The recent CCleaner malware outbreak is much worse than it initially appeared, according to newly unearthed evidence. That evidence shows that the CCleaner malware infected at least 20 computers from a carefully selected list of high-profile technology companies with a mysterious payload.

Because the CCleaner backdoor was active for 31 days, the total number of infected computers is "likely at least in the order of hundreds," researchers from Avast, the antivirus company that acquired CCleaner in July, said in their own analysis published Thursday.

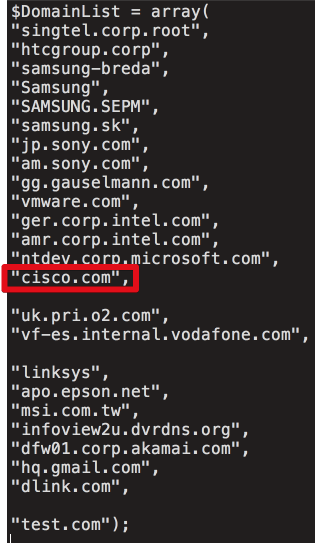

From September 12 to September 16, the highly advanced second stage was reserved for computers inside 20 companies or Web properties, including Cisco, Microsoft, Gmail, VMware, Akamai, Sony, and Samsung. The 20 computers that installed the payload were from eight of those targeted organizations, Avast said, without identifying which ones. Again, because the data covers only a small fraction of the time the backdoor was active, both Avast and Talos believe the true number of targets and victims was much bigger.

More fileless malware

The second stage appears to use a completely different control network. The complex code is heavily obfuscated and uses anti-debugging and anti-emulation tricks to conceal its inner workings. Craig Williams, a senior technology leader and global outreach manager at Talos, said the code contains a "fileless" third stage that's injected into computer memory without ever being written to disk, a feature that further makes analysis difficult. Researchers are in the process of reverse engineering the payload to understand precisely what it does on infected networks.

"When you look at this software package, it's very well developed," Williams told Ars. "This is someone who spent a lot of money with a lot of developers perfecting it. It's clear that whoever made this has used it before and is likely going to use it again."

Stage one of the malware collected a wide assortment of information from infected computers, including a list of all installed programs, all running processes, the operating-system version, hardware information, whether the user had administrative rights, and the hostname and domain name associated with the system. Combined, the information would allow attackers not only to further infect computers belonging to a small set of targeted organizations, but it would also ensure the later-stage payload is stable and undetectable.

Now that it's known the CCleaner backdoor actively installed a payload that went largely undetected for more than a month, Williams renewed his advice that people who installed the 32-bit version of CCleaner 5.33.6162 or CCleaner Cloud 1.07.3191 reformat their hard drives. He said simply removing the stage-one infection is insufficient given the proof now available that the second stage can survive and remain stealthy.

The group behind the attack remains unknown. Talos was able to confirm an observation, first made by AV provider Kaspersky Lab, that some of the code in the CCleaner backdoor overlaps with a backdoor used by a hacking group known both as APT 17 and Group 72. Researchers have tied this group to people in China. Talos also noticed that the command server set the time zone to one in the People's Republic of China. Williams warned, however, that attackers may have deliberately left the evidence behind as a "false flag" intended to mislead investigators about the true origin of the attack.

The CCleaner campaign is at least the third in two months to work by attacking developers of legitimate software used and trusted by a large or influential base of users. The NotPetya ransomware worm in July was seeded after attackers infected M.E.Doc, a developer of a tax-accounting application that's widely used in Ukraine. The attackers then caused the company's update mechanism to spread the ransomware. Last month, network-management software used by more than 100 banks worldwide was infected with a powerful backdoor after the tool developer, NetSarang, was hacked. Such supply-chain infections are concerning, because they work against people who do nothing more than install legitimate updates from trusted vendors.The picture coming into focus now looks serious. Attackers gained control of the digital signing certificate and infrastructure used to distribute a software utility downloaded more than 2 billion times. They maintained that control with almost absolute stealth for 31 days, and, during just four days of that span, they infected 700,000 computers. Of the 700,000 infected PCs—again, believed to be a fraction of the total number of compromises during the campaign—a highly curated number of them received an advanced second-stage payload that researchers still don't understand. It's almost inevitable that more shoes will drop in this unfolding story.

Post updated to correct subheadline. The companies are known to have been targeted, but not yet known to have been infected.

Listing image by portal gda

reader comments

224