Today’s guest post is excerpted from So You Want to Publish a Book? by Anne Trubek (@atrubek), founder and publisher of Belt Publishing.

Each book a publisher launches is its own miniature, stand-alone start-up. Every book is a gamble. Publishing could have a game table on the floor of a Vegas casino, nestled between blackjack and roulette. Bet on which title will earn out, and which will fail. When a title doesn’t break even, the casino swipes the chips off the table. But when a bet wins, it can make up for all those losses. A few bestsellers can support a press despite many money-losing titles.

So how do publishers decide which books to bet on? There’s lots of risk involved when you take a look at a few words sent via email and decide that those words might, in one to three years, end up selling enough copies to earn back the money that you spent to make those words into a book, and then earn a little more so the publisher can take a little bit of money home herself.

Publishers ask two main questions, and they’re the same two questions any capitalist or gambler asks: how much should we stake, and how much might we profit?

To answer those questions, most publishers do a ridiculously complicated set of projections on a profit and loss spreadsheet (P&L). This process involves guesswork into a number of different categories: how much a book will cost to print, how many copies will sell, how many ordered copies will be returned, how much the author will receive in an advance, what the list price will be, what trim size it will have, how much money it will take to market and publicize the book, whether it will be hardcover or paperback, if it will appeal to distributors who help sell the title to accounts like Amazon, Barnes & Noble, and independent booksellers.

Some of these numbers are based on actual data, some are good estimates, and some are inferences based upon past experience. But most of them are magical fairy dust wishes. A P&L is basically a work of fiction, make-believe cells that tally up all the costs and revenue for a project that will not hit the market for another few years. It makes the decision to publish a book look more like a sound business plan than a gut instinct that a little ball will fall on number thirty-one on the wheel, but in truth, roulette may be a good metaphor. It’s silly, really, but it’s the practice of the industry.

Complex and chance-centric as they are, P&Ls provide crucial insight into the business of books. Even if they are often inaccurate or useless for publishers, they are key for anyone interested in the cogs of the industry, and those who assume publishers de facto profit from the labor of writers.

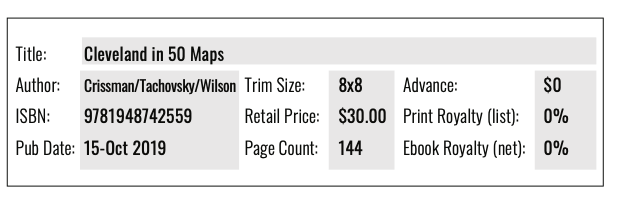

Allow me to walk you through one Belt Publishing P&L that we created to decide whether or not to publish a book called Cleveland in 50 Maps. I have fudged some of the numbers so I don’t reveal the actual pay for various contractors, but the whole is still pretty accurate. I also chose a title that was written in-house by staff, which means there were no royalties or advances. We also entered these numbers before we had a manuscript, or a printer quote, or any of the numbers we entered into the cells. We simply guessed. Like I said, a P&L is a work of fiction.

In the top section, we entered our prospective trim size, list price, publication date, and page count for the book.

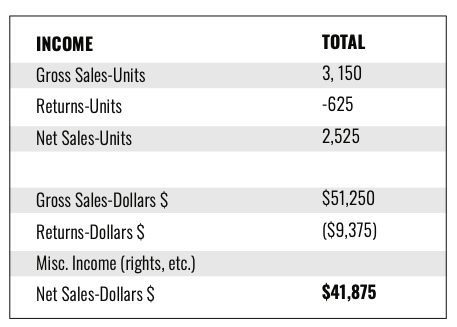

Then we made up some sales numbers—this was one year before the book actually went on sale. We guessed our distributor would order 2,500 copies for this book. Of those, only 1,875 would actually be sold because of the dreaded returns system. (Any book can be returned by a store or distributor to the publisher for full credit.) We hoped for a robust 600 copies that we would sell directly to consumers because we are based in Cleveland and have a lovely crew of fans who understand how important direct sales are to our business model. Under that number we excitedly entered zero returns. Then we added a modest number of ebook sales. (This title is heavy with graphics, and ebooks are notoriously graphic unfriendly.) Usually royalties and advances would be entered here as well, but this book was a special case in that regard, and our costs were lower here as a result. You can see where we would have entered them in the column reserved for advances and royalties above.

