Health Care

Distant doctors

caption

Kristy and Wes Fuller pose for a picture with son Karver (left) and daughter Farryn (right).When you live in Northern B.C., access complex pediatric care can mean travelling hundreds of kilometres south to Vancouver

Editor's Note

This story, originally published in print and online in the Prince George Citizen, was written and reported by Colin Slark as his professional project in the King's MJ program.

Kristy and Wes Fuller are sitting in a room in a clinic in Prince George, B.C. They’re with their son Karver. A nurse comes in to administer Karver his latest scheduled vaccination. The nurse takes a look at Karver’s file and turns to look at the Fullers.

“Are you guys the double-whammy family?” she asks.

The Fullers never thought their son’s story would become gossip, but a nurse they’d never met before has apparently heard all about the most difficult month of their lives.

“Didn’t you guys find out that your son needed open-heart surgery and had Down syndrome in like, the same day?”

The nurse isn’t far off track.

On Dec. 8, 2016, Kristy and Wes found out that their then-11-month-old boy had Down syndrome. On Dec. 12, they found out that Karver needed open-heart surgery. On Dec. 14, Karver spent six-and-a-half hours getting a congenital heart defect repaired.

Since Prince George lacks specialized pediatric care, the Fullers had to drive their son nine hours to receive treatment in British Columbia’s only pediatric hospital: Vancouver’s BC Children’s Hospital. Like all parents in B.C. that don’t live in Metro Vancouver, they had to take time off from work and pay for lodging, transportation and many other costs, while not receiving income.

Kristy and Wes spent over $10,000 to be with Karver during his time in hospital. This is the reality for parents of critically ill children in Northern B.C.

Karver’s story

Prince George is an industrial city of more than 70,000 people, close to the geographical centre of British Columbia. Most of the city lies on a plateau with some neighbourhoods on the surrounding hills. The major industry is forestry. The pungent smell given off by the pulp mills is known to some as “the smell of money” and to others as a reason to avoid the outdoors on a bad day.

The signs at the city limits describe the city as “B.C.’s Northern Capital.” To get to a larger community takes a five-hour drive. Major cities, Calgary, Edmonton and Vancouver, are all eight to nine hours away by car. This distance makes Prince George the de-facto major centre of the North.

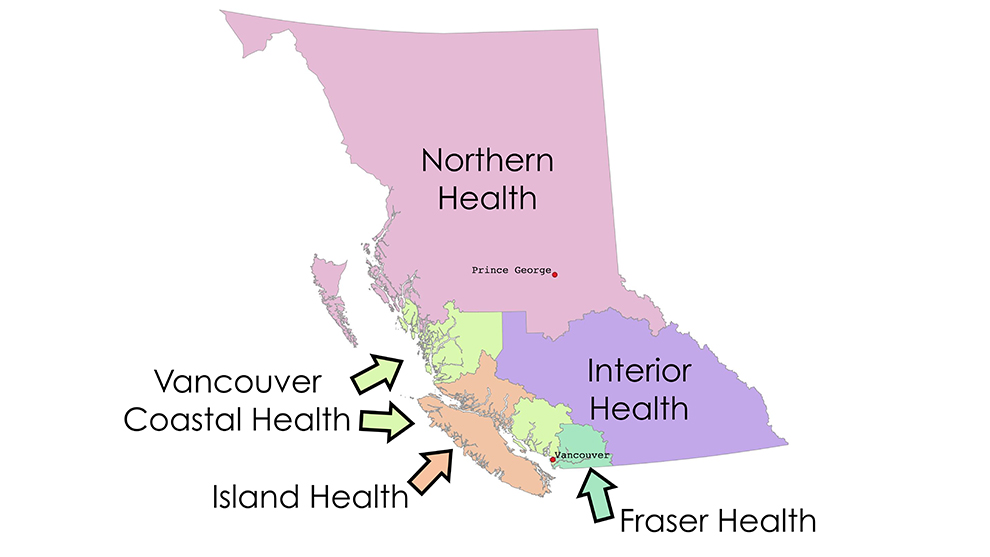

caption

British Columbia is divided geographically into five health authorities. A sixth manages specialty services across the whole province, such as those provided by the BC Children’s HospitalKristy and Wes Fuller live in a rural neighbourhood on the outskirts of Prince George. Kristy is a gregarious alpha mom who runs a massage therapy business out of their house. Wes is a quiet, reserved helicopter mechanic who is frequently away for weeks at a time for work, sometimes on other continents.

