Your boss ominously requests an urgent meeting, your taxi is inching towards the airport with minutes to spare before your flight, or your football team have been granted a potentially game-winning penalty in the 91st minute. Your heart pounds, your stomach lurches, your hands turn clammy: the effects of stress are visceral and instantaneous.

When faced with a perceived threat, the body’s fight or flight system triggers in a well-choreographed sequence that has evolved over millions of years. “We’re here because our ancestors were so brave and could survive through times of terrible stress and threat,” says Carmen Sandi, who leads a behavioural genetics laboratory in Switzerland. “The problem nowadays is that we’re activating this ancient survival response in a job interview.”

In the modern world, where life-threatening situations are encountered rarely, stress itself has become the spectre. Last year, in the largest survey on the impact of stress, three in four Britons reported being so stressed that they had felt overwhelmed or unable to cope at least once over the last year. Studies across populations have linked extreme and chronic stress with heart disease, diabetes and mental health problems including depression. What is it doing to our bodies?

Adrenaline rush

The moment we perceive a threat, the brain’s alarm system, a region called the hypothalamus, issues a series of commands designed to prepare us for fight or flight. Among the first to receive the alarm signal are the adrenal glands, which sit like little hats on top of the kidneys. Within seconds, they begin to pump out adrenaline, causing our heart and breathing to speed up and triggering the release of huge amounts of glucose from our liver.

Blood is shunted away from the digestive system towards our arms and legs and the muscles around our small intestine contract, creating the feeling of a knot or fluttering in our stomach. For reasons that are not entirely understood – possibly the body’s way of trying to remove any harmful toxins – adrenaline loosens the bowel muscles, meaning that acute stress can leave us racing for the bathroom. Another unwelcome side-effect is sweat, which is more sudden and smells worse than the kind produced during exercise or in hot weather. While exercise sweat comes from the eccrine glands and contains mostly water, adrenaline activates the apocrine glands in the armpits, which release a milky-looking substance containing fats and proteins, fuelling bacteria.

Adrenaline also prompts a massive mobilisation of immune cells, which travel from the spleen and bone marrow where they are stored, into the bloodstream. “There’s an evolutionary theory that in the past social stress was often a predictor of trauma or violence,” says Ed Bullmore, a professor of psychiatry at the University of Cambridge, who is exploring the link between stress and the immune system. “When I’m standing up doing a public presentation, my [subconscious] looks at all these people staring at me and says ‘Maybe they’re going to attack’ – so my immune system ramps up in advance.”

While adrenaline floods the body within seconds, a second stress hormone, called cortisol, seeps into the bloodstream more gradually, peaking after 20-30 minutes. Cortisol changes the metabolism of cells, how cells function and alters the activity of DNA. In the brain, cortisol binds to neurons, altering normal thought processes including the way stressful events are recorded in our memories. Neuroscientists think the influence of cortisol could explain why our memories of traumatic or highly emotional events are often exceptionally vivid.

Is stress always bad?

Research suggests that some stress exposure is crucial for developing the resilience that allows us to cope with unexpected and challenging situations in the future. A 2013 review entitled “Understanding resilience” draws parallels with the way exposure to germs boosts the immune system, concluding: “Stress inoculation is a form of immunity against later stressors, much in the same way that vaccines induce immunity against disease.”

Adrian Wells, a professor of clinical and experimental psychopathology at the University of Manchester, agrees. He is concerned that the negative effects of stress are sometimes exaggerated and that an “epidemic of stress phobia” is turning situations that ought to be challenging or even exhilarating into something altogether more traumatic.

“The pursuit of a stress-free life is not healthy,” says Wells. “Stress is like exercise. It’s pretty uncomfortable at the time, but you build stamina and strength.”

This view is backed by recent research showing that the way we think about stress can also determine its effects. In one study, a group of volunteers were given a series of anxiety-inducing tasks: singing karaoke (sober, in a laboratory setting), giving a speech and completing a difficult maths problem. Participants were split into three groups, who were instructed to say “I am excited”, “I am calm” or “I am anxious” before each task. Those who reframed their stress as excitement performed significantly better on all the tasks. For someone weighing up whether to apply for a job or take part in a race, say, the findings are an encouraging reminder that risks can open up rewarding opportunities. But it may not help with many other sources of stress – facing discrimination at work or caring for a parent with Alzheimer’s, for example.