According to this model, we would net about $42,000 in sales from this title. Eventually. There is no timeframe on this P&L; it covers the life of the book. Most sales occur in the first ninety days after publication, but a book that becomes a strong backlist title can continue to sell well, if at a slower pace, for years afterward. For Belt’s cash flow purposes, we want to hit our net sales number about twelve months after publication, which is about twenty-four months after we create the initial P&L.

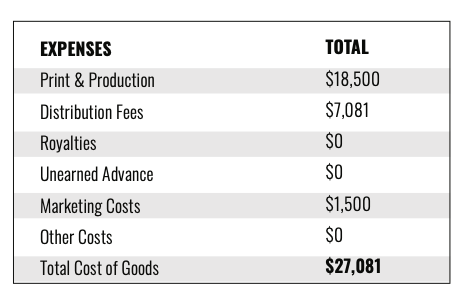

But wait: that $41,875 figure isn’t profit. It’s simply the sales. We still need to count up our expenses, estimating what the book will cost us to make and sell.

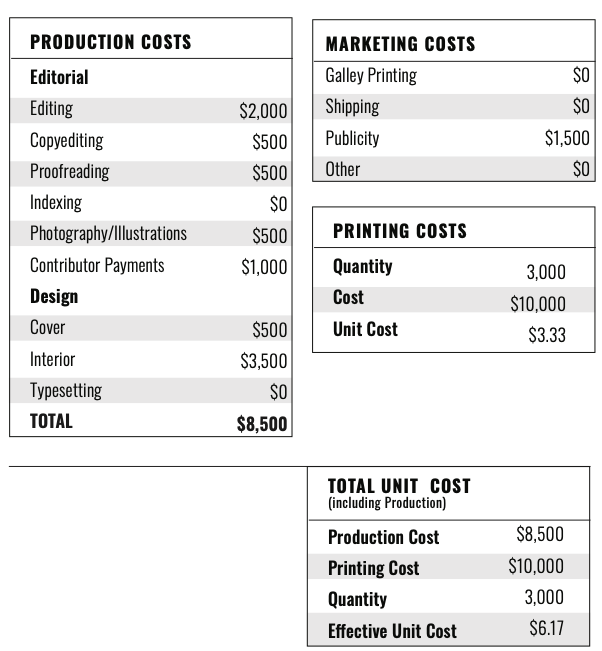

The single largest production expense for most books is printing. Paper is expensive! In our P&L, we estimated that this full-color, hardback book of 150 pages would cost $10,000 if we printed 3,000 copies, or about $3.33 per copy. This is a much higher per-unit cost than our more common 200-page paperbacks, which cost between $1 to $2 per unit.

Cleveland in 50 Maps also had a higher retail price of $30, compared to the $16.95 we usually charge for our paperbacks. We estimated that our distributor, who helps us sell copies, would receive about $7,000 for their work on our behalf. (Remember: these are not real numbers, but accurate ballpark estimates. The amount a distributor charges a publisher cannot be revealed publicly.) We added another $1,500 to our production expenses to publicize the book—sending press releases to local media and bookstores to let them know about it and organizing events to promote and celebrate the title.

But wait—there are more expenses! We have to pay an editor, a copyeditor, a proofreader, a cover designer, an interior designer, and others who contributed to the book. We also need to figure in the cost of securing permissions for images. If we are going to make advance copies of the book to send to media and booksellers, we also need to add in those costs, as well as the postage required to ship them.

Below, you can see the hypothetical costs for all of these components of book production. Note that the P&L doesn’t include the costs of a publisher (me!), or office space, or the labor to ship copies. These are considered overhead and might be included in a flat percentage at other publishing houses. But to keep my explanation as simple as possible, I have not included those.

