Disney staff used to call it the morgue, a windowless bunker of a building near corporate headquarters which stored drawings and sketches dating back decades.

The very first pencilings of Mickey Mouse, drafts of the forest in Sleeping Beauty, underwater sequences in The Little Mermaid and millions of other scenes and fragments from films, all diligently stored in the building’s 11 vaults in Glendale, Los Angeles.

The lugubrious nickname conjured mildewed arcana, a forgotten department two miles from the Burbank studio where paper went to die. A deceptive impression.

The morgue, now officially called the Walt Disney Animation Research Library, channels a corporate life-force that has made Disney the world’s entertainment behemoth.

“For a long time this was known as Disney’s secret weapon because the company could always go back to reuse and develop material. Every single animated drawing has its own record. Amazing really because Hollywood is usually so ephemeral,” said Fox Carney, the library’s research manager.

He spoke while giving the Guardian and a handful of other media outlets a rare peek inside the library – a tour through a silent, temperature-controlled labyrinth that underlined Disney’s zealous protection of its past and huge ambitions for its future.

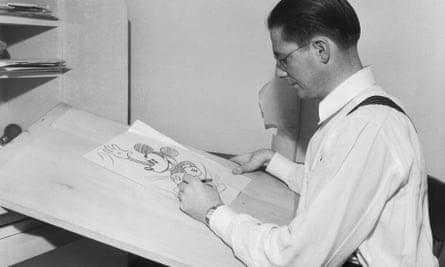

The visit was timed to celebrate the 90th birthday of Mickey Mouse, who debuted in the animated short Steamboat Willie in November 1928.

The squeaky-voiced rodent has since spawned a $95bn empire that encompasses classic characters such as Peter Pan and Winnie the Pooh, Pixar cartoons, Marvel blockbusters, Star Wars reboots, theme parks, cruise ships, comics, books, computer games, toys, T-shirts and other merchandising. Disney is poised to swell even bigger under a proposed $71bn deal for most of 21st Century Fox.

“Walt liked to say it all started with a mouse,” said Rebecca Cline, director of the Walt Disney archives, which are based in the Burbank headquarters. “Mickey Mouse is the rock on which the company was built.”

Some in Hollywood still refer to Disney as the House of Mouse but the company archives showcase its real key to world domination: intellectual property (IP).

At the animation research library, staffed by 24 people, the company is methodically storing, curating and digitising an Aladdin’s cave of animation models and drawings – 65m items – in recognition that these characters and stories represent corporate treasure.

Items include moulds that artists used to draw the orchestra figures in Fantasia, landscapes from Snow White and the original Pinocchio puppet, who lies in a glass case, preserved in perpetuity, the Lenin of Burbank.

The digitising shows long-term horizons: the painstaking process of photographing and capturing pieces of art will take an estimated 120 years – perhaps finishing in time for Mickey’s 210th birthday.

“We started nine years ago,” said Mat Fretschel, one of the archival photographers. “On a good day we photograph about a thousand pieces of art. We’ve done about 1.1% of the archive.”

Some sketches showed what artists had erased and amended, providing invaluable insights into their thought processes, said Carney.

Artists working on current projects can access the digitised material online or visit the archive to study originals. The team that worked on Zootopia (2016) studied sketches from Robin Hood (1973) for tips on depicting animals that walk on two legs. The trove also helped artists unify princesses from multiple stories in a trailer for the upcoming Wreck-It Ralph sequel.

Even material from abandoned or unreleased projects is stored and digitised, a policy that allowed the team behind The Little Mermaid (1989) to study iterations from the 1950s.

Film scholars and lovers of Disney films can only cheer such dedication. There is a flip side. In protecting copyright and trademarks, the corporation exudes a sharp vigilance worthy of Captain Hook. Any unauthorised depiction of Mickey Mouse, Obi-Wan Kenobi, Iron Man, Mary Poppins or any other character under the Disney umbrella, be it for profit, satire or fun, tends to get swiftly stomped on.

“No T-shirt vendor is too small that their lawyers don’t crack down with cease-and-desist letters,” said Richard Rushfield, who publishes an entertainment industry newsletter, the Ankler.

Jesse Lerner, a Pitzer college professor who co-curated a Los Angeles exhibition on Disney’s relationship with Latin America, agreed. “Disney is very aggressive in protecting their intellectual property.”

The company waged a long-running battle to try to pocket more royalties from Winnie the Pooh, worth about a $1bn a year, which had been shared with a Beverly Hills family.

Disney’s lobbying power is widely perceived in the US’s 1998 Copyright Term Extension Act, which has been dubbed the Mickey Mouse Protection Act. It delays when works of art become public domain. Mickey remains shielded until 2024 – or later, if the law is changed again.

It’s not just the mouse, Goofy, Donald Duck and other characters conjured by Walt Disney. Under Bob Iger, who became Disney’s CEO in 2005, Disney has been on an epic buying spree, snapping up Marvel (and thus Thor, Incredible Hulk, Captain America, X-Men, Guardians of the Galaxy) for $4.2bn in 2009 and Lucasfilm (and thus Star Wars) for $4bn in 2012.

The strategy of paying fortunes to create giant brands to recycle in films and merchandise has paid off, said Rushfield. “It’s just staggering the number of different characters they have. For a modern media company that’s the real estate that you’re sitting on.” Rushfield has nicknamed Iger “IP Bob”.

The company’s focus on IP sprouts from its own corporate origin story.

In 1927 a young Walt Disney and his chief animator, Ub Iwerks, created an animated character, Oswald the Lucky Rabbit, for Universal studios. In a dispute with the distributor Disney lost control of the rabbit. Dejected and worried, according to lore, on a train journey home he dreamed up a particular mouse – and resolved to keep the rights.

“It’s not just brand recognition. Mickey is intrinsically appealing to children,” said Cline, the archive director. “Mickey is an everyman. He’s been a tailor, a cowboy, a plumber, a farmer. You can send him anywhere in the world or outer space or underwater – we’ll never run out of stories.”

Or lawyers, as many of those who have tried using the mouse’s image can attest.

A bronze statue at company headquarters depicts Mickey and his creator holding hands. An apt image. Disney never let go.