Can burn out make you ill?

There is growing evidence that when stress is extreme or unrelenting the health consequences can be significant. Stress increases blood pressure and temporarily makes the blood stickier and more likely to clot, meaning that, over prolonged periods, it can raise the risk of heart disease.

Scientists are also investigating the link between stress and type 2 diabetes. The possibility of a link has been speculated about for centuries, with the 17th-century English physician, Thomas Willis, attributing the condition to “sadness, long sorrow … and disorders of the animal spirits”. Recent studies have confirmed the connection; Japanese men working excessive overtime were more likely to become diabetic, for instance. However, it it not yet clear whether stress itself, or other lifestyle factors such as diet, lack of exercise and drinking alcohol, are to blame.Under normal circumstances, the stress response is designed to be self-limiting: a momentary surge of biological activity that quickly dissipates. This relies on a precisely choreographed sequence of hormone levels rising and falling by the right amount in the right order. Adrenaline triggers the release of immune cells, while cortisol, which lags behind, dampens down immune activity, bringing the body back to baseline. When people are relentlessly exposed to stress, though, this complex and finely balanced sequence can start to go awry.

One study, involving teachers who were either happy with their job or “burnt out”, found that the burnt out group had higher levels of inflammation, a sign that the immune system is being placed under strain. Similar findings have been made in people who are long-term caregivers and in those who had suffered serious trauma as children.

Bullmore believes that stress may leave an imprint on the immune system comparable to that left by an infectious disease, something he calls the “inflammatory memory of stress”. The theory is intriguing as it ties in with the recent discovery that inflammation in the body can have negative effects on mental health. It also challenges the traditional belief that the brain is sealed off from the rest of the body by what is known as the blood-brain barrier. Increasingly, scientists are showing links between mental and physical health. “The biggest single risk factor for depression is stress,” says Bullmore. Understanding better this connection could open up new opportunities for treatments targeting immune activity and could even make it possible to intervene before depression occurs in people at risk.

It’s personal

Scientists are also discovering that not everyone responds to stress in the same way. Sex hormones interact with stress hormones, which could explain why stress appears to manifest itself differently in men and women. Scientists at Rockefeller University in New York found that after prolonged stress, the brains of male and female rats began to rewire in subtly different ways. In female animals, neurons in the prefrontal cortex, the brain’s control centre, grew more connections to the amygdala, a brain region linked to emotion. However, in the male animals these connections did not change, while links to other brain areas became less functional.

Scientists are still trying to work out how such changes in brain circuitry affect how we feel and behave. Men are more likely to take it out through antisocial behaviour such as substance abuse whereas women are more likely to have a depressive episode,” says Bruce McEwan, a professor of neuroendocrinology at Rockefeller who led the experiment in rats.

A person’s genetic makeup also helps explain why some of us thrive on stress while for others it can be the trigger for a devastating mental illness. Natalie Matosin, a neuroscientist at the University of Wollongong, Australia, is investigating the cumulative effects of stress over a lifetime, based on physical and chemical clues left behind in brain tissue. She examines slivers of postmortem brain samples under the microscope, comparing the brains of healthy donors with those of people who were diagnosed with PTSD or depression. “I’ll look at how the quantity, shape of brain cells have changed,” she says. “Other times I’ll get just a couple of granules of tissue and look at the composition of proteins that make it up.”

One of the most startling discoveries focused on a gene called FKBP5, that is activated by circulating cortisol. Matosin and colleagues discovered that in people carrying a certain variant of this gene, the gene was switched on far more readily, amplifying the effect of cortisol as it courses through the body. “If you express too much of the gene it’s bad because it means you can’t switch off the stress response,” she says. “If you can’t switch off the stress response over an extended period of time, it can have an impact on the way your brain functions.”

