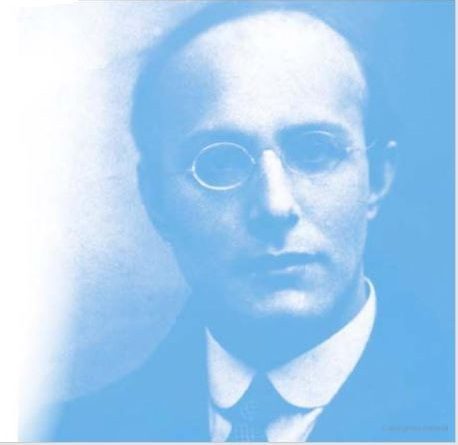

A brilliant and influential sociologist Neil Smelser passed away on Monday at the age of 87, leaving behind an extraordinary intellectual legacy. Among many contributions during his prolific academic career, unparalleled in its diversity and breadth (in social change, social movements, sociology of education, comparative history, sociological theory, etc) — UC Berkeley Professor Smelser has laid the foundations for the rebirth of Economic Sociology and steadily promoted it on the scholarly as well as organizational levels.

A brilliant and influential sociologist Neil Smelser passed away on Monday at the age of 87, leaving behind an extraordinary intellectual legacy. Among many contributions during his prolific academic career, unparalleled in its diversity and breadth (in social change, social movements, sociology of education, comparative history, sociological theory, etc) — UC Berkeley Professor Smelser has laid the foundations for the rebirth of Economic Sociology and steadily promoted it on the scholarly as well as organizational levels.

In 1956, during his first year at Harvard graduate school, Smelser coauthored with the renowned Talcott Parsons Economy and Society, a 300-page book of mostly theoretical deliberations and insights, which starts with the following sharp and programmatic statement:

“This volume is designed as a contribution to the synthesis of theory in economics and sociology. We believe that the degree of separation between these two disciplines — separation emphasized by intellectual traditions and present institutional arrangements — arbitrarily conceals a degree of intrinsic intimacy between them which must be brought to the attention of the respective professional groups.” (p. xvii)

But the book, that elaborated on the role of institutions in the economy, got a negative reception by economists and failed to ignite an interest among sociologists, mainly because of insufficient empirical data and the ascendancy of static Parsonian categories.

In 1963 Smelser published a modest in its size but thought-provoking and thorough The Sociology of Economic Life (open access). This book was a precocious work that did not immediately advance distinct new lines of research (although the publisher initiated its second edition in 1976); but in retrospect, one can say that it was a pioneering work that adumbrated the directions of renascent economic sociology. On the page 32, Smelser articulated the analytical focus of economic sociology, which since then has become the point of departure for various definitions of the nowadays vibrant field of study:

“Economic sociology is the application of the general frame of reference, variables, and explanatory models of sociology to that complex of activities concerned with the production, distribution, exchange, and consumption of scarce goods and services.”

The Handbook of Economic Sociology, edited by Smelser and Richard Swedberg and published in 1994, already marked the intermediate pick of the discipline, following the 10-15 fruitful years in which ‘new’ economic sociology had enjoyed remarkable developments propelled by the researches of Mark Granovetter and others in the US and Europe. The second edition of The Handbook (2005) undoubtedly signified the scientific culmination of this evolutionary process of creation and dissemination of knowledge on the ontological embeddedness of state-economy-society; the fountain of knowledge which vigorously continues to well and gush.

In 2013, Berkeley’s Bancroft Library released a massive volume consisting of dozens of interviews with Neil Smelser, in which he told about his professional lifelong path and the institutional history of US social science. Amidst hundreds of pages of intriguing stories and thoughts, Smelser revealed that as a consultant to the Economic Sciences Nobel Prize committee he recommended against awarding Chicago School economist Gary Becker:

“[His nomination was for] the extension of rational choice to the analysis of racial discrimination. He became involved in the analysis of family… and marriage rates and marriage bargains and so on. He did it in strictly economic terms. And he and his colleagues developed a rational choice theory of drug use… All within a very orthodox economic framework…. I played exactly the devil’s advocate for the value of these extensions of economic reasoning into areas which did not lend themselves to it. In other words, I thought it was an intellectually erroneous adventure on his part and bold, to be sure, and consistent and persuasive, as Becker always is. But nonetheless, I thought it was not intellectually worth what was claimed for it and the results that were argued for. I simply had a judgment that this was not the right way, right intellectual way to approach institutions which were fundamentally not economic in character. That’s my take on what is called economic imperialism.” (p. 542)

I would like to conclude this unforgivably brief depiction of the small portion of Neil Smelser’s academic journey by rereading his words (p. 412-3) which I found not just descriptive in regard to past economic sociology, but also prescriptive to future economic sociologists.

“The impulse of economic sociology has been critical of orthodox economics, not Marxist economics, largely for its artificiality and assumptions about rationality and assumptions about atomism of the individual actor and that social institutions play a role in dictating taste, behavior, conflict, market processes. It’s more of a polemic, in a negative sense, on the world view of economists, and an attempt to substitute a world view that personal interaction, social institutions, cultural understandings play a role in dominating economically relevant action… Economic sociology became primarily analytic and did not have a single ideological thrust to it. It’s diverse and eclectic from the standpoint of perspectives… Economic sociology, intellectually, is one of the strongest fields in sociology.”

***

Join Economic Sociology and Political Economy community via

Facebook / Twitter / LinkedIn / Instagram / Tumblr

Dear Oleg,

Your piece on Smelser was extra good and helpful, I thought!

Thanks for writing it and all your other fine postings!

Best,

Richard

[…] > Neil Smelser: “Economic sociology, intellectually, is one of the strongest fields in sociology” […]