Hong Kong history skewed by single-language barrier

Much of the territory’s rich past has been documented in academically overlooked Cantonese

History, it is claimed, is written by the victors. That’s usually true, initially, at least. With the passage of time, as lengthier and more nuanced perspectives on past incidents develop, different (and often significantly revised) versions appear. How accurate accounts are, however, remains dependent on the quality of source materials. The statistician’s age-old lament of “garbage in, garbage out” applies as much to the discipline of history as any other form of data analysis.

To better understand places with sharply varied versions of the past, it’s worth considering the languages used in primary source materials. Many earlier histories of Hong Kong relied almost entirely on English-language sources. This deficiency created bias (however much resisted by individual historians) because potentially transformative information available only in Chinese sources often remained unexplored.

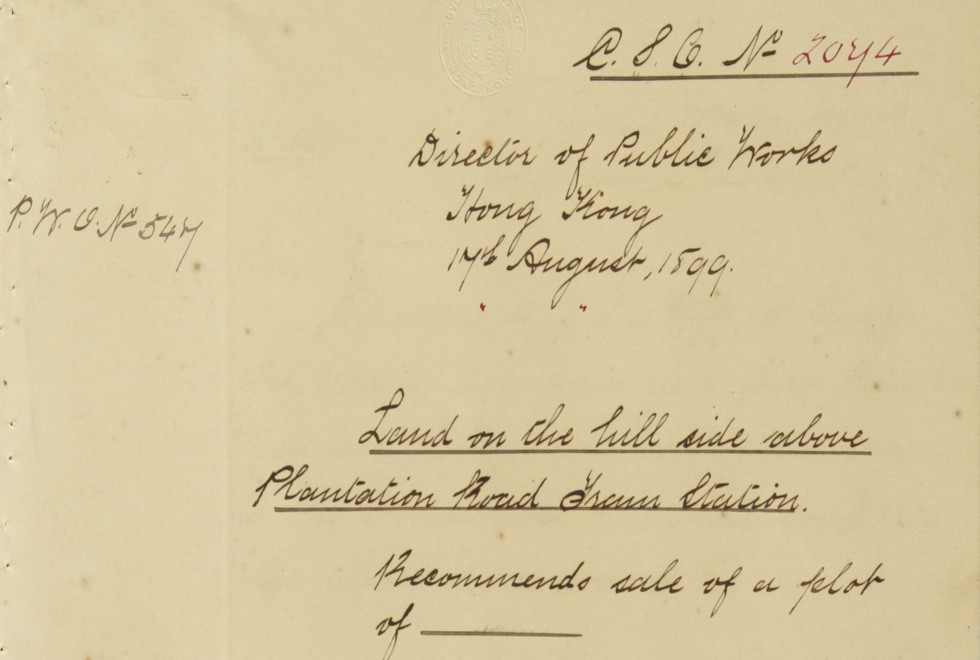

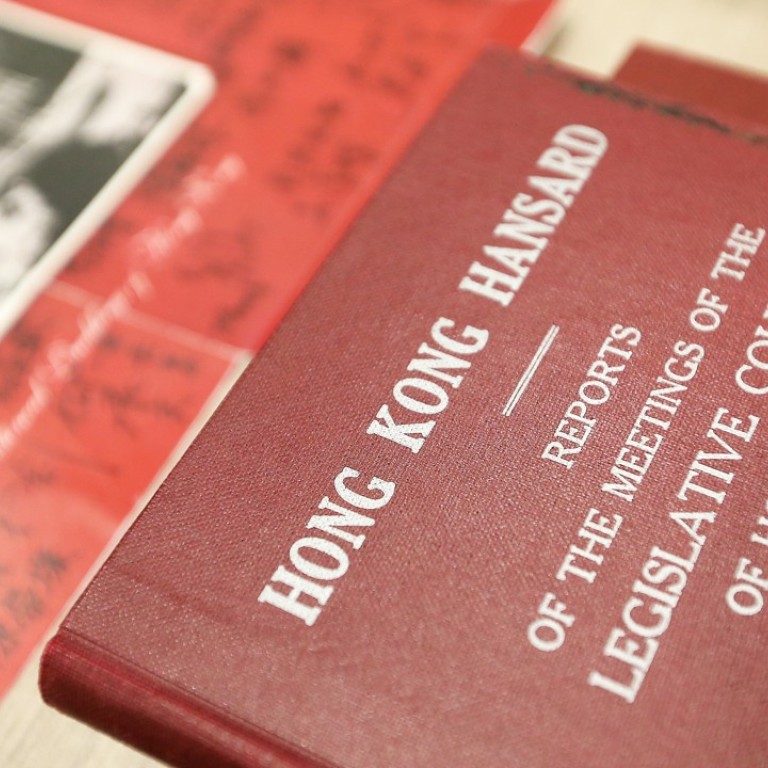

Hong Kong’s official sources – such as lands records, court documents, legislative proceedings and official minutes – are mostly in English, which remained the sole official language until 1974. Records accumulated by community organisations and consultative bodies such as the Tung Wah Hospital Committee and Po Leung Kuk (to cite just two of many examples) were mostly kept only in Chinese. This creates challenges for researchers only able (or, in some instances, only willing) to use one language.

To access information from “the other side of the hill”, monolingual historians need research assistants, who must be given detailed instructions on what to look for. It’s an expensive, time-consuming process.

What’s more, unexpectedly worthwhile incidental material may not be immediately obvious until multiple files have been comprehensively explored, and this may not have been budgeted for in initial research funding proposals.

A major contemporary challenge is that some English-language primary materials have been translated (often indifferently) into Chinese, and many who use such materials in secondary works fail to reference the original for fact checking. Absolute howlers in terms of inaccuracy, in particular with spelling, are the inevitable consequence. Mistranslated names, phonetically transliterated from English into Chinese and then back again through guesswork, without checking the primary source, are an obvious example.

These occur far too frequently in Hong Kong’s English-language publications – especially newspapers. The Hong Kong tendency to settle for an appealing, marketable “story” over solidly researched – and often dry – factual detail remains popular. In turn, popular local myths and widely retailed urban legends gradually become accepted, hard-to-challenge “facts”.

Local “knowledge” can also play a part in historiographical shortcomings. While being born and raised in a particular place does afford some insight, that particular accident of birth doesn’t automatically confer detailed knowledge and textured understanding of the place’s history, culture and society. To be fully appreciated, the past – like anything else – has to be comprehensively studied, then reflected upon.

South African-born writer William Plomer, who lived most of his life in Britain, famously remarked of his own feelings towards his native land that “being born in an oven doesn’t make a kitten a biscuit”, and the same observation also holds good in Hong Kong.