A 59-year-old North Carolina man died Monday, July 22, from an infection caused by the free-living amoeba Naegleria fowleri, aka the “brain-eating amoeba.”

According to state officials, the man fell victim to the single-celled organism after swimming at the Fantasy Lake Water Park in Cumberland County on July 12, 2019. Laboratory testing at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention later confirmed the infection. Though N. fowleri are rare, they’re almost always deadly, which has health officials calling for greater awareness.

"Our sympathies are with the family and loved ones," NC State Epidemiologist Zack Moore, MD said in a statement. "People should be aware that this organism is present in warm freshwater lakes, rivers and hot springs across North Carolina, so be mindful as you swim or enjoy water sports."

Profile of a killer

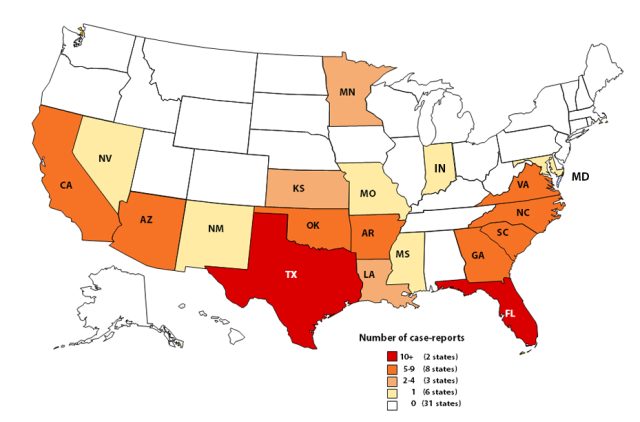

N. fowleri is a heat-loving amoeba, known for striking swimmers during sweltering summer temperatures (it prefers temps up to 115°F/46°C). However, the wee critter is actually ubiquitous in the environment and distributed worldwide. It hangs out in all kinds of soils and freshwaters, surfacing not just in lakes, rivers, and geothermal waters, but in industrial cooling ponds, poorly-kept swimming pools, and domestic water pipelines warmed in the sun. Worldwide, it’s often found in tropical areas but has infected people in the Czech Republic, New Zealand, Belgium, and Japan. In the US, it most often kills in southern states, but the amoeba has popped up in states such as Minnesota and Indiana.

Still, it’s only in very specific circumstances that N. fowleri turns deadly to humans. In fact, between 1962 and 2018, US officials have only caught it infecting humans in 145 cases, despite its pervasiveness in the environment. Worldwide, there’s only been around 300 or so cases in that time frame.

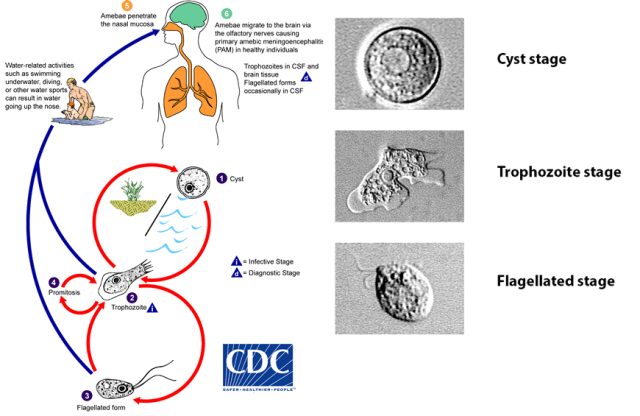

A vast majority of the time, N. fowleri isn’t a savage pathogen but a humble protist quietly grazing on bacteria and yeast cells that cross its path. This low-key lifestyle only seems to change when N. fowleri somehow gets flushed directly into a human nose. This tends to happen when people are in splashy water parks, jet-skiing, or irrigating their sinuses with tap water that hasn’t been disinfected, boiled, or filtered. No other means of exposure seem to cause trouble; inadvertently swallowing N. fowleri is harmless, for instance. But in a nose, things get ugly.

When N. fowleri finds itself shoved into a schnoz, it gets its footing by gripping the mucus membrane in the nasal passage. It then heads deeper, inching along olfactory nerves as if walking on a tight-rope to the brain (these nerves transmits input from smell receptors in the nose to the brain.) But, before it makes it to the brain, it has to slip through the cribriform plate, a grooved bone at the roof of the nasal passages that allows passage of the olfactory nerves through tiny holes. The cribriform plate tends to be more porous in children and young adults—who also appear to be more susceptible to N. fowleri. Of the 145 known cases in the US, 121 of them (85%) were in children and teens.