People who carry the risk gene tend to have higher levels of cortisol and are also more likely to develop a psychiatric disorder after being exposed to very stressful circumstances. Like others in the field, Matosin hopes that it will one day be possible to identify those who are most vulnerable to stress and provide more effective treatments. “There are so many reasons that can cause psychiatric disorders and part of the reason we don’t have good treatments for them is that at the moment we’re just guessing,” says Matosin.

Stress is unavoidable and according to scientists the quest for a stress-free existence is likely to be futile. However, an emerging scientific understanding of stress could in future help protect us from its very darkest side.

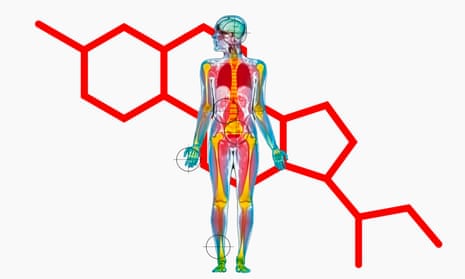

Meet the hormones – what happens during the fight-or-flight response?

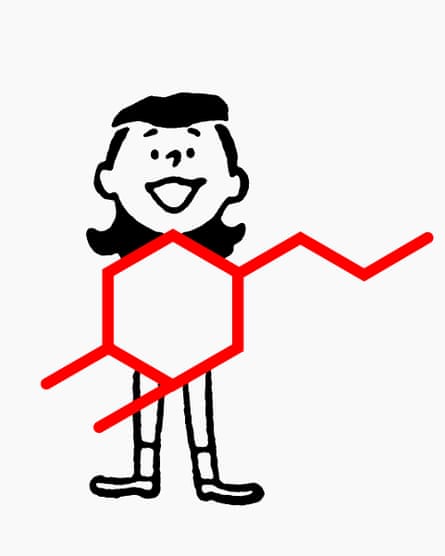

Cortisol: Formula: C21H30O5

Surges during times of stress, helping to increase the body’s metabolism of glucose, control blood pressure and reduce inflammation. After a stressful experience, levels should reduce. However, when people are continually under stress, the body’s balance can be derailed. Continually high levels have been linked to anxiety and depression. On the upside, light exercise and even laughter have been shown to reduce cortisol.

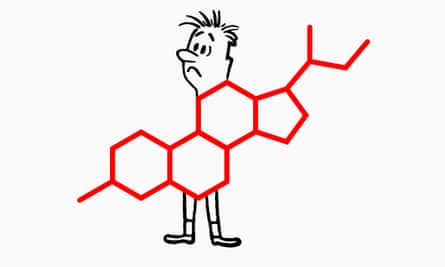

Adrenaline: Formula: C9H13NO3

Causes the heart to start pumping rapidly and air passages to dilate (providing muscles with oxygen). It also reduces the body’s ability to feel pain, which is why people can be oblivious to an injury until after danger has passed. But if levels are continually elevated, studies suggest this could become detrimental, particularly to cardiac health.

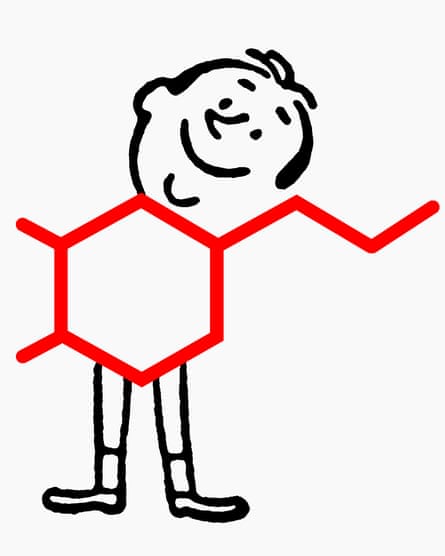

Noradrenaline: Formula: C8H11NO3

Chemically very similar to adrenaline, and does much of the same job but with more of an influence on blood pressure. Levels in the body follow a circadian cycle, being lowest during sleep and rising in the morning. During stressful situations, it acts in the brain to make us feel more alert and to enhance our ability to form memories.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion