 1998. “It seems like Google has a lot more books digitized and searchable than even a few years ago, and Amazon can be used for book searching cross reference if the pages are missing in Google. I still have to make trips to the library for print or archive on some projects, but it’s not the day-long event it was years ago.”

There are also ethical and power imbalances for the fact checkers themselves embedded into the current state of nonfiction book fact checking affairs. In broad strokes, hourly rates are more favorable to fact checkers, while lump sums are more favorable to writers. With an excess of qualified freelance fact checkers, it’s the writer who often ends up with the choosing power of being “the customer.” My own fact checker, Maia Hibbett, accepted the lump sum I paid her, she says, despite originally asking for an hourly rate, because she was inexperienced and didn’t have any other work; some weeks of steady employment, she figured, were better than nothing.

“I can see it becoming very easy for a fact-checker to end up working for as little as $10 or $12 an hour if they sign on to check a book for a low flat rate,” says Glyn Peterson, a seasoned fact checker who recently worked on Susannah Cahalan’s second book, The Great Pretender.

“It's difficult to know what you should demand, because you can only base your expectations off of your own experience or word-of-mouth, and there's no one to back you up if an employer resists what you're asking for,” says Hibbett. Full time fact checkers for magazines such as New York, where she is now employed, offer membership to their union, a chapter of the NewsGuild of New York. There are some freelancers' unions, she notes, including Freelance Solidarity Project, which is part of the National Writers Union.

“It seems inappropriate and counterproductive that the writer, and not the editor, decides which fact-checking changes to accept or ignore,” says Peterson. “I can see situations in which writers decide to ignore fact-checking suggestions, letting potentially significant errors remain in their books. When checking for magazines, fact-checkers have more power to advocate for their work, because they can go to editors with their concerns if the reporter they are working with refuses to address major errors.”

No such system exists for independent fact checking, as fact checkers are often not in touch with the editors working on the book they just fact checked. It is also unwise on so many levels to have the person who signs the checks (or Venmos the money) be the same person whose work the checker is being paid to call into question. Further, when the writer and checker are working independently rather than within the system of a magazine or publishing house, the writer herself, as the employer, has the final say in the process, a strange state of affairs when it comes to the truth.

The obvious solution is to institute a common set of guidelines that set expectations, rates, and protocols for fact checking. Setting these expectations must be the responsibility of publishers, not authors.

Editors and publishers may have to bear in mind that the range of books published by an imprint may be extremely vast, varying from memoirs to current events to true crime, all of which demand different levels of legal vetting and fact checking. Editors also typically struggle with the pressure to schedule books far in advance, and as the promised date of delivery to the sales team approaches, delays accumulate, meaning that the timeline becomes crunched. The guidelines and protocols for incorporating fact checking into the production process must be fluid; they might involve the kind of prioritizing of resources that many publishing houses already apply to legal vetting, where they pay for the books that really need it to be legally vetted, while the ones that don’t are not vetted.

But the reason why the publishing industry has been slow to implement such guidelines for fact checking may lie further down in the foundation of the whole system. Without widespread consumer awareness that most books are not fact checked, or about which imprints publish which books, there’s no real reason for publishers to care about fact checking. If it comes to light that a book contains major errors, it’s the author, not the publisher, whose reputation takes the hit.

“No one looks at the publishing house's name on the book they bought four years ago when Newsweek exposes it as inaccurate and says, ‘I'll never buy a book published by them again!’” Scott Rosenberg of the now-defunct service MediaBugs told The Atlantic in 2014.

Meanwhile, the stakes of not fact checking books only continue to get higher, as it’s become easier and easier to destroy a book’s credibility with a few clicks.

“If you’re writing a remotely controversial book, there’s going to be an active audience that’s invested in discrediting it,” Kyle Pope, the editor and publisher of the Columbia Journalism Review, told The New York Times.

However, the gap between publishers and readers may be closing. We are in the midst of a moment where ordinary citizens are more invested than ever before in interrogating who gets to determine what counts as the truth in the stories we tell.

In the past six months in the world of media and publishing, we have seen resistance to the status quo at levels of magnitude previously unimaginable. After an employee walkout across several of their imprints, Hachette Book Group dropped its plans to publish Woody Allen’s memoir. Macmillan, which houses Flatiron Books, agreed to substantially increase its Latinx representation both in its authors and staff after widespread criticism over the imprint’s handling of the novel American Dirt. Top editors at Bon Appétit, the New York Times, Condé Nast Entertainment, Refinery29, Okayplayer, Variety, and The Philadelphia Inquirer have all “resigned or stepped back,” wrote Vulture, in its comprehensive list of recent media reckonings in the wake of last month’s anti-racist uprisings against the state-sanctioned murder of Black people.

“There is also a systemic issue here,” wrote Anand Giridharadas in his scathing New York Times review of Jared Diamond’s book Upheaval: Turning Points For Nations in Crisis which looks at what makes some nations able and some unable to recover from times of turmoil. “The time has come for those of us who work in book-length nonfiction to insist that professional fact-checking become as inalienable from publishing as publicity, marketing, and jacket design.”

I agree. The more we ask the big, shifty questions about power and privilege and truth, the more our foundation must be rock solid. Editors must insist on fact checking budgets for their authors, and authors must keep insisting for them such that we can all pay fact checkers fairly. Agents must get involved too; during the course of contract negotiations, other services such as a photography budget and permissions clearance budget are battlegrounds that publishers do sometimes pay for.

“Over the last year, deaths, retirements and executive reshuffling have made way for new leaders, more diverse and often more commercial than their predecessors, as well as people who have never worked in publishing before,” the New York Times recently wrote. “Those appointments stand to fundamentally change the industry, and the books it puts out into the world.”

Investing in fact checking is within our grasp; all we have to do is try.