Whiff of doom

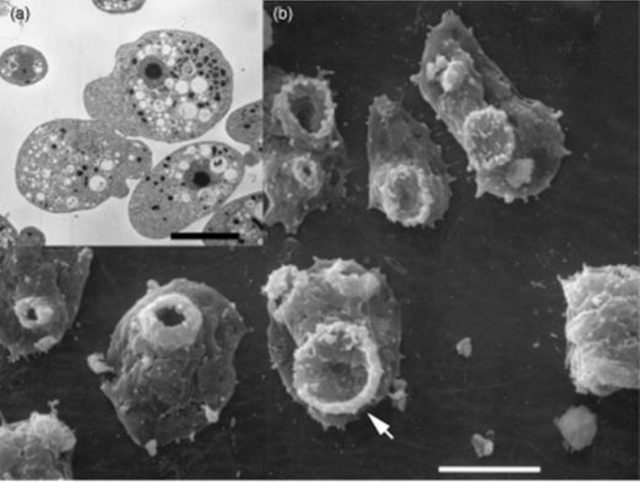

Once through the plate, N. fowleri gets into the olfactory bulb—the structure in the forebrain involved in smell. There, all hell breaks loose. The immune system swiftly wages war when it detects an invader within the central nervous system. N. fowleri, meanwhile, goes back to grazing as it normally does in soils and water. But, of course, its meals are no longer environmental bacteria and yeast cells, instead they're immune cells and brain tissue.

To feed, N. fowleri uses specialized structures on the surface of its cell body, called simply “food-cups.” These are suction-cup like features that ensnare and absorb food. The protist also oozes enzymes that burst and destroy human cells and nerves.

The combination of a feasting amoeba and a blizzard of immune responses leads to significant tissue and nerve damage, and ultimately—most of the time—death. The condition is referred to as PAM, primary amebic meningoencephalitis.

For the PAM victims, the start of the onslaught is marked by a severe headache, fever, chills, and sometimes nausea and vomiting, usually anywhere from one to nine days after an exposure. The symptoms progress to those seen in meningitis, such as stiffness in the neck and hamstrings, as well as sensitivity to light, confusion, seizures, and coma.

Because there are so few cases of PAM, researchers haven’t been able to conduct any trials to figure out which drugs or drug cocktails work best against the amoeba. Treating doctors often use large mixes of antibiotics and antifungal drugs.

One of the most common treatments is amphotericin B, an antifungal drug that has proven lethal to N. fowleri in lab studies but has use-limiting toxic effects on the kidneys. The broad-spectrum antimicrobial miltefosine has also shown promise in some cases. It was originally developed to tackle breast cancer, but the drug became the leading option to treat another parasitic infection, leishmaniasis.

Lucky ones

Worldwide there are only a handful of cases of people surviving PAM. Five well-documented cases have occurred in North American: four in the US, and one in Mexico.

The first survivor was a 9-year-old girl who fell ill in 1978. She was successfully treated with amphotericin B, but subsequent lab tests suggested that the invading amoeba was less virulent than other strains of N. fowleri. Next was the 2004 report of a survivor in Mexico—a 10-year-old boy fell ill after swimming in an irrigation canal and recovered after a cocktail that included amphotericin B.

The US went 35 years without another survivor. In 2013, two children survived, but they had different treatments and outcomes. The first was a 12-year-old girl exposed at a water park in Little Rock, Arkansas. Her symptoms were spotted quickly and she was diagnosed within 30 hours. Doctors immediately started her on a large cocktail of drugs including amphotericin B and miltefosine. They also used medically-induced hypothermia to reduce her brain swelling. The girl made a full recovery.

The second survivor in 2013—an 8-year-old boy—was also treated with a large cocktail of drugs including amphotericin B and miltefosine. But he was diagnosed and treated only after days of symptoms. He survived but suffered what is likely permanent brain damage.

The fourth and final survivor was 16-year-old boy infected in the summer of 2016. He was diagnosed quickly and got the same treatment as the 12-year-old girl. He, too, made a full recovery.

The cases offer hope that one day all PAM victims will be able to be treated and saved. But, with a less than 3% survival rate currently in the US, it’s best to try to avoid getting infected in the first place.

Prevention

To avoid getting a brain-eating amoeba while swimming, experts recommend trying to avoid warm freshwater sources when possible, opting for well-chlorinated pools and saltwater instead. If you do swim in warm freshwater, try to minimize jumping, splashing, and dunking. Plug your nose, or use a nose clip to avoid getting water in your nasal passages. Also avoid stirring up sediment in shallow waters.

For sinus rinsing, the CDC recommends using store-bought distilled water, boiled tap water, or water filtered with pore sizes one micron or smaller (the labels typically include “NSF 53” or “NSF 58” or contain the words “cyst removal” or “cyst reduction”).

reader comments

207