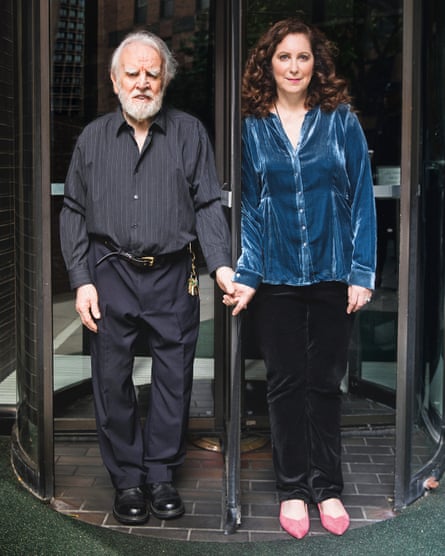

‘Goodnight, honey,” I say. “Goodnight, sweetheart,” my husband says. I turn over to go to sleep. He turns to the door to catch the train home.

That has been my nightly routine for 25 years. Well, not every night. Occasionally, there’s some reason John needs to be in my neighbourhood early in the morning. Or, now that we’re old – correction: with our 29-year age gap, I’m old, he’s ancient – there’s the issue of his knees, and if they’re particularly bothersome, he might brave a night with me and our 15-year-old twin sons instead of the New York subway. But, for the most part, he arrives around 4pm, I make dinner for 6pm, we obsessively watch the news for a few hours (thank you, President Trump) and later in the night my husband goes to his apartment a couple of miles away.

Here’s what my marriage is. We have argued at Walmarts across America on vacations. We’ve secretly congratulated ourselves on our stellar DNA when our son Henry brought home a chess trophy. We’ve burned dinners, fretted about tax returns, held hands when we’re too tired to do anything else, made hasty trips to the ER when the kids used the bed as a launchpad to nowhere. In other words, we’ve had a marriage like any other. Except for this one thing: John and I have never lived together. Is that so strange?

Depends who you ask.

While I have blithely been living what I considered the most tediously conventional existence, I have somehow become cool, or at least part of a gently escalating trend. The current infelicitous phrase, coined in 2004 by sociologist Irene Levin, is that I’m part of an LAT couple, Living Apart Together. That is, two people who are married or in a long-term committed relationship who do not live under the same roof. (Canadian Sharon Hyman, who is directing a movie on the subject, has come up with a phrase guaranteed to appeal more to punsters: “apart-ners.”) Studies on the subject vary, and different countries define LAT differently. But a recent reckoning in the US estimates that 3.5 million Americans (3% of all married couples) are LAT. In the UK, where not just marriage but long-term partnerships are accounted for, that number rises to 9%.

The Canadian government has looked at this phenomenon extensively, and determined that, as we get older, those LAT relationships became more and more non-transitional – that is, we became more sure that we are going to live separately and stay that way. Of course, Canadian researchers are failing to ask the critical question: “Would you change your mind about living separately if you were moving in with our prime minister?” That’s the only way to really know how committed LATs are.

It’s not as if this is the most outlandish arrangement in the world. I used to say John and I were very Woody and Mia, until that comparison lost its cachet. But still, historically there are many couples who made it work. Anita Hill and Margaret Drabble are both known for having successful relationships with people who did not share their living space. Tim Burton and Helena Bonham Carter. OK, they’re divorced now, but it worked for years, which counts as success. Then there were the intellectuals Simone de Beauvoir and Jean-Paul Sartre, and the artists Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera. Maybe the writer Robert Parker and his wife got it exactly right: they divorced and then got back together, with the caveat that they create two entirely separate apartments in one huge home. They had to issue invitations to each other to visit. They also built a third kitchen, presumably the Switzerland of their residence.

I’ve never understood why living separately is a big deal. I want the same love and commitment as anyone else; but why do I have to live in the same place to achieve it? Particularly if you find that you fundamentally love each other, but have very different ways of living and spending money. While John exhibits, shall we say, the frugality of his Scottish ancestors, he nevertheless likes decor that would be best suited to the set of Downton Abbey: his uptown studio consists of two grand pianos and family furniture that I believe is haunted. I like stuff that is new, light and whimsical – I say whimsical, he says appalling. Why should I have to live without my light-up plastic owls if they give me pleasure? The truth is, we don’t agree on much, except each other.

