Transplantees Find Catharsis in Holding Their Old Hearts

An initiative reunites transplant recipients with their former organs for education and therapy.

Kamisha Hendrix’s heart lay on the table between us. Seventy days ago, this heart had been beating inside of her, back behind the dark scar that plunged into the neckline of her blouse.

“No—my heart didn’t beat,” Hendrix clarified. “It trembled.”

The chemo used to treat her non-Hodgkin's lymphoma had damaged her cardiac muscle irreparably, reducing its strength to 15 percent. She regularly lapsed in and out of consciousness. “I felt like I was moving through mud,” she recalled.

Hendrix looked at the heart on the table, the organ she had carried for 44 years, and spoke in its imaginary voice. “You wanna live?” She gave the heart a whimpering intonation. “Okay, I'll give you another beat.”

She switched back to her own voice, “Thank you, heart. Thanks a lot, friend.”

Three months ago, Hendrix’s mother, Carolyn Woods, had already written her obituary and tucked it away in a drawer. The theme, Woods explained, was For Whom the Bell Tolls. “It was about everyone coming to pay their last respects—and the people are the bell. All that crying and wailing would be the people tolling for her.”

Ultimately, the story of Hendrix’s heart did end in a funeral. Somewhere, on a clear May morning, an organ donor died. Within hours, Hendrix received a new heart.

The transplant saved Hendrix’s life, and yet—it would also be technically true to say that in the process, a part of her had died. We were in Dallas, Texas, at the Baylor Heart and Vascular Center to reunite Hendrix with her native heart and reflect on what it means to live without it.

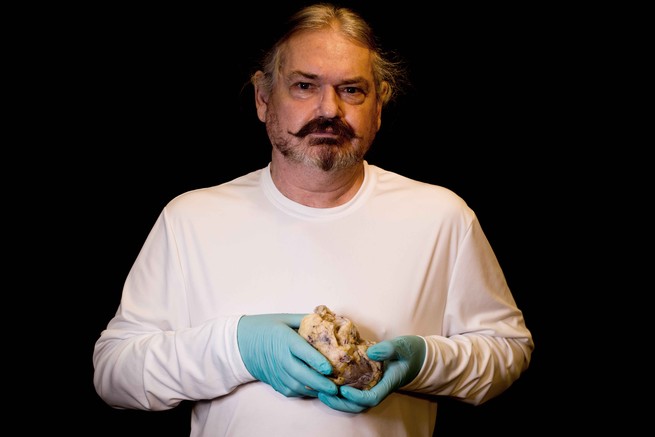

The idea for this kind of encounter originated with William Roberts, Baylor’s chief cardiac pathologist. In 2014, Roberts began the Heart-to-Heart program, inviting cardiac transplant patients to see and hold their former organs. The primary objective was education. Roberts delivers a health lecture with the patient’s own heart as Exhibit A.

For transplantees, compliance with doctors’ lifestyle instructions is critical to recovery and longevity. One recent study found that in the domains of diet, exercise, medication, and tobacco avoidance, noncompliance ranged from 18 to 37 percent. Furthermore, compliance was observed to decrease over time.

While Hendrix’s heart failure was primarily due to another cause, her condition was exacerbated by unhealthy lifestyle choices—a factor that impacts nearly all heart-transplant patients. With Heart-to-Heart, Roberts has found a way to clearly demonstrate the effect of these choices on the heart itself. According to a study co-authored by the cardiologist, 75 percent of program participants reported that the experience has changed their health-related behaviors “to a great degree.”

Roberts begins each session with raw statistics.

“In the United States, there are 6 million people living with heart failure,” he lectures in a honeyed Georgian accent. “Every year, only about 2,200 of those people receive heart transplants. So, you are very, very special. You’ve been given a second chance.”

Unceremoniously lifting the surgical cloth that covers the heart, Roberts describes what he sees. The history of the heart is there, incontrovertibly embedded in the organ. Most are cocooned in hard yellow fat.

“If you dropped this in the Mississippi,” Roberts opines, “it would float all the way to the Gulf.”

“Oh my god!” Hendrix gasped. “Look at all that fat! I guess those chips have gotta go.”

“That’s right,” Roberts replied. “And those cows, chickens, and pigs on your plate.”

In addition to education, the reunion also provides an opportunity for closure—a benefit that Roberts didn’t initially expect. After facing death—what transplantee John Bell prefers to call “the abyss”—survivors are frequently left traumatized. That reality is apparent in the standard warlike medical rhetoric, with doctors and patients alike speaking the language of soldiers. Together they fight their battles, target the enemy, eradicate and annihilate. With the focus on winning, dedicated opportunities to stop and reflect are rare.

Tina Sample’s ordeal began with a massive heart attack that was misdiagnosed as a gastrointestinal issue. After days of breathless agony, she was finally correctly diagnosed at a different hospital. “I had what they call ‘the widowmaker,’” she recounted, “100 percent blockage. I had a massive amount of blood clots throughout my heart. The doctor had never seen anything like it in his 24 years of practicing medicine. He called me a miracle.”

