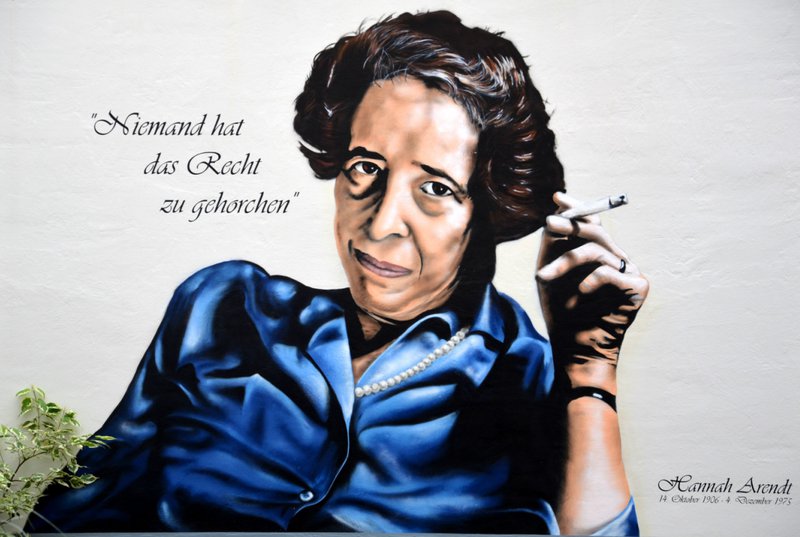

Mural of Hannah Arendt in Hanover. Credit: Wikipedia by graffitos BeneR1 and koarts, based on a photograph by Käthe Fürst. Public Domain.

In Hannah Arendt’s Denktagebuch (or ‘Thinking journal’) there’s a short entry on “Amor mundi — warum ist es so schwer, die Welt zu lieben?” “Love of the world — why is it so difficult to love the world?”

The day after the 2016 US presidential election I wrote a small piece for the Hannah Arendt Center newsletter Amor Mundi. Caught in the throes of grief, shocked, and uncertain of the future, I said that now we had to learn to love the world. Arendt’s provocation in that moment gave me a sense of calm and purpose, something to hold on to.

In moments of distress we often turn to poets and poetic thinkers to provide a sense of place and solace. W.H. Auden, Bertolt Brecht, Hannah Arendt. It’s not a coincidence that George Orwell and Arendt are selling in record numbers right now, 16 per cent above the usual rate. Publishers are running new prints of The Origins of Totalitarianism and even Theodor Adorno’s epic work The Authoritarian Personality. We’re at a cultural moment where we’re looking for understanding.

Readers looking to Arendt’s Amor Mundi for a form of political love might at first be disappointed. Amor Mundi—love of the world—is not love in any sense we’re commonly used to. There is, however, a challenge to think about what it means to be committed to the world, to care for the world despite its horrors. There is a provocation to embrace one another in our difference and to meet one another as fellow human beings. There is also a radical critique to be found of more common forms of love, which are destructive of difference and plurality.

Arendt’s conception of Amor Mundi has more to do with understanding and critical thinking than with sentiment or affect. For her, love cannot be political. It is dangerous and destructive to the realm of political affairs. Throughout her work, Arendt discusses numerous forms of love: eros, philia, agape, cupiditus, caritas, fraternitas. But love and politics is dangerous terrain.

In her treatise on The Human Condition, which she intended to title Amor Mundi, she writes:

“Love, by its very nature, is unworldly, and it is for this reason rather than its rarity that it is not only apolitical but antipolitical, perhaps the most powerful of all antipolitical forces.”

Love of the world is also not the same as equality or care, or extending oneself to another from a place of need. In a letter to Auden Arendt chastises his characterization of charity and forgiveness as a form of love, writing that:

“You talk about charity as though it were love, and it is true that love will forgive everything because of its utter commitment to the beloved person. But even love violates the integrity of the wrongdoer if it forgives without having been asked to.”

Love in this sense is not the same as forgiveness, because love is not capable of critical thinking and judgment—it 'violates the integrity of the wrongdoer,' flattening all wrongs to a plane where each can be forgiven. In another letter to James Baldwin Arendt also criticizes his understanding of political love:

“What frightened me in your essay was the gospel of love which you begin to preach at the end. In politics, love is a stranger, and when it intrudes upon it nothing is being achieved except hypocrisy. All the characteristics you stress in the Negro people: their beauty, their capacity for joy, their warmth, and their humanity, are well-known characteristics of all oppressed people. They grow out of suffering and they are the proudest possession of all pariahs. Unfortunately, they have never survived the hour of liberation by even five minutes. Hatred and love belong together, and they are both destructive; you can afford them only in private and, as a people, only so long as you are not free.”

The love that belongs to the oppressed makes the injustices they suffer bearable. And when this love, with its empathy and commitments to justice and equality, enters the public realm it becomes destructive of plurality, which is the foundation of democracy. For Arendt there is a distinction between solidarity, which is the acceptance of difference and welcoming of plurality, and empathy and equality, which seek to flatten and condense. Baldwin’s idea of love can only ever threaten the political by leading us away from democracy.

Love of the world is about understanding and reconciling one’s self with the world as it is. Or, to use Arendt’s own language, it is the idea that we must “face and come to terms with what really happened”, and what is happening today. How can we live in a world where something like the Holocaust is possible? In her letter to Karl Jaspers written on August 6, 1955, Arendt says:

“Yes, I would like to bring the wide world to you this time. I’ve begun so late, really only in recent years, to truly love the world that I shall be able to do that now. Out of gratitude, I want to call my book on political theory ‘Amor Mundi.’”

This passage comes in the middle of the letter, where Arendt is describing the “melancholy task” she’s been working on—writing introductions for books by two deceased friends, Hermann Broch and Waldemar Gurian. It is only because of her love of the world that she is able to perform this one last act of friendship. Within this statement there is a recognition and reckoning with the events of the past. What does it mean to love the world in face of such great loss?

For Arendt, Amor Mundi is bound up with her axiom at the beginning of The Human Condition that we must stop and think what we are doing, along with the idea of reconciliation that is threaded throughout her thinking journal and her essays on responsibility and judgment. There is a form of self-reflective critical thinking contained within these ideas, since in order to see the world as it is we must stand on the sidelines, find perspective, and a place of solitude for thinking. In other words, there has to be a turning in before we can turn out. Loving the world requires reckoning with the world, which means we must find some critical distance from what is happening around us. When we witness injustices, sometimes there is an impulse to act, but Arendt cautions us to slow down and think what we are doing—to be thinkers not just joiners.

This form of reckoning and reconciliation might also be understood as making peace with one’s self; finding a way to have fidelity to one’s thoughts even in our darkest moments of loss, grief, and crisis. Amor Mundi can give us a metaphysical sense of certainty in a world that is always being destroyed. It is a relational form of love.

In earlier letters to Jaspers Arendt talks about the joy she finds in the American people—a young fishmonger who has read all of Jaspers’ work, a young girl from a poor family whose living room is filled with books of Plato, Hegel, and Kant. Loving the world involves reconciling ourselves with the events of the past so that we can move about the everydayness of life, to go on living, to create, to find joy, to find perspective, to build new friendships, and to remind ourselves of where the possible remains—in language, in poems, in the young fishmonger who has a fondness for philosophy. It’s a promise of continued existence, a way of not resigning from the world when the world seems too unbearable to live in.

What kind of world are we facing today? Why is public funding being allocated to walls instead of arts? Why are so many Americans unable to afford health insurance? Why do we value some lives more than others? And why are middle-aged Americans committing suicide at unprecedented rates?

More broadly, how is there genocide in the 21st century? Why are we experiencing the largest refugee crisis since the Second World War? Why do we keep insisting on the rhetoric of social equality instead of learning to appreciate and celebrate our differences? And why do we demand answers to any of these questions when the logic of question-answer is the same logic of tyrannical thinking?

Arendt’s conception of Amor Mundi is not comforting, it is challenging. It refuses the idea that we can ‘find meaning in’ or ‘make sense of’ and instead pushes us to work hard to understand and accept that there are no answers to these questions in the way we might wish.

In teaching us to love the world Arendt is teaching us to be thinking, engaged citizens. She cautions us against the impulses of sentiment or affect, and guides us toward political thinking. Loving the world offers us a way of being in the world that plants our feet firmly in reality, so that we can see what is before us.

Read more

Get our weekly email

Comments

We encourage anyone to comment, please consult the oD commenting guidelines if you have any questions.