Still, for most people, the idea of living separately just seems a bizarre fantasy. “My relationship is entirely co-dependent,” one friend says. “My husband and I work together, every day, in my studio apartment, on the same couch. I don’t even fantasise about getting my own apartment any more. I just fantasise about getting a door.”

But among those I know who are LAT, it’s not some sort of grudging compromise. The people I know wouldn’t have it any other way. “The thing most people ask me is, ‘What is the longest you have been apart?’” says Ken Carlton, about his marriage to his wife, Geri Donenberg; she is a professor of medicine in Chicago, he a writer in Brooklyn. “The better question is, ‘What is the longest you’ve been together?’ And that would be 10 days, on a recent vacation.” It’s a second marriage for both. While Jewish dating site JDate brought them new love, they had children from earlier marriages and jobs in different cities – not to mention independent spirits. So they stayed rooted, and have had weekly dates for the 12 years of their marriage.

“I think the secret is that, generally speaking, one is genuinely excited when you don’t have to be together,” says Tim, an executive in television sales from New York who has been with his partner, Mary, for six years in separate homes (and, yes, the fact that both came out of difficult marriages does play a role).

For Lisa Church of San Francisco, who spent 10 years happily with her partner in separate homes – five years before having their daughter, Rena, five years after – “it just felt right. We’d both been married before, we both cherished alone time.” Though they got more grief post-Rena, Church notes.

So did we. While living apart may have seemed kind of exotic to most friends pre-children, once I had twins, it became more suspect. Henry and Gus live downtown with me. Friends counselled me after the kids were born that now John would simply have to move in with me; after all, what would the children think? Well, the fact is, children don’t think much at all about these things. Dad is around for dinner, and was there to put them to sleep. As they got older, their needs changed. John used to arrive ridiculously early in the morning to help me get them off to school, until that became insane; I’ve done it now, happily, for years. (This is admittedly a luxury many don’t have: I work at home, so it’s not as if I have a mad single-mother scramble to get to my office.) We went on our share of family vacations, though the three of them are such homebodies that their best vacations, my sons admit now, were when I went away and their father stayed home with them.

But when my son Gus was diagnosed with autism, the criticism from the outside world really ramped up. Now my older husband was not living with me for a very specific reason: because he couldn’t stand to be around a disabled child. And I would have to explain, “Nope! It’s just me he can’t stand.” (This isn’t quite true either, but it does amuse me.)

Gus plays no part in why we don’t live together. Quite the opposite. Gus is our glue, and he, along with his neurotypical twin, Henry, is John’s world. Moreover, Gus and his father’s sensitivities are well matched. While my husband never received an official diagnosis of autism, it’s safe to say he is not entirely neurotypical. Both Gus and his father are completely literal-minded: if you tell John, “I’ll call you back in a minute,” he will sit by the phone for an hour with steam coming out of his ears because, well, you said a minute. Both hate noise. Gus and John are both fastidious, and are pained at my sloppiness and general clutter. The only unfortunate part of this scenario is that Gus has to live with me. There was never a discussion about the twins living with John – he has a studio apartment.

My arrangement has sometimes been a source of envy, and sometimes pity. “Oh, that’s fine for those who can afford it,” sniffed one acquaintance, years ago. She lived in a midwest suburb. I didn’t want to explain to her the exigencies of living in Manhattan; that, actually, given how long ago we’d acquired our separate apartments, moving in together would have involved less space for much more money.

If people tend to assume you’re wealthy if you live separately, there’s one other assumption that’s even more prevalent about LATs. It’s even an assumption my own son has made. One night recently, John needed to stay over; he had a doctor’s appointment near me early in the morning. Gus does not like his routine interrupted and was trying to usher John out the door at his usual time. But Henry is a neurotypical teenage boy, and has other things on his mind. When John and I headed to bed, my room had been turned into a massive fire hazard. Henry had found candles, including precariously propped-up birthday candles, and dug out a couple of glasses and some cheap white wine. Clearly, he was a little worried about his parents’ capacity for romance.

He needn’t have worried. Several years ago, a survey of 2,500 couples conducted by Dietrich Klusmann at the University of Hamburg showed that, while lust between men and women is pretty equal at first, a woman’s desire begins to decline steadily after the first year, and continues to do so as the relationship progresses. The exception? Women who don’t live with their partners: they retain desire much longer and more intensely than those who cohabit.