In the months that followed, Sample lived in constant fear of death. “I was just so scared every night,” she confessed. “I had this terror that this could be my last night on earth, so I’d try to keep myself awake. I would keep myself awake until 4 or 5 a.m. I wanted to see my son graduate college. I wanted to know my grandkids. There were so many things I wanted to see.”

James Murtha had been healthy his entire life. “I’ve never broke a bone in my body,” he insisted. “I’ve never really been sick at all, except for the flu once and chicken pox when I was a kid. So this—when it hit, it hit hard.”

Murtha had been driving home from work when he began to shiver and sweat. It was a heart attack. Later, he recalled being in a hospital bed, on life support, his liver and kidneys failing. He says he had a vision of his mother, lying in a similar bed half a century earlier. It was one of his earliest memories.

“I basically went back in time,” he began. “I was five. They brought us all in, the night she passed away. I remember her telling me, ‘You’re gonna be good for your dad now, aren't you?’ There were five of us kids, and she made my dad promise that he'd keep us all together.” She died in that bed, at the age of 25, from a rare cancer.

As Murtha lay suspended between life and death, the visions continued. His wife grasped his hand as he described what he called an out-of-body experience: “I was in this place looking for my older brother Mike. We had been talking about getting together. He was a dreamer. Oh, it had been over 30, 40 years since we’d played together. And then he died. But, I was in this place, like a green forest, meadows, and there were these bright figures all around. And, there was this one figure, I couldn’t—it was just really bright, and he was in a robe like Jesus. And, he told me, ‘Your brother is home, you need to go find yourself.’”

Murtha awoke in an intensive care unit, with a new heart bounding in his chest. His old heart went first to the pathology lab for an autopsy. At that point, Roberts claims, “99.5 percent of hospitals throw the hearts away. They just don’t have the space to keep them.” Baylor is different, however. Their lab contains thousands of hearts in permanent storage, making it one of the most extensive cardiac research facilities in the world. The availability of these organs creates a unique opportunity for a program like Heart-to-Heart. Each transplant patient at Baylor is routinely informed about the option, which is promoted as an educational opportunity.

On the day of a viewing session, clinical coordinator Saba Ilyas carefully retrieves and prepares each organ. The patients come in, sometimes alone, sometimes with their families, all eyeing the tray with the bulging surgical towel.

Hendrix had expected to see something “black and shriveled, probably three times the normal size, and just jello-like.”

Bell had expected a big red ideograph, “like when you open a Valentine’s card.”

“It wasn’t like that at all though,” he continued. “What it reminded me of, was a piece of roast beef.”

Under the glaring examination lights of the Baylor pathology lab, the visceral reality of what had actually happened to these people was an abstraction. I was there, holding a lump of raw meat in my hands, trying to feel the life that had once pulsated through it. Across culture and time, the heart has been a metaphor for love, for valor, for the soul itself—for everything we can sense but never touch. Here too, at the viewing, it was evident, by the gentle reverence it inspired, by the tender way in which it was held—the meaning of this organ transcended its mere function and form. Each transplantee was left to interpret the significance of this experience for themselves.

“The whole time you’re holding your heart,” Bell described, “your brain wants to have a little conversation with you—like you shouldn’t really be doing this. This is not normal. And, you’re like—well, but here it is. I have my heart right here in my hands, and it’s normal to me.” Bell later recalled opening his eyes for the first time after his operation. “In a very poignant moment, I told my new heart that I’d take care of it as best I could for as long as I could.”

Hendrix speculated about the identity of her donor. Based on the frenetic surge of energy she reports experiencing since the transplant, she mused that “it feels like a tennis player.” Afterwards, she spoke again about the borrowed life source she carries inside of her. “It’s like the donor, in some way, is still alive. I think, if the donor was a happy person, they’re still a happy person, it just manifests itself through me.”

For Sample, the heart in her chest feels palpably foreign. She has dreamed about her unknown donor—envisioning him kneeling before her, offering up his heart with his own two hands. She has stopped using the common phrase “my heart” to describe her feelings. She has replaced it, sometimes haltingly, with “my mind.”

Bell held his former heart in front of his chest, with hands that shook from the drugs he must take for the rest of his life to keep his body from rejecting his new organ. The survivor found himself unexpectedly smiling. “To see my native heart, this thing that had caused so much pain and heartache, and to be able to walk away [from it]—I felt victorious.”

Hendrix thought of God, and of all her mother’s fervent prayers. “It made me feel how truly blessed I am to be here.”

Sample’s emotions overwhelmed her. “When something is gone that’s been a part of you—the thing that gives you life—there’s a sense of loss. There’s a grieving process that you have to go through. It’s crazy, but it’s like a person. It’s dead. My heart is dead, and there it is, lying on the table right there. If your mind goes to that place, then you can’t help but feel that loss. I told my heart ‘I’m so sorry I didn’t take care of you better.’ It brought tears to my eyes, truly. I needed to say goodbye.”