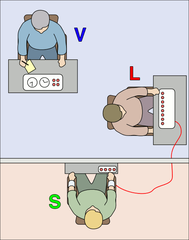

Julie A. Woodzicka (Washington and Lee University) and Marianne LaFrance (Yale) report an experiment reminiscent of Milgram’s famous studies of obedience to authority. Reminiscent both because it highlights the gap between how we imagine we’ll respond under pressure and how we actually do respond, and because it’s hard to imagine an ethics review board allowing it.

Julie A. Woodzicka (Washington and Lee University) and Marianne LaFrance (Yale) report an experiment reminiscent of Milgram’s famous studies of obedience to authority. Reminiscent both because it highlights the gap between how we imagine we’ll respond under pressure and how we actually do respond, and because it’s hard to imagine an ethics review board allowing it.

The study, reported in the Journal of Social Issues in 2001, involved the following (in their own words):

we devised a job interview in which a male interviewer asked female job applicants sexually harassing questions interspersed with more typical questions asked in such contexts.

The three sexually harassing questions were (1) Do you have a boyfriend? (2) Do people find you desirable? and (3) Do you think it is important for women to wear bras to work?

Participants, all women, average age 22, did not know they were in an experiment and were recruited through posters and newspaper adverts for a research assistant position.

The results illuminated what targets of harassment do not do. First, no one refused to answer: Interviewees answered every question irrespective of whether it was harassing or nonharassing. Second, among those asked the harassing questions, few responded with any form of confrontation or repudiation. Nonetheless, the responses revealed a variety of ways that respondents attempted to circumvent the situation posed by harassing questions.

Just as with the Milgram experiment, these results contrast with how participants from a companion study imagined they would respond when the scenario was described to them:

The majority (62%) anticipated that they would either ask the interviewer why he had asked the question or tell him that it was inappropriate. Further, over one quarter of the participants (28%) indicated that they would take more drastic measures by either leaving the interview or rudely confronting the interviewer. Notably, a large number of respondents (68%) indicated that they would refuse to answer at least one of the three harassing questions.

Part of the difference, the researchers argue, is that women imagining the harassing situation over-estimate the anger they will feel. When confronted with actual harassment, fear replaces anger, they claim. Women asked the harassing questions reported significantly higher rates of fear than women asked the merely surprising questions. Coding of facial expressions during the (secretly videoed) interviews revealed that the harassed women also smiled more – fake (non-Duchenne) smiles, presumably aimed at appeasing a harasser that they felt afraid of.

The research report doesn’t indicate what, if any, ethical review process the experiment was subject to.

Obviously it is an important topic, with disturbing and plausible findings. The researchers note that courts have previously interpreted inaction following harassment as indicative of some level of consent. But, despite the real-world relevance, is it a topic that is it important enough to justify employing a man to sexually harass unsuspecting women?

Reference: Woodzicka, J. A., & LaFrance, M. (2001). Real versus imagined gender harassment. Journal of Social Issues, 57(1), 15-30.

Previously: a series of Gender Brain Blogging

Much more previously: an essay I wrote arguing that moral failures are often defined by failures of imagination, not of reason: The Narrative Escape

fake (non-Duchenne smiles), presumably aimed at appeasing a harasser that they felt afraid of.

Fear is kind of an odd term in this case, more like social discomfort in the presence of an authority? Is there not more than one type of non-Duchenne smile? I’d assume their “smile” is more like disbelief or embarrassment. Women want to be known for the same thing men do – their accomplishments. Not for complaining and causing a stir. Sadly, not creating more unwanted attention is often the primary concern.

The researchers asked directly if the participants felt afraid, so it isn’t just an interpretation from the facial coding analysis

Thanks for the clarification! I do wish researchers would offer the questionnaire in the paper so as to view the choices, but I get the general idea. Thank you for covering this topic – very important!

Is it possible the disconnect between the anticipated reaction and actual reaction to harassment was a matter of degree? If the subjects were just asked, “How would you react to being harassed in an interview?” is it possible that when they answered they were thinking of much more severe and blatant actions such as, “Would you consider sleeping with me to get this job?” “Do you have a boyfriend?” is a whole different level/degree of harassment and the reaction may be commensurate.

Not possible in this case – the participants in the “imagined harassment” condition were told, word-for-word, the same harassing questions as were used in the “experienced harassment” condition

It is a shame those ladies wasted their time in an interview they believed might lead to a research position. Hope they were told afterward what they really were doing there, so they never answer ads like that again.

That’s one aspect of the ethics, isn’t it. If they never answer adverts for that kind of job again then these researchers have harmed the community of people who place job adverts hoping for respondents, as well as upsetting the participants

Isn’t there some ethics process where students sign up to participate in experiments and they agree / are warned in advance at some point to be subjected to something stressful? Then much later on something like this (the interview) is set up.

These weren’t students, but, yes, there are ways of asking for people’s consent to be deceived before deceiving them (there’s a nice example in Roger Brown’s “Social Psychology” which I don’t have to hand right now)

An answer why people do not report sexual harrasment comes from this thought experiment which makes it obvious that it is all about power and only partly linked to gender.

Sorry that the link is in German. Look for the expression “Gedankentest” on page 2 and google translate the article starting from there.

http://www.faz.net/aktuell/feuilleton/debatten/warum-rd-14621855.html

I think that research such as this is hugely important, however unsettling. It needs to be done (with proper safeguards and disclosures…) There are often huge gaps between what we say or believe we will do and what we actually do. And such things rarely get challenged. Or rarely deeply studied. (…by ourselves or outsiders…)

Current humans like to pretend we are either clear or simple, when we aren’t. Ironically, we are more and more pretending we are just somewhat advanced robots, while at the same time we are working on getting robots or AI to be more and more sophisticated and even sentient. We truly are at risk of losing or reducing our sentience because we don’t want to deal with the vast complexity, levels, and contradictions that exist within us. We are almost embarrassed by our complexity and want to reduce it while we attempt to give it to AI and machines….

Looking deeply inside our self is becoming less and less popular….