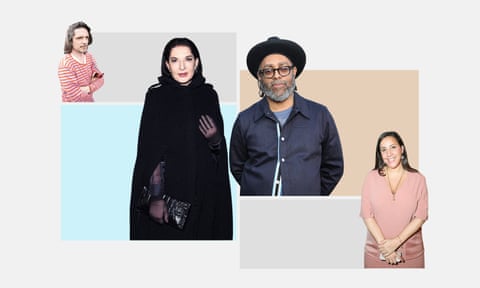

Tacita Dean

Artist

I think the biggest problem for artists is balancing a need for the market with a detachment from it. The demise of public funding and the overbearing existence of large, commerce-oriented galleries that even museums rely on these days, has distorted the capacity of artists to work freely. We are increasingly mollified by commercial obedience. There needs to be plurality again: other ways, more confusion, fewer defined routes.

Rivane Neuenschwander

Artist

Recently, artists and cultural institutions in Brazil have been censored and subject to attacks by ultra-conservative groups and politicians. This is both very serious and dangerous, putting our already fragile democracy at risk. We are experiencing a period of profound social inequality, times of intolerance and polarisation worldwide, where the discourse of fear and hatred has rapidly dominated and impoverished discussions.

The artist must resist and point out diversified paths of deeper reflections, defending their field of action in order to guarantee a place for experimentation and freedom for all within society.

Stefan Kalmár

Director of the ICA

The big question for us all – but particularly for artists because it’s more pressing – is, essentially, can we bite the hand that feeds us? The economic make-up of the 21st century has forced us to shy away from more fundamental questions. An artist is now someone who sells work through a commercial system, to people they might not know, whose political and social affiliations they might not know. As a director, you wonder how long those contradictions are sustainable. Your exhibition might be sponsored by people who you oppose.

How many galleries in the US have Trump supporters as their major donors? How does that sit with the more progressive curatorial decisions? Equally, how does the ICA behave with those contradictions? I mean, at least we can talk about them, rather than pretending they’re not there.

Then there is the question of education in general, and art education in particular. Why is it that a society that largely communicates through visual media then deprives generations of young people of an arts education? To do so essentially produces a visual illiteracy, so people can’t understand or read the world. They cannot understand that the world projected at them has social, economic preconditions and interests behind them. In a world that is saturated by image, where ideologies talk to each other through imagery, it is a basic human right to understand how images are produced, circulated and distributed. It’s like learning a language or learning the alphabet. Isn’t looking after the people the basic foundation of any politics? Why would it ever be interesting to introduce tuition fees and reduce people’s access to education? The same for healthcare. Why should it be difficult? Shouldn’t it always be government’s prime mandate to produce a well-educated and healthy society? We could get more political and say, “Why is it always conservative governments that do this?” There isn’t a liberal or social democratic element that would do that. You very, very rarely get well-educated fascists or racists.

Jeremy Deller

Artist

“WTF?” That’s the question facing artists today.

Marina Abramović

Artist

For me, it is the question of morality. I think it’s not enough for artists to make work, and to show that to the public. We also have to see ourselves as human beings; to ask what can we do in the world, which is really in the biggest crisis it has ever been in. As a human being, how can you help on a human level? It’s a crisis in every possible form. Human beings suffer everywhere in the world. It’s the increasing natural disasters, which have never been so frequent; hunger; the movement of large populations of people; the people who run the government. Just doing art, being in the studio, is not enough. You have to think about what you can do as a human being.

Artist Talks: Marina Abramović is presented by Fondation Beyeler and UBS and will be livestreamed on 4 October at 7pm on Facebook.

Maria Balshaw

Director of the Tate

Where can I afford to live and make my work? Where is my creative community?

Arthur Jafa

Artist and film-maker

In the bluntest terms, the thing that seems to be true of most artists is: “How do I get paid?” You have better odds of becoming a successful NBA player than you do of becoming a successful artist.

