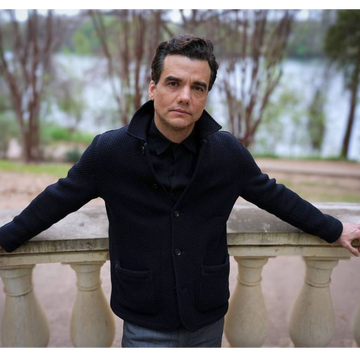

When I made a list of my favorite movies, there were more made by Christopher Nolan than everyone else combined. Memento. Batman Begins. The Prestige. He's a trailblazing director, screenwriter, and producer—one of the rare auteurs of our time. His latest, Dunkirk, is his first film based on a historical event—a dramatic World War II rescue that's told from three perspectives: land, sea, and air.

As an organizational psychologist who studies creativity, a longtime comic-book fan, and a former magician, I was jazzed to dive into the mind behind so many mind-bending films.

Adam Grant: Rumor has it that you don't allow phones on set. Ever. Is it true?

Christopher Nolan: Yes. There's a mass belief that if you're texting, you're somehow not interrupting the conversation—you're not being rude. It's an illusion of multitasking. I started filmmaking when people didn't expect to have a phone on set, when it would've been seen as unprofessional to pull out a phone. Phones have become a huge distraction, and people work much better without them. At first it causes difficulty, but it really allows them to concentrate on what they're doing. Everybody understands. I've had a lot of crews thank me. With a set, we're trying to create a bubble of alternate reality.

My Wharton colleague Nancy Rothbard calls those "task bubbles"—when people are so absorbed in a conversation that they don't even notice what's going on around them. Creativity flourishes in those bubbles, but they're fragile: Other people can burst them.

The person doing it doesn't realize they have taken the energy from the conversation. If you have people in a creative environment where they have to concentrate on what they're doing, you can't have them wandering off in their minds. You can't be texting somebody else and paying attention to what's going on. If you call people on it, they'll repeat the last thing you said. They repeat the words with zero understanding of what they meant. And then over the next minute, you see them start to understand the words for the first time. You can absorb audio information just at the level that you can repeat it back, without understanding.

I've collaborated on some research suggesting that highly creative people procrastinate regularly. What role does procrastination play in your creative process?

I've found that deadlines and pressure actually focus me. I was a great procrastinator, but working in an industrial process where there are deadlines you have to meet—it hasn't hurt my creativity. You have to be realistic about the amount of time you're going to need. I don't fret about what I've done in a particular day as long as I've made progress by the end of the week. It's about not worrying so much about the small elements.

Your films have such clever twists and turns. I sometimes feel that with one more, the audience won't be able to follow the story line. How do you keep us balancing on that tightrope?

You watch a lot of other films, and you see mistakes being made. Like too many reversals—a reversal of a reversal, so what you're creating is flat. I spend a lot of time analyzing my response to other stories. There are masters like Alfred Hitchcock, where there's such an extraordinarily clear control of narrative that's inspiring. It basically teaches you to look for a rule set. You can make up your own, but it has to be internally consistent. I've always had a lot of faith that if the rule set is clear, the audience will come along. Inception is the furthest I've pushed that relationship with the audience. We trusted that if we were diligent and consistent, the audience would trust it. You don't want to feel like a trick was played on you a little too obviously.

The only useful definition of narrative is that it's a controlled release of information. The way in which you release that information is all up to you.

We're notoriously bad at judging our ideas. How do you know when you're onto something?

You do very easily get lost in your own ideas, or your own enthusiasm. As a writer-director, I try to wear different hats. I try to write just as a writer, and then try and read it with some degree of objectivity. Obviously then there are people you trust, but the goal in mind is not total objectivity. What you're really looking for is passion. I'm not an engineer; I'm not building a bridge. When you're crafting a narrative for the cinema, you have to really love it. You have to believe in it as an audience member. I find filmmaking very difficult emotionally. I don't want to moan, because it's the best job in the world, but I do find it difficult. It's very tough to be passionate about something that's already been done. When you know how hard it is to make a large-scale blockbuster, the idea of doing it again in the same way takes a lot out of you. If you make something that you really love, there's going to be something of value.

We've all been encouraged to follow our passion, but if we want to take that advice, we have to find our passion. How have you done that?

I think the thing with passion is that it has to find you rather than you finding it. For me, it's all about trying new things. If you're going to write, you want to read a lot before you write, without any purpose. I love watching TV, love watching movies, preferably with no sense of purpose. Just being open to things that might inspire you—and staying open.

You're saying that creativity is out of your hands. Does that drive you crazy?

It does. But you start to resolve tension. Over time, you stop fretting about there being a right and wrong way to go about it. I'm looking at my desk right now, it's a crazy pile of stuff, but I started to realize years ago that I like having a pile of stuff.

Dunkirk is a new step for you—a film based on a true story. What inspired you to do it?

The seed of the idea is twenty-five years ago, when my wife Emma and myself crossed the Channel on a small yacht with a friend of ours who owned a boat. It was an unbelievably arduous experience . . . and that was with nobody dropping bombs on us. Dunkirk is a story that British people were raised on—it's in our bones. It's a defeat . . . and yet a defeat in which something marvelous happens. It has an almost biblical, primal sequence to it. Needing a miraculous rescue, and getting it. It's a fascinating tale not of individual heroics but communal heroism. The distinguishing feature of Dunkirk is the coming together of a community. It's a little surprising that no one has told the story in modern cinema. As a filmmaker, you're always looking for that gap.

You've come a long way since the early '90s—you once described those years as a "stack of rejection letters." How did you stay motivated?

What I learned very early on, and I'm very grateful for the lesson, is that I could only be making films for the sake of making films. To only engage in telling a story for the process of telling the story, not for the gold star at the end. It's tricky. You grow up in school getting grades on papers, and then you get out into the real world and realize that no one is even going to grade your paper.

You have to cross into this world of just pleasing yourself, just doing something because you want to do it. It was a very valuable lesson. The truth is you have to hang on to your own belief. At the end of the day, all you really have is your own belief, your own passion. You can't ignore the feedback. But you tell the story because you love it.

This article appears in the August '17 issue of Esquire.