‘Pure Poison’ for a Scholarly Career

Researchers have spent centuries failing to decipher a medieval manuscript’s baffling drawings of plants, naked women, and astrological symbols. Is it worth the effort?

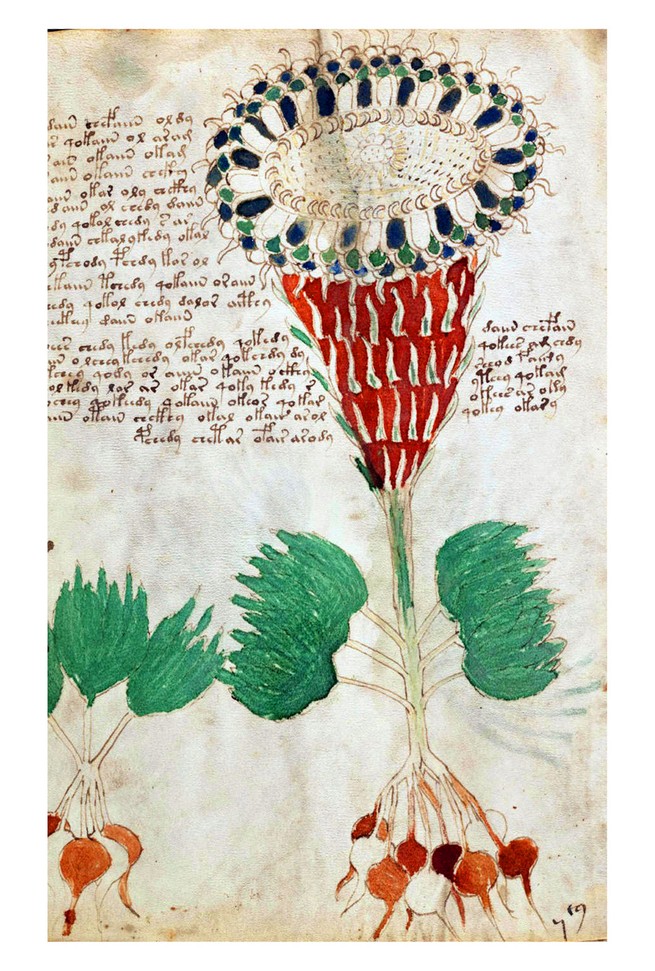

It’s an approximately 600-year-old mystery that continues to stump scholars, cryptographers, physicists, and computer scientists: a roughly 240-page medieval codex written in an indecipherable language, brimming with bizarre drawings of esoteric plants, naked women, and astrological symbols. Known as the Voynich manuscript, it defies classification, much less comprehension.

And yet, over the years a steady stream of researchers has stepped up with new claims to have cracked its secrets. Just last summer, an anthropologist at Foothill College in California declared that the text was a “vulgar Latin dialect” written in an obscure Roman shorthand. And earlier that year, Gerard Cheshire, an academic at the University of Bristol, published a peer-reviewed paper in the journal Romance Studies arguing that the script is a mix of languages he called “proto-Romance.”

Thus far, however, every claim of a Voynich solution—including both of last year’s—has been either ignored or debunked by other experts, media outlets, and Voynich obsessives. In Cheshire’s case, the University of Bristol retracted a press release highlighting his paper after other experts roundly challenged his research.

Andreas Schinner, a physicist, recounted in an email a rumor that the Voynich manuscript can be “pure poison” for a scholarly career, because when studying the manuscript, there’s “always an easy option to make a ridiculous mistake.”

“The academic world is a jungle,” wrote Schinner, who first applied statistical analytics to the manuscript more than a decade ago, “and like in any jungle, it is not recommended to show even potential weakness.”

All we know for certain, through forensic testing, is that the manuscript likely dates to the 15th century, when books were still mostly handmade and rare. But its provenance and meaning are uncertain, making it virtually impossible to corroborate any claims about its contents against other historical materials.

So why are so many scholars and scientists driven to solve the puzzle? For many, it’s the ultimate opportunity to prove their analytical skills in their given field. For others, it’s a chance to test promising new digital technologies and artificial-intelligence advances. And for some, it’s simply the thrill of the hunt.

The manuscript was acquired in 1912 by Wilfrid Voynich, a Polish rare-book dealer. Resembling a modern book rather than a scroll, it is full of looping text handwritten in an elaborate script, accompanied by lavish illustrations. The find failed to make Voynich rich, but the manuscript has continued to make headlines for more than 100 years, challenging researchers in many fields, including linguistics, botany, and machine learning. It now resides at the Beinecke Library at Yale University.

At first, it mainly attracted humanities scholars. In 1921, William Newbold, a philosopher at the University of Pennsylvania who had an interest in cryptography, claimed that a 13th-century friar wrote it as a scientific treatise. Newbold believed that each arcane letter was actually a collection of minuscule symbols readable under proper magnification, which would have meant the microscope was invented centuries before we thought. After Newbold’s death, John Manly, an American literature professor and fellow code breaker, disproved Newbold’s theory, showing that his methods were arbitrary and scientifically unreliable.

William and Elizebeth Friedman, two founding figures in modern cipher-breaking, continued to apply code-breaker techniques to the manuscript. Though they studied other texts and were recruited to crack messages during both world wars, they were never able to land on a solution to the Voynich.

During World War I, the Friedmans had to perform their calculations by hand, but in the following decades, IBM’s punch-card tabulating machines made the process much faster. Working with the National Security Agency when it was formed in the 1950s, William and other code breakers pursued an interest in the medieval manuscript (there’s even a copy of it in the NSA’s internal library). Because the manuscript was unclassified, Cold War code breakers could use it to illustrate cutting-edge computational analysis techniques to their colleagues without using real Soviet messages.

Recent Voynich research also relies heavily on computer analysis, though with far more sophisticated tools. Lisa Fagin Davis, a medieval scholar who has followed Voynich research since the 1990s, says the “incredible advances in computing power” have also helped debunk proposed solutions: “We have a way to analyze and critique solutions that are published in a sophisticated and almost inarguable way.”

The mysterious illustrations are also a draw for some researchers. Arthur Tucker, a botanist, has argued since 2013 that the Voynich plants were native to the Americas. In a recent email, he said his noncomputational approach of interpreting each of the botanical illustrations stirred up anger from more data-focused scientists, whose methods he dismissed, without elaboration, as “circular reasoning.” But his theory hasn’t caught on with either botanists or data scientists.

As for Schinner, he said he was drawn in by other scientists’ attempts: “Perhaps I just wanted to find out if I could do better than this.”

Using “random walk mapping” drawn from mathematics and applied to strings of characters, he suggested in 2007 that the text was generated from an underlying stochastic process—randomness like the frequency of falling raindrops—and not a natural language, which has structure. A second paper he co-wrote in 2019 elaborated on his theory to propose a possible generating algorithm for the text, simple enough that a medieval scribe could have done it as a hoax. Their research seems to support the idea that the manuscript is meaningless.

Other recent studies contradict Schinner’s conclusion. A team of scientists in Brazil and Germany in 2013 ran their own statistical analyses and drew the opposite conclusion: The text was likely written in a language, and not randomly generated. In 2016, Greg Kondrak, a computer scientist at the University of Alberta, and his student, Bradley Hauer, deployed a machine-learning algorithm trained on 380 translations of the same block of text to propose that the content is jumbled-up Hebrew, written in a strange script.

A Turkish engineer and his son, meanwhile, theorize that the script is a phonetic transcription of a medieval Turkish dialect and plan to publish a paper on their findings in 2020. And a statistics paper published in November described how visual analysis of the letters identified patterns in the script itself that seem similar to other written alphabets.

“Everyone wants to be the one to prove it, to crack it, to prove your own abilities, to prove you’re smarter,” says Davis, the medieval scholar. One problem, she adds, especially with a complex medieval manuscript, is that researchers are specialists. “Hardly anyone out there understands all the different components” of the manuscript, she points out, referring not just to the illustrations but to things like the binding, the inks, and the handwriting. “It’s going to take a whole interdisciplinary team.”

She cites the controversy over Cheshire’s linguistic analysis as an example of the limits of scholarly publishing. Although his paper was peer-reviewed—ordinarily the gold standard of scholarly rigor—the reviewers were most likely specialists in Romance languages, because the paper was published in a journal of Romance studies. And peer review is often an opaque process, even for topics far less obscure than a 600-year-old manuscript. For his part, Cheshire remains confident in his work, drawing a distinction between himself and other would-be code crackers: He is right, and they are wrong. “Simple, really,” he says.

For other Voynich researchers, the main point is what you learn along the way. Over the past five years, journals covering computational linguistics, physics, computer science, and cryptology have published Voynich papers, some later debunked but many others outlining a new approach to analyzing the text rather than making a definitive claim to a solution. In the latter cases, the goal may primarily be showcasing new tools that can be applicable to other fields.

Artificial-intelligence algorithms, for example, often require large data sets for training and testing before they can be widely applied, and analysis of the Voynich manuscript can help physicists and other scientists test whether new number-crunching methods can identify meaningful patterns in large amounts of abstract data.

The 2013 Brazilian physics paper used the Voynich manuscript to illustrate how statistical-physics methods can be adapted to find hidden linguistic patterns and concluded that the text didn’t seem randomly generated. And Kondrak and Hauer’s machine-learning paper focused primarily on describing the language-analysis algorithms they used to detect Hebrew as the underlying language. Even if neither theory has been accepted as a Voynich solution, they may still prove effective in other arenas.

As Schinner put it, “You never know what will happen when you apply this or that method,” because the manuscript’s content remains unknown. Whatever researchers learn through trial and error can help them “develop techniques that can later be used on practical problems,” Kondrak says.

In the end, the manuscript may simply be an unsolvable mystery. Robert Richards, a historian of science at the University of Chicago, uses the codex to teach the concept of scientific paradigms, where a scientific theory comes to shape a field of research so strongly that scientists can’t always explain or identify anomalies outside of the theory.

Richards likens the Voynich text to the inscrutable language used by aliens landing on Earth in the 2016 film Arrival: We’re not even sure it’s really language at all, because it’s so far outside our linguistic paradigm. Though it looks like it means something, he says, “We could be assured of that only if we can translate it into our language.”

Who knows, he says of the Voynich manuscript: “It may be, after all, just a medieval nonsense joke.’’