Dutch is like shouting in a storm, says literary translator Sam Garrett

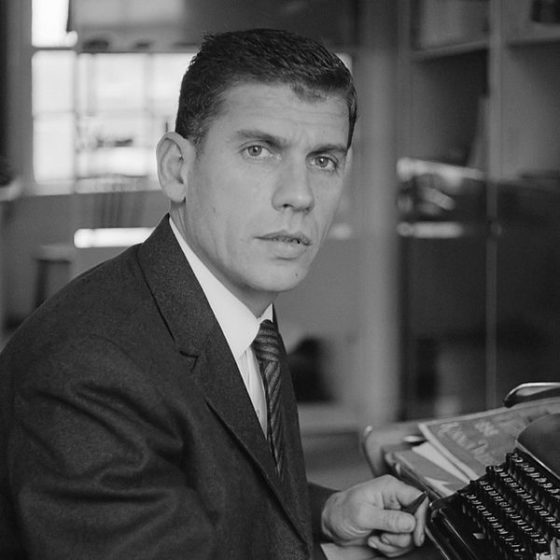

The work of award-winning translator Sam Garrett has been pivotal in bringing Dutch literature to a new, English-speaking audience. Deborah Nicholls-Lee discusses the quirks and merits of the Dutch language and Sam’s recommended reads for internationals new to Dutch fiction.

When you’re in a country on a visa that forbids you to work, you can have a lot of free time. Having swapped a straight-jacketed, Christian fundamentalist existence in the USA for open-minded Amsterdam, Sam Garrett (1956) spent most of the early 1980s reading – in Dutch. The language was new to him, but within two to three years, he had progressed to novels and, with author Gerard Reve (1923-2006), found something which strongly resonated with his own upbringing.

‘That background, that drabness and that feeling of something boiling under the surface in me, … I recognised that in De Avonden (The Evenings),’ he says. ‘And I think that’s what charmed me.’ And then he discovered Jan Wolkers’ Turks Fruit (Turkish Delight): ‘the volcanic eruption’, he says, of all that simmering heat. Both works would, many years later, be brought to an English readership through Garrett’s own translations.

Becoming a translator

First, though, was some tough love. The translations of Maarten Biesheuvel’s short stories that Garrett submitted for evaluation at the Literature Fund in his twenties came back riddled with edits. The aspiring translator was, smiles Garrett, ‘deeply insulted’ but hung onto one comment: ‘Translator shows a lot of promise’.

Undeterred, he later ‘had another go’, and made an appointment with Biesheuvel’s publisher, which eventually led to Translation Magazine running one of the stories. Garrett was in print at last. But then family life (he has four children) led him to prioritise a guaranteed income in journalism and advertising, only returning to translation in the 1990s when contacts seeking help drew him back into the literary translation circle.

One assignment was with Lonely Planet, who were launching a new line of travel literature. Garrett knew that this could be a big break. ‘I thought, I’ll do this. And I’m going to do it as well as I can and really try and get in there and make an impression,’ he says. It worked and was followed by a dream assignment: Arnon Grunberg’s Silent Extras. Since the finished work, in Garrett’s words, ‘seemed to sound like Grunberg’, many doors began to open.

The flexibility of Dutch

Though Tim Krabbé’s The Rider and Frank Westerman’s Ararat (non-fiction) earned him the Vondel Translation Prize, it is The Evenings of which he is most proud. ‘I did something right there,’ he says, carefully censoring any ego.

Reve’s ‘massive inventory of vocabulary’ and ‘switching back and forth between this highfalutin language and this almost crude language’ undermines, suggests Garrett, that often-heard denigration of Dutch in favour of English. ‘He’s a case in point of the great flexibility of the Dutch language,’ he says, and ‘a good example of how powerful and how subtle the Dutch language can be if put in the right hands’.

Another quality that Garrett appreciates in Dutch – and a challenge for any translator – is its succinctness. ‘In Dutch, there are things you can say in very few words that go right to the heart of the matter,’ he says.

‘That has partly to do with the fact that Dutch candour, which is part of the culture, also filters through into the language.’ He is persuaded that this way of communicating has a heritage to it which is often misinterpreted by newcomers. ‘The legendary Dutch rudeness is probably not really rudeness, but is probably just a way of shouting to each other in a storm or something,’ he says.

Language and culture are interlaced

Dutch is evolving, however, and a more diverse demographic in the Netherlands, believes Garrett, is raising interesting questions about whether the language is culturally sensitive enough. ‘Is going for the jugular the best way to accomplish your objectives?’ he ponders. ‘It’s something the Dutch have had to think about.’

Language and culture are interlaced, believes Garrett, who divides his time between southwest France and Amsterdam, and frequently compares them. ‘The rules of a language are also the rules of how you interact with other people,’ he says. ‘Language is more than words. The things you say are not without consequence.’

Living in the Netherlands without a knowledge of the language, says Garrett, is like ‘skirting around the edges’ and ‘never really getting to the core of the thing’. But for non-Dutch speakers both here and abroad, translated works can open a window onto this hidden world.

‘Literary translation, without meaning to, has partly an educational function,’ he says. ‘You’re introducing readers to ways of thinking, ways of seeing things, that they wouldn’t ordinarily be able to get.’ In fact, one of Garrett’s key motivations at the start of his career was to be able to unlock Dutch literature for other foreigners: ‘I thought, wouldn’t it be great if my friends could read this? Because I know they would really love this.’

A new audience

The international appetite for Dutch literature is increasing. ‘The pool of literary translation has grown in response to demand,’ says Garrett, whose sector has roughly tripled in size since he began translating in the 1990s. ‘I have the feeling that, in the last few years, Dutch literary fiction – in some circles – is getting some of the attention that you were seeing Scandinavian detective literature getting maybe ten years back,’ he says, moderating the sentence every few words to avoid overstating anything, like a sculptor honing his work.

The clearest example of the globalisation of Dutch literature is perhaps Garrett’s translation of Het Diner (The Dinner) by Herman Koch – a New York Times bestseller and the most popular Dutch novel ever translated into English.

‘We got to an audience there with a translated book that was being read by people who didn’t read literature in translation before then,’ he says. For readers new to Dutch literature, Koch is a great starting point, says Garrett, who also recommends Tommy Wieringa (especially Joe Speedboat) and Arnon Grunberg.

Koch, in particular, says Garrett, is ‘very palatable’. ‘It’s easy to take in, and before you know it, you’ve eaten too much … and then he puts you on a roller coaster with a full stomach.’ Dutch literature can be incredibly moreish – an issue, perhaps, if you have a work permit and limited time on your hands.

Sam Garrett’s most recent translations include Herman Koch’s ‘The Ditch’, Tommy Wieringa’s ‘The Death of Murat Idrissi’ and Gerard Reve’s ‘Childhood’. He is currently working on ‘Vallen is als Vliegen’ (Falling is Like Flying) by Manon Uphoff.

Thank you for donating to DutchNews.nl.

We could not provide the Dutch News service, and keep it free of charge, without the generous support of our readers. Your donations allow us to report on issues you tell us matter, and provide you with a summary of the most important Dutch news each day.

Make a donation