They needed help to get pregnant. Kristy’s ovaries were fine, but her Fallopian tubes were twisted and unhealthy. The Fullers travelled to Calgary to receive an in-vitro fertilization treatment.

As part of the treatment, the viable embryos received genetic testing for various conditions. However, Karver’s Down syndrome was not detected by the clinic. This is because Karver has a rare form called Mosaic Down syndrome, in which not every cell has the extra 21st chromosome that causes the condition. The sampled material simply may not have contained Down syndrome markers.

Prenatal ultrasounds back in Prince George also missed signs of Down syndrome, including Karver’s heart. Children with Down syndrome are more prone to congenital heart defects. Karver’s went undetected until he was 11 months old.

Karver was a sickly child. His parents covered his carrier to prevent him from catching any illnesses. Kristy took him to the swimming pool, but his skin turned blue unless he was in the hot tub.

“He always sounded pug-like. He always had really loud breathing, kind of wet sounding,” Kristy recalls.

In late November 2016, Kristy took a sick Karver to a walk-in clinic. The doctor looked at him and said, “Well, you know, kids with Down syndrome tend to get sick more often.”

This was news to Kristy. This was the first time she or Wes had considered that Karver might have the condition, but it made a certain sense. There were times where at the right angle she thought she recognized something in Karver’s face, but she couldn’t quite place it. This might have been because Mosaic Down syndrome doesn’t always present itself quite as obviously in a person’s facial features.

On Thursday, Dec. 8, 2016, a pediatrician confirmed to the parents that Karver has Down syndrome. Kristy recalls that at that doctor’s appointment, the pediatrician listened to Karver’s heart and tried to suppress a look of concern.

The Fullers were asked to take Karver for an electrocardiogram (ECG) at a laboratory in the same medical building before they left. Wes remembers taking the test results back up to the doctor’s office and the doctor snatched the paper right out of his hands.

At 5 p.m. that night, the family received a phone call from the pediatrician. He asked if they could make an appointment at BC Children’s Hospital in Vancouver on Monday. The Fullers weren’t given specifics, so they assumed that the doctors at the hospital just wanted to make sure that Karver would be well enough to fly to Mexico on a two-week post-Christmas vacation they’d booked.

Not realizing the severity of the situation, they packed lightly and thought they’d be away from home only briefly. Kristy put her massage therapy business on hold and Wes took leave from his mechanic work.

The first obstacle came on the trip south. The winter weather was so rough that it took them 14-and-a-half hours to make what is usually a nine-hour trip. The roads in B.C.’s Fraser Canyon were so bad that officials closed them just as the family made it out of the south end.

They were able to stay at Ronald McDonald House and Easter Seals House for parts of their stay in Vancouver. Both organizations provide subsidized housing in Vancouver for families of children coming to the Lower Mainland area to receive medical treatment.

However, while they were staying at Ronald McDonald House, Wes had to rent a hotel room elsewhere because he had a cold, as the institution doesn’t allow guests with communicable illnesses.

The next day, the Fullers went to BC Children’s Hospital and found out just how bad Karver’s situation was. Karver had a complete atrioventricular septal defect (AVSD). Normally a heart has four chambers. Karver’s heart hadn’t developed properly and only had two chambers.

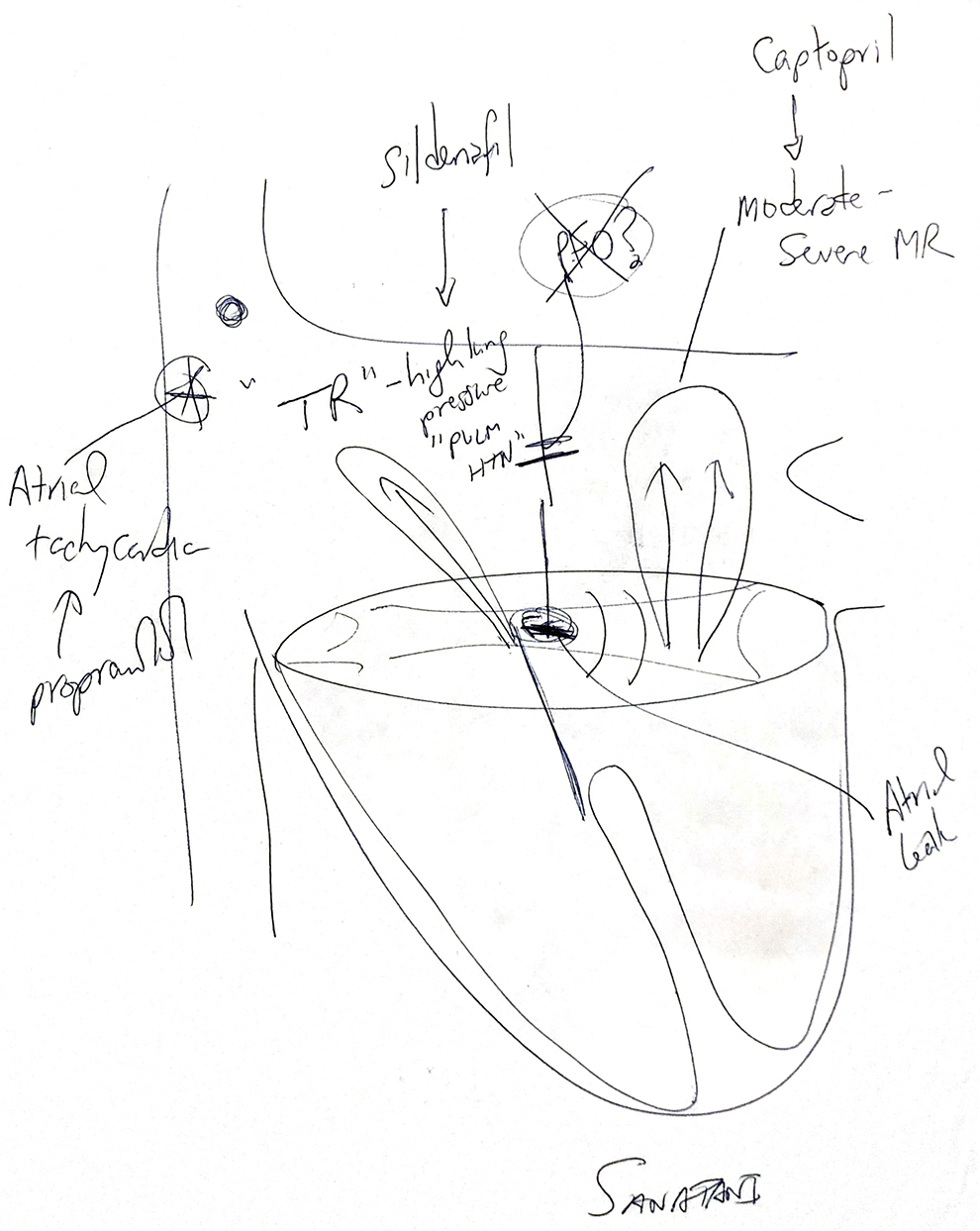

caption

This illustration of Karver’s heart before surgery was given to the Fullers by the heart surgeon.Two days later, Karver went in for surgery. The surgeons had to essentially redesign his heart. Complicating things was that Karver was much older than most children that get surgery for AVSD because the defect was discovered so late. Doctors told his parents the surgery would take four hours. It took six-and-a-half.

While Karver was in surgery, Kristy occupied herself by going to a Service Canada outlet and applying for Employment Insurance Family Caregiver benefits so that the family could receive some income while they were off work. Their initial application was denied until the surgeon that performed Karver’s surgery intervened and wrote a letter on Kristy’s behalf. They were approved afterwards.

Kristy says that the first time they tried to remove Karver from the bypass machine after the surgery, “it was like a sprinkler. The patches went and it just, like … blood went everywhere.” Doctors had to redo the patches on Karver’s heart.

Medical staff told the Fullers Karver would only need to spend 24 hours in the pediatric intensive care unit (PICU). That was on Dec. 14. Karver was moved out of the PICU 11 days later – on Christmas Day. Unfortunately, Karver’s stay was extended because he contracted Human Metapneumovirus and needed treatment for that. He was in the hospital for 10 more days after leaving the PICU.

What the Fullers had thought would be a quick trip ended up lasting more than three weeks.

Out-of-town healthcare costs

Costs add up quickly when travelling out of town to get medical treatment for a sick child.

In Northern B.C., the distances are vast. Prince George isn’t actually in the geographical northern half of the province, but it is considered part of “northern” B.C. The Fullers had to travel around 800 kilometres to get to BC Children’s Hospital. The distances only go up for residents of more remote northern communities.

Imagine taking a current model Honda Civic automatic sedan on that 800-kilometre drive. Honda lists the highway fuel economy at 6.1 litres used for every 100 kilometres travelled. The car would use around 48.8 litres of fuel on the road from Prince George to Vancouver. In December 2016, the average Canadian fuel price was 101.6 cents per litre. That’s almost $50 in gas for a one-way trip in a small car. That doesn’t count gas used travelling at the destination city or for the return trip.

There are some services available to help people without vehicles travel for medical appointments, but the situation has been complicated by Greyhound ending services in Western Canada in 2018. The provincial government has created a new service called BC Bus North to replace some of Greyhound’s routes, but it only connects communities in Northern B.C.

caption

A Northern Health Connections bus waits for passengers at Prince George’s Parkwood Mall.Health care in British Columbia is managed by health authorities that are responsible for different geographical regions. Northern B.C.’s health authority, Northern Health, runs a bus service called NH Connections from Prince George to Vancouver three times a week in both directions. One-way trips cost between $20 and $40 depending on where you board the bus. Upon request, NH Connections will give out letters confirming medical care in the Vancouver area for hotels that offer medical rates.

Interior Health (Kamloops, Kelowna), Island Health (Vancouver Island) and Vancouver Coastal Health (Bella Coola and Central Coast) also offer their own “Connections” services, but their routes only travel within their health authorities’ own boundaries.

A Canadian charity called Hope Air helps some patients afford air travel for medical care. Families that demonstrate financial need and can provide proof of an out-of-town health care appointment can apply to the charity for assistance. If accepted, Hope Air will pay for round-trip tickets on a commercial airline for a patient and an escort if the patient is 18 or younger. However, Hope Air does not pay extra fees for such things as checked luggage or in-flight meals.

Otherwise, a one-way ticket from Prince George to Vancouver can cost around $500 per person before fees and taxes, if booked on short notice. If patients have the luxury of booking months in advance, tickets can still cost around $150 before fees and taxes.

The provincial government does run a Travel Assistance Program (TAP B.C.). Patients receiving non-emergency specialist services at the closest location outside of their home community and patients receiving specialist care are eligible for benefits under this program, so long as they have a referral and their travel expenses are not covered by third-party insurance.

An escort is allowed for patients who are either 18 years old or younger or incapable of travelling alone. Claims for assistance cannot be filed retroactively for TAP B.C.

Housing is expensive too. NH Connections maintains a list of hotels with medical rates. A Sandman Hotel in Vancouver city centre charges $129 for a room with two doubles from May to September and $89 the rest of the year. On Expedia.ca, booking the same kind of room at that hotel costs $169 a night without the medical rate. If you had requested the same room for December 2019, it would have set you back $175.