And is it really such a surprise that those of us who do not see our mates’ intimate personal habits every day might have a slightly more romanticised view of them? Indeed, I think I had been married 10 years before I discovered my husband had no front teeth, the result of an unfortunate mountain-climbing accident in his 20s. He took out the bridge and I was a little unprepared. You may have heard my shriek. As far as I’m concerned, those innocent 10 years were good ones.

I’m not going to say the LAT lifestyle doesn’t have its drawbacks. A friend who lives in New Jersey and has never lived with her husband acknowledged the positives – privacy, autonomy, absence making the heart grow fonder/not taking each other for granted, the ability to have opposing preferences without fighting – while clearly delineating the negatives, too: “lack of meaningful time together, hard to create traditional family atmosphere for children, constant running back and forth for the thing you left in the other place that you suddenly need.” Those things are often tiny but critical. The night before, the annoyance involved making a special dinner and realising she did not have a garlic press in both homes. For John, the biggest nuisance is his creakiness: the travelling back and forth is not always so great. There may be a time when we have to make the ultimate compromise if he finds the daily trip too burdensome. But not yet. We’re both content.

I believe that I would not be married if we had lived together, and moreover, that if more people lived separately, marriages would be saved. “This is the way the world ends, not with a bang but a whimper,” TS Eliot wrote, and the same could be said of many marriages. It’s the whimper of the quotidian that often grinds us to a nub. I think about writer Debra Nussbaum Cohen, who wrote this about her own LAT dreams on Facebook: “It is a fantasy of mine to be able to look forward to being together rather than aggravated by each other’s tics and habits.”

There were quite a few (virtual) sympathetic nods after Nussbaum’s comment; a few others had actually tried to set up LAT arrangements and failed. “A committed relationship in two houses was my objective in my last serious relationship,” noted one woman, a content strategist in Colorado. “I liked the idea of individual spaces... he couldn’t wrap his head around it. Even though he didn’t like my daughter and I didn’t like his dog, to him, my need for space showed that I didn’t care; it was 24/7 or nothing. He chose nothing and now I feel I dodged a bullet.”

In The All-Or-Nothing Marriage, Northwestern University professor of psychology Eli J Finkel cites several studies that point to how solid LAT relationships can be. In one study, the sociologist Charles Strohm showed that Americans who live apart perceive just as much emotional support from their partner as those who live together. Another researcher, Birk Hagemeyer, suggests that some people benefit more than others from living apart, specifically, those who want love but are nevertheless slightly cranky loners.

“Although having an independent personality predicts lower relationship quality on average, that’s not the case when people live apart,” Finkel writes. “And although spending more time with one’s partner is linked to greater relationship satisfaction among independent people who live apart, it is linked to lower relationship satisfaction among independent people who live together.”

Translation: if you’re like me or my husband, you live together at your peril.

Make no mistake: we’ve had our bad periods. It’s a marriage. But it’s living separately that has saved us. Because, if there is space, there is consideration. In 25 years of marriage, neither of us has said something so heinous that it cannot be unsaid. And that is simply because when we are angry, we are not forced to look at each other and swell with hatred. Absence not only makes the heart grow fonder, it makes that heart slow down.

Living separately has been a critical tool in our arsenal to make marriage work. And we both knew, without explicit discussion: separate apartments don’t mean separate lives. Our lives are just as enmeshed as anyone else’s, even if we don’t have to consult each other about what curtains we want to buy or whether my tendency to play Gloria Gaynor at top volume is joyous or, as John has put it, “a soul-destroying experience”.

To those who say I am missing out on the intimacy of a true relationship, I can say only this: we all have different ways of experiencing intimacy. If my husband were run over by a bus tomorrow, I would very much want to be married again. I love being married. I love having that special one person in my life. I just can’t imagine wanting to do it again under the same roof, however large that roof may be.

Unless it’s the Canadian prime minster. Word on the street is that Justin Trudeau really loves plastic light-up owls.

Judith Newman is the author of To Siri, With Love (£16.99, Quercus). Some names have been changed.

Commenting on this piece? If you would like your comment to be considered for inclusion on Weekend magazine’s letters page in print, please email weekend@theguardian.com, including your name and address (not for publication).

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion