Six epic translation fails

Translating an idea clearly from one language to another can be notoriously tricky. To mark Short Cuts: Lost in Translation, which explores the complexities of talking in a new tongue, we look at six translations that went seriously wrong – from amusing errors to major mistakes.

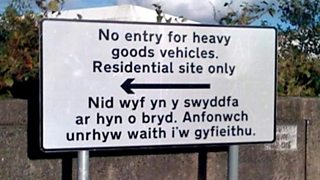

1. Misdirection in Wales

With more than 300,000 fluent Welsh speakers in the UK, you might not think translations could go far wrong. But in 2012, Welsh drivers in the Vale of Glamorgan were instructed to “follow the entertainment” instead of taking an alternative route, thanks to an inaccurate translation of “diversion”.

And, in 2008, sign designers at Swansea Council didn’t realise they had received an automated response in Welsh, rather than a super speedy translation. As a result, a road sign went up featuring a translator’s out-of-office email reply.

2. The mistake that created an alien civilisation

At the end of the 19th Century, a tiny error in translation led to the mistaken belief that there were alien civilisations living on Mars. It all started when Italian astronomer Giovanni Schiaparelli began mapping the Red Planet, and labelled grooves on its surface as “canali”, meaning “channels” in Italian. But, with the recently completed Suez Canal high in people’s minds, an over-eager reader simply read it as “canal”. Soon, people began to believe that intelligent beings were present on Mars and accomplishing their own great feats of alien engineering.

The American Percival Lowell devoted much of his life to studying the planet and painstakingly mapping out hundreds of lines on its surface. He claimed that these “canals” were designed by Martians to transport water from the poles to the equator. Lowell’s books are even said to have caught the attention of the writer HG Wells, helping to inspire his science fiction classic, The War of the Worlds.

Today though, astronomers don’t believe any of these channels even exist – let alone alien-built canals. NASA says the lines are an optical illusion produced by our habit of looking for patterns among random shapes.

3. Google’s algorithm gets creative

In 2016, Google had to make a quick fix after a bug in its automated online translation system created some confusing results for people trying to convert Ukrainian into Russian.

Users noticed that “Russian Federation” was being translated as “Mordor”, the name of the dark kingdom in JRR Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings. The errors didn’t stop there: “Russians” came out as “occupiers” and the name of the country’s foreign minister, Sergey Lavrov, was translated to “sad little horse”.

Google described the mistakes as a “technical error”, and said its translation software arrived at its results by scanning hundreds of millions of online sources, which meant there were occasionally errors. Journalists observed that the language reflected terms adopted by some Ukrainians after Russia annexed Crimea in 2014.

4. Banking slogan translates to inaction

For multinational brands, finding words that translate worldwide can be a costly endeavour. HSBC discovered this when its “Assume nothing” slogan was converted to “Do nothing” in several countries. Soon after, the company rebranded its entire global private banking operation at a cost of $10 million, settling instead on the more translatable slogan: “The world’s private bank”.

5. President or doughnut?

In one of President John F. Kennedy’s most famous speeches, he may have accidentally announced that he was a jam doughnut. In 1963, the US leader told a crowd in Germany, “Ich bin ein Berliner” in an expression of solidarity with the people of West Berlin.

However, linguists have since pointed out that instead of describing himself as a citizen of Berlin, by adding “ein”, Kennedy had marked himself out as another kind of “berliner” – a type of jam doughnut.

But, others argue it’s all about context and that real Berliners would have known what he meant. After all, the president wasn’t speaking literally, making “ein” an acceptable addition. And anyway, in Berlin itself, jam doughnuts are more commonly called “pfannkuchen”.

6. An unintentional nuclear threat

During the Cold War, tensions intensified when communist leader Nikita Khrushchev was quoted as saying “we will bury you” at a reception for Western delegates in Moscow.

The apparent threat made headlines around the world and led people in the United States to fear an imminent nuclear assault. But Khrushchev later said he had been misinterpreted, explaining that he was describing how capitalism would fall and communism would outlast it – or see it buried.

-

![]()

Short Cuts: Lost in Translation

Secret languages, loving acts of translation and musical instruments with an unrecognised power – Josie Long presents documentaries about translation.

More from BBC Radio 4

-

![]()

Short Cuts podcast

Short documentaries and adventures in sound presented by Josie Long.

-

![]()

How to tell a story

Make a connection and include a twist. Watch Josie Long's guide to great storytelling.

-

![]()

Word of Mouth

Series exploring the world of words and the ways in which we use them

-

![]()

The road markings that left red faces

BBC News rounds up some of the gaffes that have hit the headlines.