The sickest kids

Lucky families who get a room at Ronald McDonald House only have to pay $12 a night and the facility is on the grounds of BC Children’s Hospital. Ronald McDonald House has 73 rooms of different sizes with private bathrooms and access to communal kitchens and dining areas, as well as entertainment facilities. To apply to stay at Ronald McDonald House, families must prove that they have a medical appointment at BC Children’s Hospital and have travelled farther than 50 kilometres to receive medical care. There is usually a waiting list to get in.

“Our priority system is essentially the sickest children from the farthest away,” says Shannon Kidd, vice-president of external relations for Ronald McDonald House of B.C. and Yukon. Kidd says if families cannot afford the $12 a day fee, the facility does not pressure them to pay.

A similar facility is Easter Seals House. They’re located a few blocks away from BC Children’s Hospital and have 49 suites with access to laundry facilities, lounges and in-suite kitchenettes. Easter Seals House charges $40 a night for a single guest and $25 a night for a second guest.

Residents of B.C. can apply for the provincial government’s B.C. Family Residence Program, which is run by the charity Variety. Families that have a child receiving medical care at BC Children’s Hospital or the Sunny Hill Health Centre for Children and live outside Metro Vancouver (excluding Bowen Island and other island communities) are eligible to have accommodation costs paid directly to the facility they’re staying at for up to 30 days per medical visit. This program does not cover transportation costs, meals, or other personal expenses.

Variety also offers assistance to parents and caregivers away from their home community to seek medical attention for a child through their “Variety Cares Fund.”

The Fullers were lucky in that they had a friend offer to pay for their hotel stay when they weren’t able to be at Ronald McDonald House. Some of their friends in Prince George also ran a fundraiser to help them cover the cost of being away from home.

The EI Family Caregiver Benefit grants up to 55 per cent of a parent’s average weekly insurable earnings (to a maximum of $562 a week) if accepted. The parent needs to have accumulated 600 hours of insurable employment in the 52 weeks preceding the claim or since the beginning of the last claim, whichever is shorter.

While the provincial government offers these programs to help parents who have travelled to Vancouver to get their kids health care, nobody told the Fullers.

Kristy and Wes were able to apply for the B.C. Family Residency Program, but only after they were made aware of its existence when a staff member at Easter Seals House asked them if they had signed up.

Pediatric healthcare in Northern B.C.

caption

The University Hospital of Northern British Columbia in Prince George is Northern B.C.’s largest hospitalThe University Hospital of Northern British Columbia (UHNBC) in Prince George is the largest hospital in Northern B.C. With specialized services including a cancer clinic and a teaching partnership with the University of Northern British Columbia, patients from around the region come to Prince George for care when their local facilities can’t handle their needs.

However, UHNBC does not have a large pediatric department. In Northern B.C., there are six pediatricians in Prince George, three in Terrace, one in Prince Rupert and one in Fort St. John. That’s it. While UHNBC can handle generalized care and some emergency situations, anything else needs to be handled at BC Children’s Hospital.

“Anything that requires a specialized pediatrician like cardiology, gastroenterology, you name it, immunology, rheumatology, it’s all in Vancouver,” says Dr. Kirsten Miller, the medical lead for Northern Health’s Child and Youth Health Program. “It would be hard to answer [the question] of what services kids go to Vancouver for. It might be easier to say what services they don’t go for.”

According to Miller, geography is the biggest challenge in providing pediatric health care in Northern B.C. “We see kids that live hours and hours from a pediatrician,” she says. “I just got a phone call about a kid that’s having trouble breathing in Takla, which is by land going to take five or six hours to get here.”

If there was a child needing specialized pediatric health care in say, Yarmouth, Nova Scotia, it would be a three-hour drive one way to get treatment at the IWK Health Centre in Halifax. For a family in Prince George, it’s a nine-hour drive to Vancouver to get treatment at BC Children’s Hospital. For a family in Terrace, B.C. it’s a 15-hour drive to Vancouver, and 18-and-a-half hours for a family in Fort Nelson, B.C.