Add all of those numbers together and the total projected cost to bring Cleveland in 50 Maps to readers is $27,081. And if all these numbers prove true, we will make a profit of $14,794, a 35 percent margin.

Again, this was all conjecture when we initially created it. But it turned out to be fairly accurate to reality. This is not always the case. Some P&L projections wildly diverge from actual P&Ls. The single key factor is sales. If we had projected we were going to sell 3,000 copies of Cleveland in 50 Maps and only sold 200, we would have lost money. And this often happens. As I mentioned earlier, conventional wisdom says it happens about 80 percent of the time.

But once in a while—oh, say, one out of five times—a book’s sales far outstrip expectations. Books that sell far more than projected are the backbone of publishing. For example, pretend that instead of $14,000, we netted $100,000 from Cleveland in 50 Maps. Every title holds within it that possibility (as opposed to, say, a restaurant serving steak: it might make profit from every filet mignon it sells, but it will never sell just one steak that quadruples that profit.) And in publishing, that one jackpot can cover many bad bets.

The ability to bet more money on more books is a key difference between independent presses and conglomerate ones. Usually, a conglomerate press can bet a $100,000 advance to an author three years before a manuscript is due, and five years before the book will be published, in the hopes that it might sell enough to profit the company $1,000,000 another two years after that, when the money from sales actually comes in. If they lose the bet, they can write off that advance, and all the other expenses, as a loss. Usually, though, an independent press can neither wait that long nor risk that much money.

For authors with contracts for conglomerate houses, the advantage is that they receive more money up front. But the disadvantage, more often than not, is that failure is built into the deal—most authors will never sell enough copies to receive royalties after the book is released. With independent presses offering smaller, more realistic advances, chances increase that an author might outstrip expectations and receive royalties.

Basing all your business decisions on spreadsheets that are created years before any of the actions the numbers signify occur may not be the healthiest or most accurate method. And at Belt, we regularly make decisions based on non-P&L factors; often, we skip this step entirely. Sometimes, we publish a book because the staff thinks it would be really fun to do so, or it is right up our alley interest-wise, and even if we may not profit, we likely will not lose money on it. Often, we “take a flyer” on a book by an author with no platform or previous publication track record, but who writes such a compelling proposal we want to give them a chance. Other books just seem so “Belt-y”—they represent exactly why we decided to start the press—because they tell an untold regional history or because they are intellectually rigorous without being pedantic—that we have to publish them to stay true to who we are.

Note from Jane: If you enjoyed this post, be sure to get a copy of So You Want to Publish a Book? by Anne Trubek.

Anne Trubek is the founder and publisher of Belt Publishing, and writes the popular newsletter “Notes From a Small Press.” She is the author of The History and Uncertain Future of Handwriting and A Skeptic’s Guide to Writers’ Houses, and the editor of Voices from the Rust Belt, The Cleveland Neighborhood Guidebook, and Rust Belt Chic: The Cleveland Anthology. She lives in Cleveland.

This is a great post, too, for SELF (Indie) author/publishers. Just take out the line items that DON’T apply (e.g., Interior Design if you do your own formatting) and ADD items that do (e.g., Royalties!). I have similar P&L charts on my Indie books.

Wow. This was… enlightening. Thank you.

My head hurts. This is too much like math. 🙂

Excellent information, Anne. I’m sure it will help many writers.

Thanks for the Fact of Life. The sooner a writer learns all this, the better. Helps focus one’s intentions so as to set realistic goals. Just like to mention that I’ve made way more money on two self-published books than on three traditionally published books. I knew my local market and above all, I’m having fun doing it. Greetings from the great Northwest.

A very clinical take on the expenses of publishing and justifications for choosing one book over another. Yet we have seen recently with #publishingpaidme that publication is more than a numbers game. Projected sales always contain traces of racial biases.

Very helpful article. I feel much better about my expenses for self-publishing. This also explains why many books are staying in ebook format without the expense of printing. Printing eats revenue.

[…] a guest post at Jane Friedman’s blog, Anne Trubek, founder and publisher of Belt Publishing, and author of So You Want to Publish a […]