What I’m preoccupied with is creating things that feel like a real embodiment of everything that makes me who I am. And that is completely bound up with everything that makes me black. As soon as I say I’m black, I’m constrained. On one hand I assert that I’m black because I’m about dealing, but on the other hand I don’t want other people to impose any kind of narrow limits on what black might be. It puts me in a position where I often feel somewhat contrary because I just don’t want to be boxed. I just want to be free to do what I want to do. If you take Love Is the Message, I found myself being disturbed that it is so often framed in sociopolitical, Black Lives Matter terms. Why don’t people ever talk about it in relation to Bernini’s Ecstasy of Saint Teresa? But at the same time, if people talk about it in formal terms, then I’m irate because they just want to talk about it in formal terms while black people are getting killed like dogs!

I aspire to complexity, nuance, beauty – those are the things that I value. They are also the things that are congenitally denied to me as a black person. I know, for example, that if I made Mark Leckey’s masterpiece, GreenScreenRefrigerator, it would be read in a completely different way. My reading of that piece is that it’s about the emotional life of objects, and historically, black people, when we came into life in the west, we were not people; we were things. So we have a really crazy, complicated relationship to the life of the thing. We’re situated somewhere between the subject and object.

Arthur Jafa’s Love Is the Message, the Message Is Death is co-presented by the Serpentine at Store Studios until 10 December.

Catherine Opie

Artist

My biggest concern is equality for women artists and affordable housing: the practicality of making a living and being a practising artist is daunting. Perseverance, my fellow artists! And be authentic with your practice.

In a world in which political upheaval seems to be at every turn, I think one of the larger questions is: what type of artist do I want to be? There is no right or wrong answer; it is important to know that the artist’s voice and work can span a larger discourse in relationship to contemporary culture, politics and practice.

Kim Yong-ik

Artist

The “surplus” of production and consumption has become an imposing threat to us. As an artist, I am not so keen on the idea of excessive production and circulation of the visual image.

Kim Yong-ik will exhibit at Spike Island, Bristol, and the Korean Cultural Centre UK. His work will be in the Kukje gallery booth at Frieze London.

Oreet Ashery

Artist

For me, there are a lot of questions around the ethics of funding and the politics of representation. Who are we representing, who are we taking pictures of or filming, what is the work about? I also have a lot of ecological concerns. I think for a lot of artists, trying to negotiate their position around funding and sponsorship is a minefield. If your work is around climate change, to work with or be sponsored by certain oil companies would be very weird. We can’t fight all the wars, but, if your practice has particular areas that it deals with, then the funding around that has to make sense. Saying that, I don’t think anyone should be working with money that comes from arms dealing.

A lot of responsibility is put on to artists rather than structures. There’s a lot more demand to find private funding but that can put artists in positions where they’re forced into corporate strategies. There’s quite a finger-pointing culture among artists. That pressure to say the right thing can distract from the battles we actually need to fight.

I have had to negotiate an identity around being queer, around being non-binary, from a working-class background, not having children, being single; all these things that in an institutional context are a lot more difficult. But for me, now, there are more categories for identity. It has a way to go but it feels like there is more official recognition for different types of identity, by those institutions. A lot of the young people I teach identify as non-binary and that has to be accounted for. The whole debate around identity is more subtle now. And, of course, that identity affects the kind of work you want to make.

Oreet is shortlisted for the 2017 Film London Jarman award announced 20 November.

Touria El Glaoui

Founding director of 1:54 Contemporary African art fair

It’s a question of security in your career: how to be true to yourself while surviving in a commercial market. There is pressure on artists to be activists, with a message to society, to think about how their work will influence certain political changes. So for them the question is: how can my work transmit some sort of social, political message? How will I fit into the future? In Africa, the market is still finding its ground, so the future has a bigger space and that affects the way artists think about their work. When I hear artists discussing their practice in Africa or as part of a diaspora, a lot of what they’re talking about is how to become part of a gallery or a particular show.

The 1:54 Contemporary African art fair is at Somerset House until 8 October.

- Interviews by Nell Frizzell. Frieze London takes place in Regent’s Park, until 8 October.