Some families in northeastern B.C. choose to take their children to Grande Prairie or Edmonton in Alberta for non-urgent medical appointments because the distances involved make those locations easier to access. A patient in Fort Nelson would only need to drive 11 hours to Edmonton versus 18-and-a-half hours to Vancouver.

Miller says a couple of things would make her job easier as a pediatrician in the North. One would be a provincial-based approach to pediatric care that includes telemedicine appointments for hard-to-reach communities. Another would be the improvement of transportation services for critically ill children.

“I had two children come in this (February) long weekend from smaller communities in our region and they both had to come by land ambulance in the black of night, on icy roads, with basic ambulance crews that in my opinion probably couldn’t have managed any complications that would’ve arisen on the way,” Miller says. “There needs to be more money for flying kids with a specialized infant transport team than there currently is.”

While the bulk of patients treated at BC Children’s Hospital are from the Metro Vancouver area, patients from other regions of B.C. make up a substantial amount of their caseload. In the 2016/17 fiscal year, 458 cases treated at BC Children’s Hospital were patients from Northern B.C. and 279 of those cases were patients from Prince George. In 2017/18, 386 cases were from Northern B.C., with 237 of those being from Prince George.

Other regions in B.C. are closer to Metro Vancouver and they make up thousands of other cases every year. Care at BC Children’s Hospital still means driving hours away from home, taking ferries or flights, and hundreds if not thousands of dollars in expenses.

Next up for Karver

After his heart surgery, Karver has thrived. While his speech lags behind children without Down syndrome, he gives confident one-word answers to questions.

The speech therapist at Prince George’s Child Development Centre is only able to see Karver once a month or less, so Kristy supplements his learning with a computer program that helps him learn new words.

Karver loves to play. He has a wooden train track built in his play area at home. He surrounds it with plastic skyscrapers topped with Lego figures.

caption

Kristy and Wes had trouble finding Karver a daycare that would allow Karver to have an aide.When Wes is home from work, Karver plays outside with him and the family dogs. One of the dogs’ names, Memphis, is one of Karver’s favourite words.

Initially, the family had a hard time finding Karver a daycare that would allow him to have a staff member dedicated to helping him. In the beginning, they hired a nanny to take care of Karver while Kristy was working. Now Karver has got into a facility that allows him to have a personal aide and he’s loving the chance to socialize with other kids.

Recently, Karver became a big brother. Kristy and Wes welcomed daughter Farryn to the world in early 2019. While Karver is sometimes jealous that his sister is getting lots of attention, he clearly loves her.

Karver shows affection by giving out fist bumps and is already trying to teach his infant sister how to do them.

Karver’s medical team has been hesitant to do any more work on his heart for fear that any surgeries might make matters worse. But Karver’s heart has been prone to mitral valve regurgitation, where the heart’s mitral valve doesn’t close tightly enough. This allows blood to travel backwards in the heart, impeding circulation.

The problem has progressed to the point where Karver will need to have another open heart surgery next month (August). It won’t be as complex as the surgery that reshaped his heart but it will require Kristy and Wes to take more time off work. However, family friends have recently put on a fundraiser to help the family with the costs of being away from home.

Karver is expected to only be in hospital five days but will need to stay in the Vancouver area for monitoring for another week. Kristy always knew that Karver would need more work done but had hoped for more time between procedures.

“We really thought we had years before they were going to do a surgery, not a couple of months,” Kristy said.

While the thought of another open heart surgery is scary, Kristy and Wes know that they’ve survived worse. Both parents have tattoos of the ECG of Karver’s heart after he went through his first surgery to remind themselves of what they’ve overcome.

caption

Both parents have tattoos to commemorate what they and their son have overcome.Kristy and Wes have seen Karver’s potential in the years since his first health crisis and are doing everything they can to keep their son on that path.